What does ‘Wales and the Sea’ mean to me?

Well, quite simply, it’s a huge part of who I am!

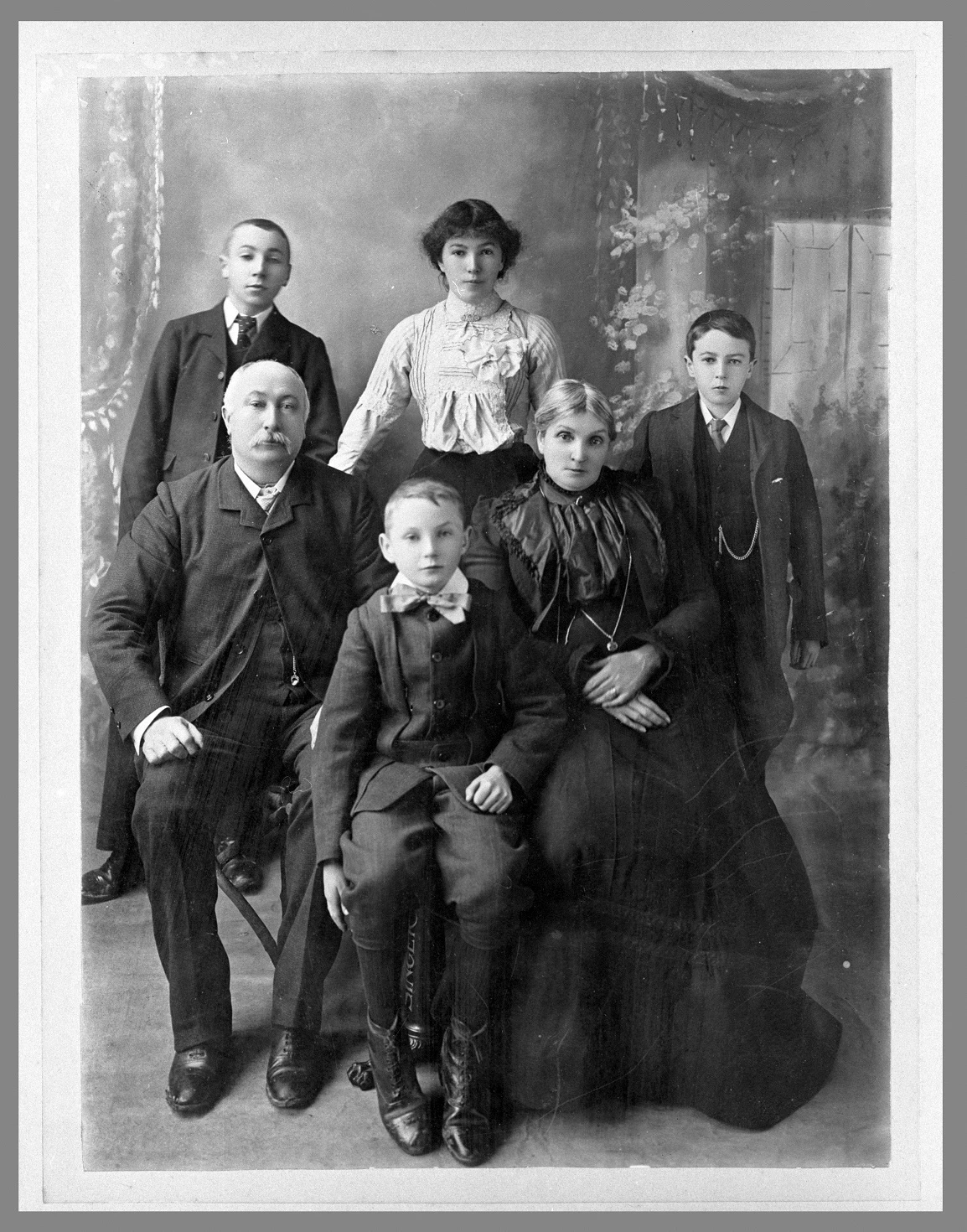

Through my late father, I am the nephew, grandson, great nephew, great-grandson and great-great grandson of seafarers from the Ceredigion coastal village of Aber-porth.

They were all part of the massive, disproportionate even, contribution that Welsh seafarers made to the British merchant fleet during the two centuries 1750-1950.

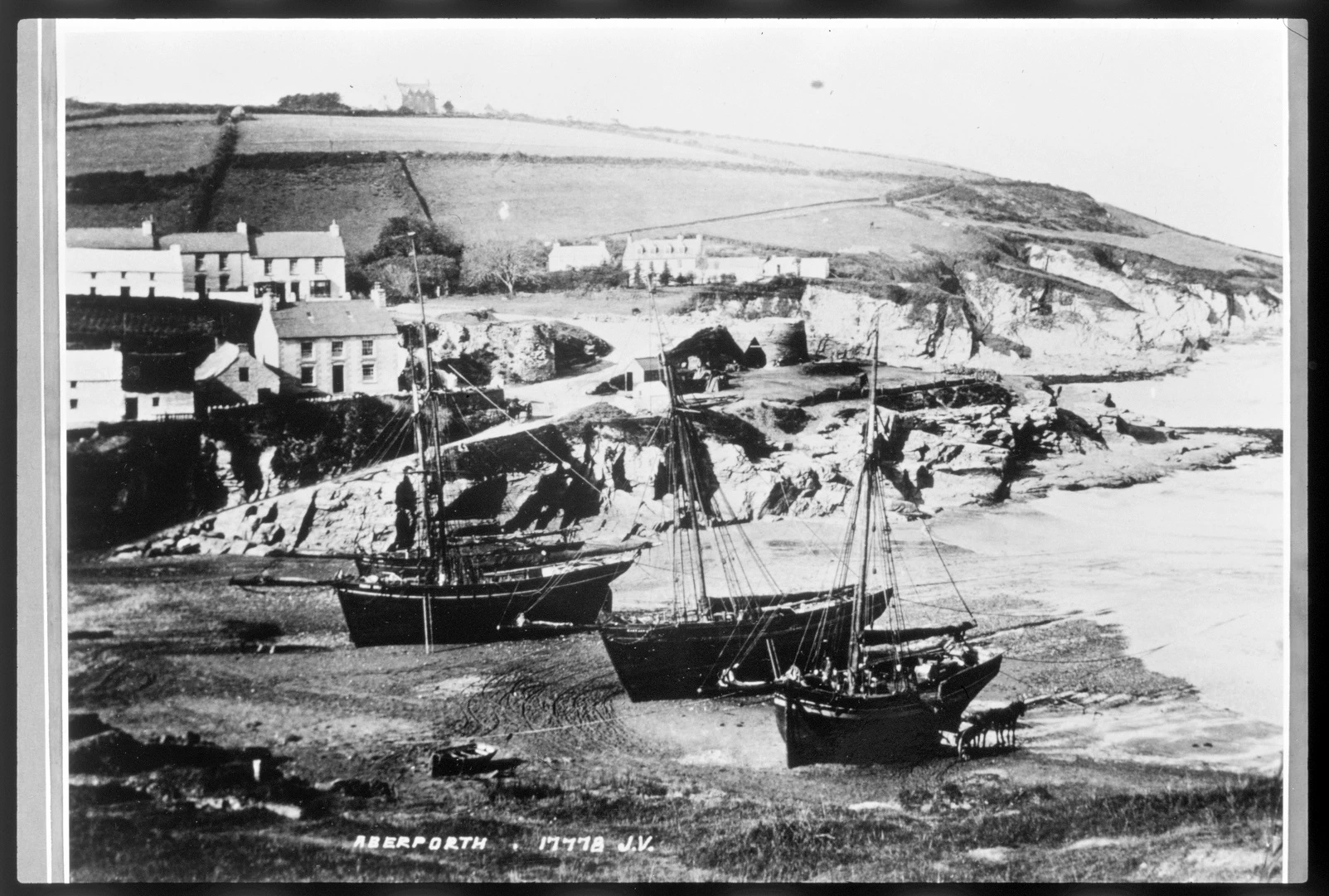

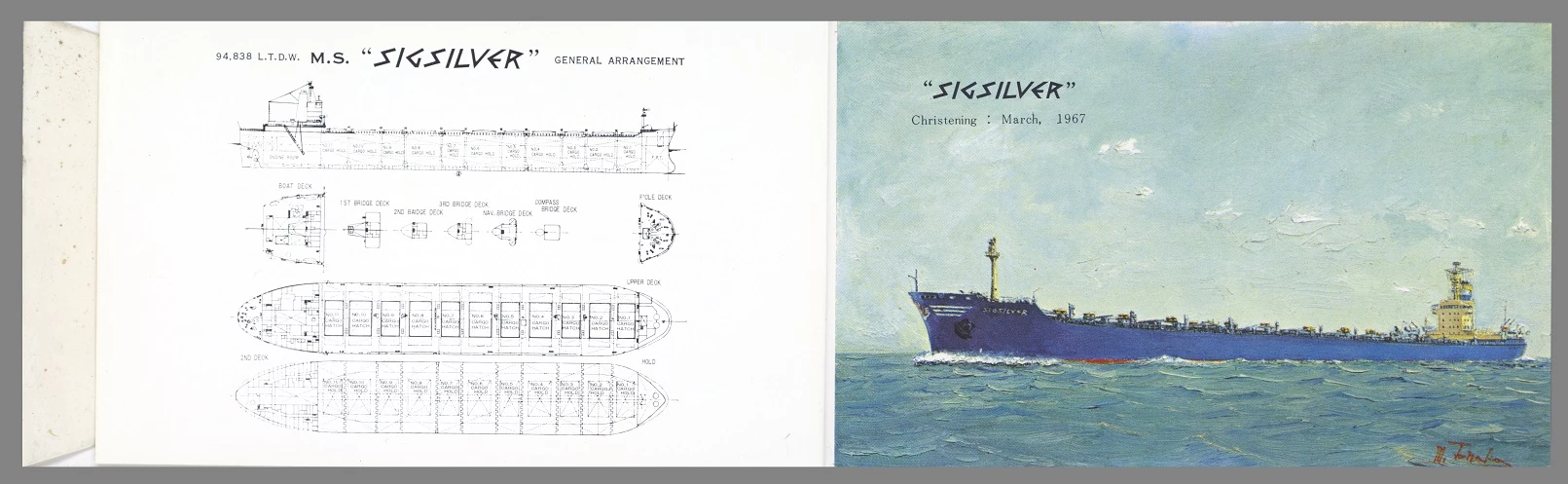

Almost all reached the rank of master mariner, and over the centuries they commanded vessels that ranged in size from little coastal smacks that brought culm and limestone to Aber-porth in the 19th century, to the largest bulk carrier under the Red Ensign in the late 1960s.

One of them lies deep in the cold waters off Newfoundland where he drowned after his ship struck an iceberg. Another lies buried in the British cemetery at Chacarita in Buenos Aires, where he died whilst the Cardiff tramp he commanded was discharging Welsh coal to power Argentina’s railways and meat packing plants. Another had to deal with a murder on his ship after a dispute between two crew members over a gambling debt got way out of hand.

But mine is just not a story about seafaring men.

Communities like Aber-porth, where, at any one time in the early 20th century, up to half the village’s male population might be away at sea, were matriarchal communities, where strong women brought up families single-handed and endured the absence of their loved ones over extended periods. It is difficult to fathom the anguish and worry that they must have experienced on countless stormy nights, with thousands of miles of forbidding seas between them and their loved ones.

Nevertheless, there were advantages to being a captain’s wife! If their husband’s ship was in an UK or near-continental port, they would often travel to meet them for a brief interlude of conjugal company, taking advantage of their visits to sample the best shops with the latest fashions in Cardiff, Newcastle or Glasgow - even Antwerp or Hamburg!

And the wives of master mariners were always accorded the respect ashore that their husbands had at sea – my great-grandmother would always have been addressed as Mrs. Captain Jenkins!

With such an ancestry as this, it is ironic that accidents of employment meant that I was brought up miles from the sea in the heart of Montgomeryshire; visits to relatives in Aber-porth, when we fished for mackerel and set lobster pots, were confined to school holidays!

Montgomeryshire is my mother’s ancestral home; members of her family have been farming in the north of the former county since Elizabethan times at least, and one might think that the sea had little impact on their daily lives.

Nevertheless, in the mid-1880s, they had to leave their home, Ty Ucha' in the village of Llanwddyn, because the River Efyrnwy was being dammed to provide water for Liverpool, then at the height of its commercial success as one of Britain's foremost ports.

The impact of the sea extends far beyond our coasts, so this year’s event should be an event for all of Wales, not just our coastal communities.

Dr David Jenkins, Honorary Research Fellow.