On 15 March we launch our new LGBTQ+ tours at National Museum Cardiff. The tours have been developed in partnership with Pride Cymru working with self-confessed Museum queerator Dan Vo and an amazing team of volunteers.

You may already have read Norena Shopland's blog about the Ladies of Llangollen, and Young Heritage Leader Jake’s post, Queer Snakes! There are so many more LGBTQ+ stories in our collection – stories that have been hidden in dusty museum closets for too long. Friends, it’s time for us to let them out!

To whet your appetite, here’s a quick glimpse at one of the works you might spot on the tour…

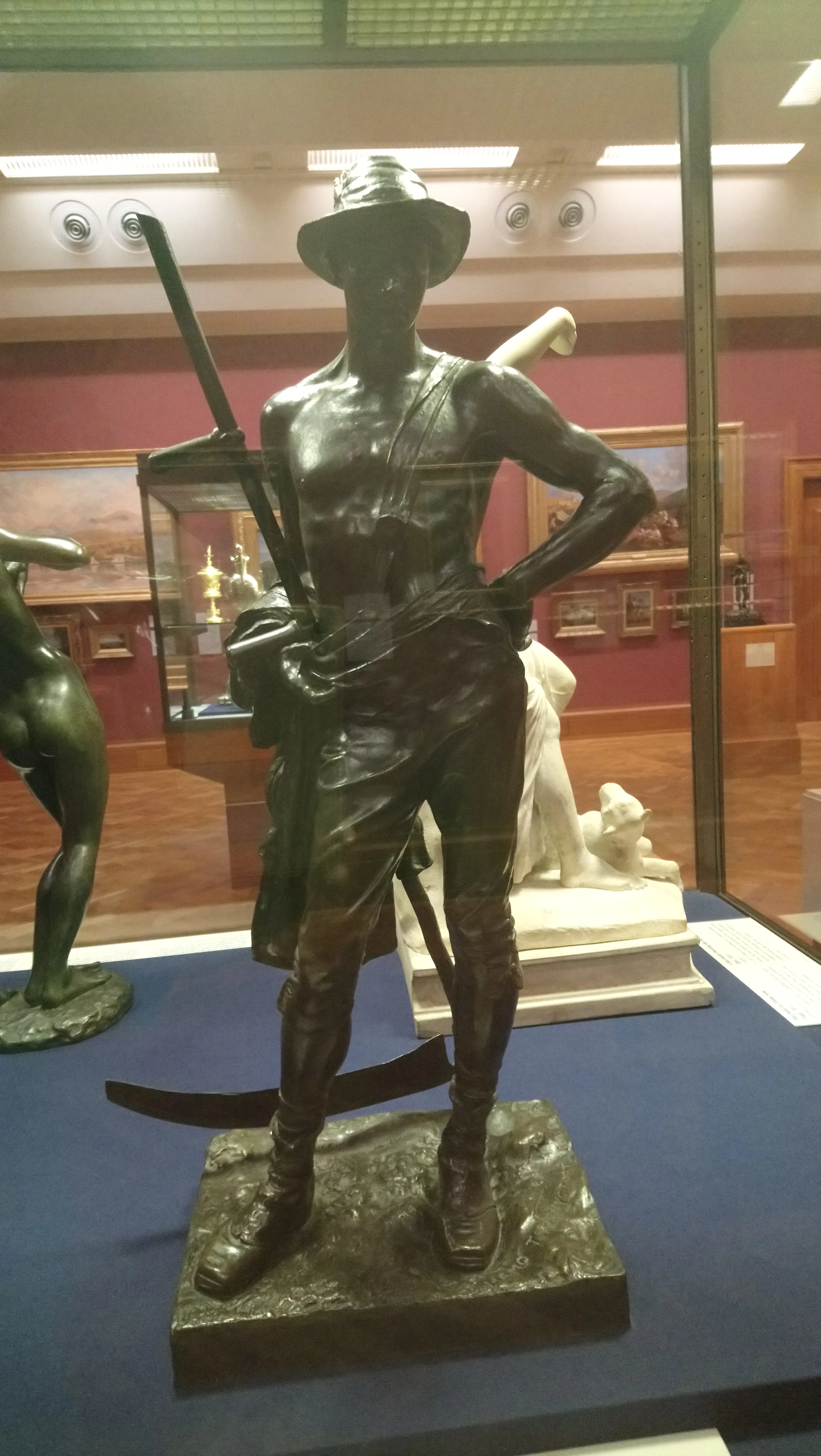

The Mower, by Sir William Hamo Thornycoft

The Mower is a bronze statuette on display in our Victorian Art gallery. It is about half a metre high and shows a topless young farmworker in a hat and navvy boots resting with his arm on his hip, holding a scythe. This sassy pose, known as contrapposto, was inspired by Donatello’s David - a work with its own queer story to tell.

The Mower was made by William Hamo Thornycroft, one of the most famous sculptors in Britain in the nineteenth century, and was given to the Museum in 1928 by Sir William Goscombe John. An earlier, life-size version is at the Walker Art Gallery, Liverpool and is said to be the first significant free-standing sculpture showing a manual labourer made in Britain.

Thornycroft became fascinated with manual labourers and the working classes after being introduced to socialist ideas by his wife, Agatha Cox. He wrote ‘Every workman’s face I meet in the street interests me, and I feel sympathy with the hard-handed toilers & not with the lazy do nothing selfish ‘upper-ten.’ In The Mower, he presents the body of a young working-class man as though it's a classical hero or god – a brave move for the time.

Queering the Mower

With the rising interest in queer theory, many art historians have drawn attention to the queer in this sculpture. In an article by Michael Hatt the work is described as homoerotic, which he describes as that ambiguous space between the homosocial and homosexual.

One of the main factors is the artist’s relationship with Edmund Gosse, a writer and critic who helped establish Thornycroft’s reputation in the art world. Gosse was married with children, but his letters to Thornycroft give us a touching insight into their relationship.

He describes times they spent together basking in the sun in meadows and swimming naked in rivers; and they are filled with love poems and giddy declarations of affection. ‘Nature, the clouds, the grass, everything takes on new freshness and brightness now I have you to share the world with,’ he wrote. Gosse was so obsessed with Thornycroft that writer Lytton Strachey famously joked he wasn’t homosexual, but Hamo-sexual.

Gosse and Thornycroft were spending time together when the first inspiration for The Mower hit. They were sailing with a group of friends up the Thames when they spotted a real-life mower on the riverbank, resting. Thornycroft made a quick sketch, and the idea for the sculpture was born. A wax model sketch from 1882 is at the Tate.

The real-life mower they saw was wearing a shirt, but for his sculpture Thornycroft stripped him down. He explained to his wife that he wanted to ‘keep his hat on and carry his shirt’ and that a brace over his shoulder will help ‘take off the nude look’.

Brace or no brace, it’s difficult to hide the fact that this is a celebration of the male body designed for erotic appeal. Thornycroft used an Italian model, Orazio Cervi. Cervi was famous in Victorian Britain for his ‘perfectly proportioned physique’ (art historical speak for a hot bod!)

Later in the century, photographs of The Mower and other artworks were collected and exchanged in secret along with photographs of real life nudes, by a network of men mostly in London – a kind of queer subculture, although it wouldn’t have been understood in those terms back then.

This was dangerous ground. The second half of the nineteenth century saw what has been described as a ‘homosexual panic’, with rising anxieties around gender identity, sexuality and same-sex desire. Fanny and Stella, the artist Simeon Solomon and Oscar Wilde were among many who were hounded and publicly prosecuted for ‘indecent’ behaviour.

These tensions showed up in the art world too. Many of the artists associated with the Aesthetic and Decadent movements in particular were under scrutiny for producing works that were described as ‘effeminate’, ‘degenerate’ or ‘decadent’. But works like The Mower suggest that art might have provided a safer space for playing out private desires in a public arena at this time.

Book your place on our free volunteer-led LGBTQ+ tours here, and keep an eye on our website and social media for future dates!