Streic, Rhyfel, Corwynt - a'r Brenin yn Dowlais

, 15 November 2016

Archwilio Achau Emlyn Davies y Draper

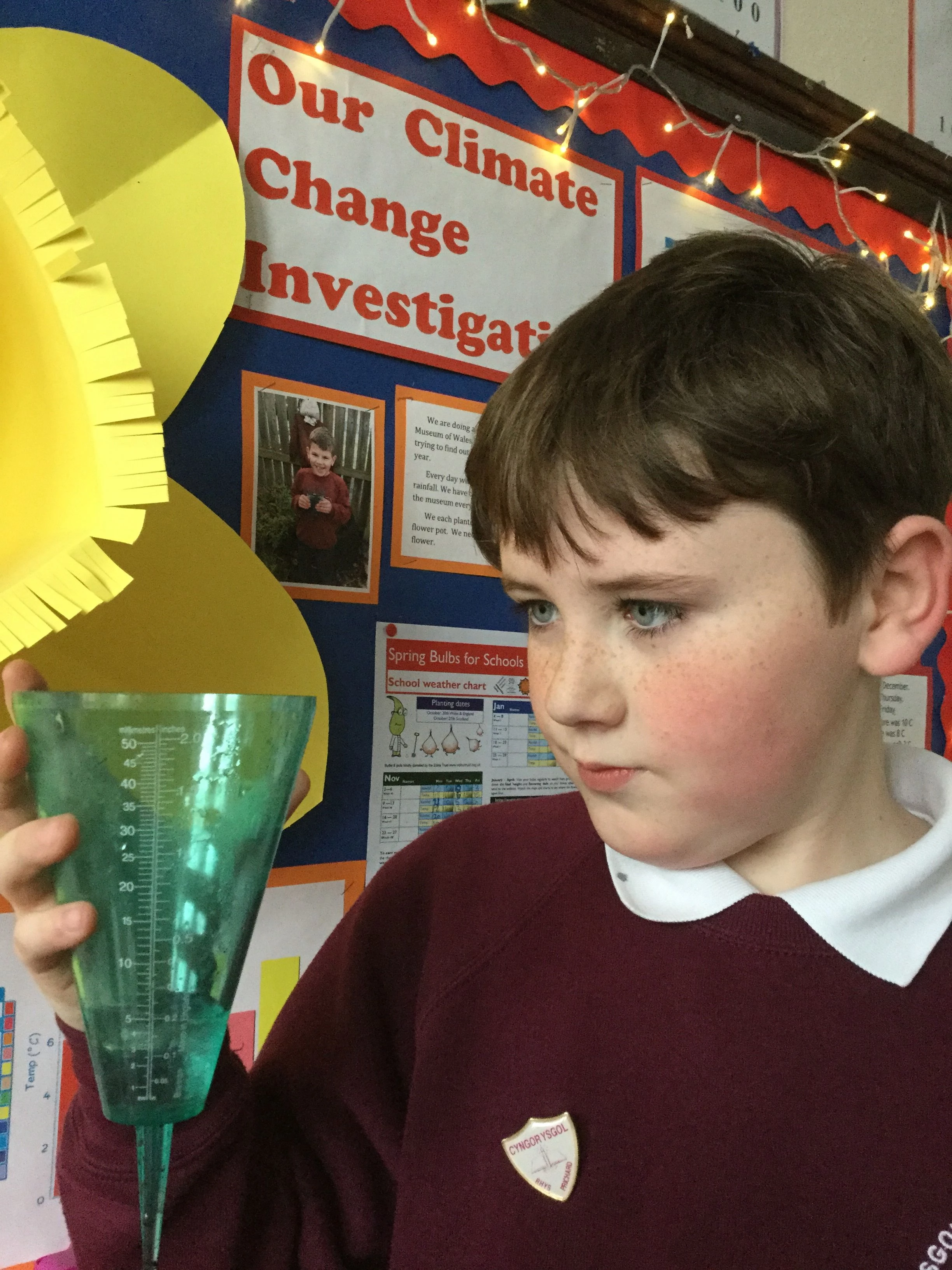

Mae'r gwaith o ddatblygu sesiwn i blant am Siop Draper Emlyn Davies yn parhau yma yn yr Amgueddfa Wlân.

Roedd modd dechrau creu llun cyffrous o’r siop a’i pherchennog trwy bori trwy dudalennau bywgraffiad Alan Owen: Emlyn Davies The Life & Times Of A Dowlais Draper in the first Half Of The Twentieth Century.

I ddechrau, roedd gan Richard Davies (sef enw genedigol Emlyn Davies) linach deuluol drawiadol. Roedd yn perthyn i'r Parchedig John Williams, a oedd yn bregethwr, bardd, cyfansoddwr emynau ac ysgrifwr nodedig; a John Havard a fu’n lawfeddyg ym mrwydr Waterloo.

Ar droad y ganrif ddiwethaf mae’n debyg fod y teulu yn gerddorol tu hwnt, ac yn un o’r rhai cyntaf yn yr ardal i fod yn berchen ar ‘phonograph’, sef dyfais fecanyddol i recordio sain. Mae’n debyg y deuai cymdogion a pherthnasau i fewn yn slei i gyntedd ei cartref i wrando arno!

Blynyddoedd o Eithafion

Bu 1912 i 1914 yn flynyddoedd o eithafion i’r siop a’r ardal:

1912: Bu streic chwerw yn y gweithfeydd rhwng Mawrth 1af a diwedd Ebrill a gafodd effaith ddifrifol ar fusnesau lleol. Yna i’r gwrthwyneb yn llwyr fe siriolwyd Dowlais ddigysur gan faneri ac addurniadau lliwgar ar Fehefin 29fed pan ymwelodd y Brenin a’r Frenhines â’r dre.

Hydref 1913: Bu trychineb gwaethaf y diwydiant glo yn yr ardal sef Tanchwa Senghennydd, lle cafodd 439 o ddynion a bechgyn eu lladd.

Y stori fwya hynod ac annisgwyl efallai oedd cysylltiad y siop a storm ddifrifol a ddigwyddodd bythefnos ar ôl y digwyddiad ofnadwy hwnnw. Bu corwynt enfawr a chwythwyd a chlwyfwyd Doli - un o geffylau cludo parseli y siop, drosodd yn y gwynt!

1914: Ac ar nodyn ddwysach fyth - yr Ergyd Farwol - Y Rhyfel Byd Cyntaf a’i holl erchylltra a gyffyrddodd â phob cymuned.

Rhyfeloedd Byd: Newid Byd yn Nowlais

Bu byd o newid i nifer o bobl wedi‘r rhyfel byd 1af, ac yn enwedig i ferched. Mae Miriam - Minnie fel y gelwid - merch hynaf Emlyn Davies, yn esiampl o’r effaith yma.

Yn ystod y rhyfel er ei bod hi’n astudio mewn ysgol breswyl yn Aberhonddu, fe ddychwelodd i helpu yn y siop oherwydd bod nifer o’r dynion wedi gorfod mynd i ymladd. Yna, yn 1937 wedi marwolaeth ei thad, etifeddodd y siop mewn cyfnod anodd a thywyll arall.

Fe wnaeth y rhan yma o’r stori a’i chymeriad a’i bywyd hi gynnig ei hun fel spardun i greu sesiwn ysgolion yma yn yr Amgueddfa Wlân.

O fantais hefyd oedd bod hwn yn hanes o fewn côf. Cyffrowyd fi wrth feddwl mod i’n mynd i gael cyfle i wrando ar Mr Owen yn darlunio’r siop yn ystod y cyfnod cythryblus yma.

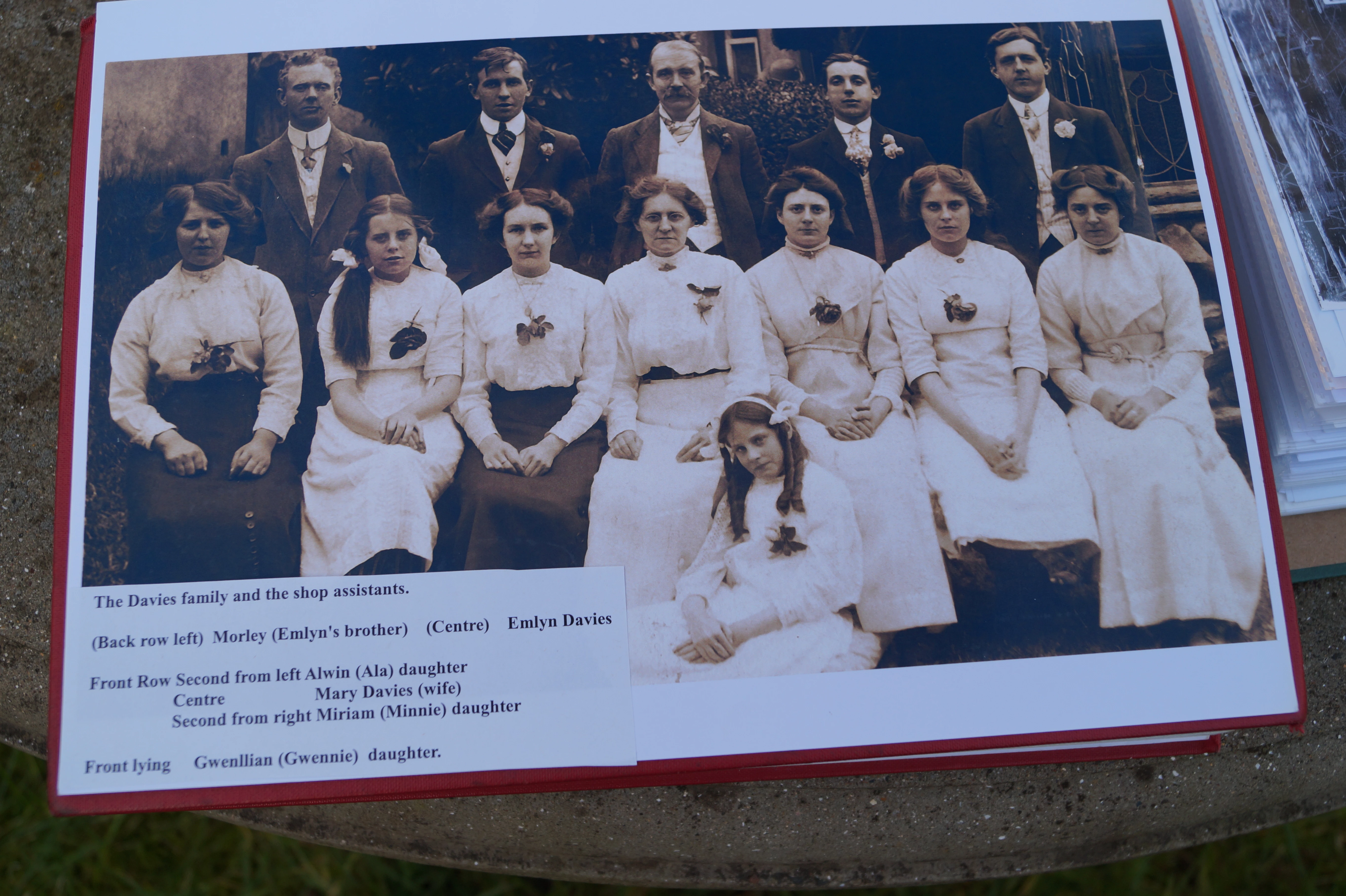

Cwrdd â Theulu Emlyn Davies

Dyna od fel mae rhywun yn dechrau tueddu dychmygu bod cymeriad mewn ffilm, llun neu lyfr yn parhau i fod yr un oed am byth - ac wrth deithio gyda'r curadur Mark Lucas i fwthyn bach ar gyrion Castell Newydd Emlyn i gyfarfod a Alan Owen (wyr Emlyn Davies), bron i mi argyhoeddi fy hun fy mod yn mynd i weld bachgen bach gyda chapan a throwsus byr a la y 30au!

Yr hyn sydd yn arbennig am gael cyfarfod wyneb yn wyneb a phobl sydd ynghlwm â hanes fel hyn yw eich bod yn cael gwell amgyffred o bersonoliaethau. Cofiai Mr Owen ei dadcu fel person hoffus, cariadus, a charedig - ac er ei fod yn amlwg yn ddyn busnes llwyddiannus gyda chyfrifoldebau mawr yn ei waith a’i gymdeithas, roedd hi’n ddifyr i ddarganfod y berthynas a fu rhyngddynt.

Cofiai fel y deuai ei dadcu ag anrhegion yn ôl iddo fe a’i chwaer bob tro y teithiai ar hyd y wlad ar fusnes. Cofiai gael llwnc o gwrw ganddo hefyd a chael ei gwrsio rownd y cownter!

Soniodd llawer am y gymuned fel yr oedd yn blentyn - roedd llawer o Wyddelod yn byw yn yr ardal yr adeg honno ac roedd atgofion ganddo am orymdeithiau lliwgar ‘Corpus Christi’yn Dowlais.

Bu Mr Owen a’i chwaer ‘fach’ Mrs .Joan Preston (trwy ebost) yn garedig tu hwnt yn rhannu nifer o’u hatgofion o’r siop yn ystod y rhyfel pan fu eu mham Miriam Owen (Minnie) yn rhedeg y siop – ond eto mwy am hyn yn y blog nesaf!

Y gamp nesaf fydd cwtogi yn ofalus hanes hanner cant o flynyddoedd y siop i script 45 munud!