Happy Pride Month!

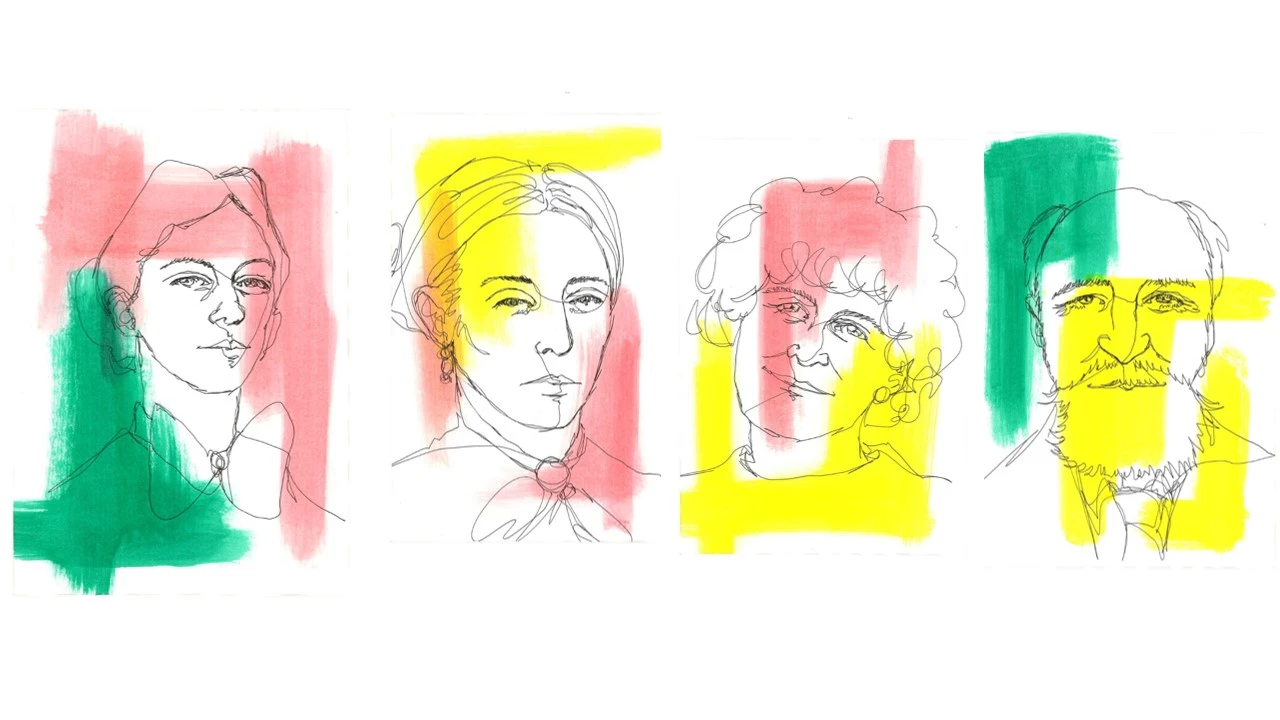

We've got an introduction to 4 prominent LGBT-people from Welsh history for you.

This text was written by Young Heritage Leaders during last LGBTQ+ History Month; thank you to Norena Shopland for helping with our research and diolch to The National Lottery Heritage Fund for their "Kick the Dust" support of our work with Young People.

This blog was written as part of our Hands on Heritage project.

Words by Holly

Images by Cecile

Gwen John

‘I should like to go and live somewhere where I meet nobody I know till I am so strong that people and things could not effect me beyond reason.’

Gwen was born on 22 June 1876 in Haverfordwest to Edward and Augusta John. Growing up, she had one older brother, a younger sister and a younger brother, the artist Augustus John. When their mother died young the family moved to Tenby, where Gwen’s education was placed in the hands of governesses. Her childhood years seemingly left little impression; she later said that nothing important happened to her before she turned 27.

Gwen is well-known for her affair with the sculptor Auguste Rodin, but she had sexual relationships with both men and women over the course of her life. Whilst attending he Slade School of Fine Art in London in the 1890s, she developed passionate feelings for an unknown woman, who ended up disposing herself of Gwen’s affections when she began a relationship with another man. Gwen threatened suicide if she did not break it off. This man eventually returned to his wife, but the love between Gwen the object of her passion had turned to hate.

In 1898 Gwen travelled with a group of friends to what was at the time the centre of artistic culture in the Western World: Paris. This period was a big influence on her art, at the end of which she painted her first self-portrait.

Throughout her life she challenged and defied convention. In 1902 she and a friend, Dorelia McNeil decided to walk to Rome to study there. They slept rough on the streets, and sang and painted in return for meals. If this seems daring now, at a time when women were usually chaperoned everywhere by older relatives it would have been totally unheard of. Gwen was also known for her intense focus on her work. She abhorred distractions and often preferred to work alone in her room, when she would become so absorbed she would forget to eat and rest. All this has contributed to Gwen’s reputation as being a bit of a loner, a hermit. Her surviving letters actually reveal that she enjoyed company, although it is difficult to escape the impression that, had Gwen lived today, she may have been diagnosed as having Asperger’s Syndrome, or something like it.

Gwen met Rodin whilst in Paris again in 1904, and began an affair that lasted some 14 years. During this time, Gwen wrote around 2000 letters to Rodin, would organise her days around his visits, and would sometimes stand outside his house watching for him. Rodin frequently explored female sexuality in his work, and sketched Gwen with one of his assistants in erotic poses. Whilst Gwen was intrigued, she later told Rodin it was insignificant compared to being with him.

In later life Gwen converted to Catholicism. She also fell in love for the last time with an older woman called Véra Oumançoff, who became increasingly irritated with her obsessive attentions and was horrified by her sketching during Mass. In her last years she became increasingly isolated, and in 1939 left Paris carrying her will and burial instructions. When she died she was buried in an unmarked grave, and it was not until over sixty years later, thanks to a 2015 TV documentary, that the final resting place of one of Wales’ greatest ever female artists was discovered.

‘It is difficult to express oneself in words for painters, isn’t it?’

Sarah Jane Rees//Cranogwen

‘It is a pretence in everybody, men and women alike, to try to be what they are not; and it is a loss for anybody not to be what they are.’

Sarah was born on 9th January 1839 in Llangrannog, Cardiganshire, the town from which she would later take inspiration for her bardic name. In her later autobiographical writings, she claims the birth of a girl was ‘much awaited for’ after two sons, and she was named after her paternal grandmother who lived with them. At 15 years old, Sarah started going her father out at sea. This was not in itself unusual for the time, but Sarah went on to attend schools in New Quay, Cardigan and eventually London, from which she returned with her Master’s Certificate in Navigation, allowing her to captain a vessel anywhere in the world if she chose.

It was at the 1865 Eisteddford that Sarah was catapulted into the limelight, winning a major prize in the ‘song’ category for her poem ‘The Wedding Ring’. It depicts four working class wives reflecting on their marriages, and placed above other established male writers who were ‘disgusted,’ according to the local newspaper. This was just the beginning of her Eisteddford success, winning a prize at Chester the following year and taking the Bardic Chair (the first woman to do so) at the local Aberayron in 1873. It was around this time that Sarah suffered a great personal tragedy. Fanny Rees was a milliner’s daughter who, like Sarah, had published literary works and moved to London for her education. It was there that she had contracted Tuberculosis, and in 1874 she returned to Wales. It was not to her family home she went to, but that of Sarah, in whose arms she died, something that indicates ‘a requited affection stronger than friendship’ according to Sarah’s biographer. Sarah had clearly loved this woman deeply; it was 12 years before she could bring herself to go to Fanny’s grave to lay flowers.

The success of her writing enabled Sarah to leave her teaching profession. She published a book of poems under her bardic name Cranogwen, which she dedicated to her mother, and became the editor of the Welsh language women’s journal Y Frythones. She often used this position to give advice to her readers regarding marriage and the role of women, and tirelessly promoted women’s writing and education. When two women from Dolgellau asked her advice regarding the suitability of female preachers, Sarah replied in a typically firm fashion: ‘Everyone should preach the Gospel who feels a desire to do so, and can do so, and can get people to listen.’ Her life had never been defined by traditional gender roles, so she would be unlikely to give any other response. At this time, and indeed for most of life, she had been in a happy same sex relationship with Jane Thomas, to whom she addressed one of her most famous poems, ‘My Friend’: ‘I love you, my beloved Venus, my Ogwen.’ At the time Ogwen was the female subject of a popular love ballad. Sarah clearly puts herself in the role of the male lover, leaving no doubts about the nature of their relationship.

Despite her sexuality, Sarah was a committed Christian, seeing human love as being ‘beamed from the warmth of the divine breast.’ She was a frequent preacher, though she was often relegated to using the deacon’s pew due to her gender, and at 60 years old founded the South Wales Women’s Temperance Union, which by the time of her death had 140 branches across Wales. She died in 1916, aged 81. The Union set up a shelter for homeless women and girls in her memory in 1922, in recognition of her unending efforts to improve the lives of Welsh women.

‘Gender difference is nothing in the world.’

Jan Morris

‘I was three or perhaps four years old when I realised I have been born into the wrong body, and should really be a girl…it is the earliest moment of my life.’

Jan was born James Humphrey Morris to a Welsh father and an English mother in Clevedon, Somerset, on 2nd October 1926. She was aware of being transgender from an early age, and remembers as a child at Catherine Choir School in Oxford praying to God to make her a girl. After graduating from Oxford University, she had a brief career as a soldier in the closing months of the Second World War. She became a well-known journalist, built on the back of breaking the news of Hillary and Norgay’s successful ascent of Everest on the day of the Queen’s coronation. When reporting on the Suez Crisis, she provided the first irrefutable proof of collusion between France and Israel in invading Egyptian territory.

But the feeling of being born into the wrong body remained. Whilst still living as James she had married; her wife Elizabeth knew from the beginning that she was transgender and has been a lifelong support. They went on to have five children, one of whom died in infancy. With her wife by her side, Jan began taking steps towards gender reassignment, though many tried to convince her that she needed to be cured, or that she was really homosexual. Having been referred to Charing Cross, she was told that she and Elizabeth would have to get divorced. Jan adamantly refused. Eventually, in 1972 in Morocco, ‘James’ underwent surgery and officially became Jan Morris. Two years later her landmark book Conundrum was published, one of the first autobiographies to discuss transgender issues and gender reassignment.

Whilst she acknowledges that the question of her gender overshadowed her work at first, she has gone on to write around 46 books, including the Pax Britannica trilogy. She does not see her surgery as having changed her writing, in fact, ‘it changed me far less than I thought it had.’ In the past, other feminists have criticised her for simplifying traits associated with gender, something she acknowledges, and now says her views have matured. In 2008 she and Elizabeth entered into a civil partnership in Pwllheli, close to where they now live.

Morris has now fully adopted Wales, or perhaps Wales has adopted her. After moving to Wales, she was adopted into the Gorsedd of Bards in 1993, which she sees as one of the proudest moments of her life. She considers herself a Welsh nationalist, although she accepted a CBE in 1999 out of respect. Her picture of Wales sometimes seems to border on the romanticised, the fantastical. Just before her reassignment surgery she spent the summer in North Wales, and would often visit a secluded lake: ‘There I would take my clothes off, and stand for a moment like a figure of mythology…I fell into the pool’s embrace, [and] sometimes I thought the fable might well end there, as it would in the best Welsh fairy tales.’

Jan now rarely speaks about being transgender and does not join with LGBT activism, preferring to be seen first and foremost as a writer. Last year, at the age of 91, she published another book, Battleship Yamato. She has also written a book of allegories, to be published after her death.

“Looking back on my life, of course I had this feeling that I was in the wrong sex and I had to get out of it. But it didn’t occur to me then that the ultimate object might be to be both. And the next object is to be neither.”

Angus McBean

“Kings and queens, princesses sleeping or otherwise in ivory towers, or in enchanted castles with satins, furs and cloths of gold...and always happy endings.”

Angus was born on 8th June 1904 in Newbridge, Monmouthshire, in what seems like a far cry from London’s theatrical scene of the 1930s and 1940s that would make him one of the most influential photographers of the 20th Century. His father, Clement, was a chartered surveyor. He was educated at Monmouth Grammar School and Newport Technical College, and in his late teenage years worked as a bank clerk. However, his childhood interest in the makeup of a visiting actress and the purchase of an early Kodak perhaps hinted at what was to come. After being introduced to amateur dramatics by an aunt, he began designing posters, costumes and masks for the first time.

His father died at 47 years old, having contracted TB when fighting in the trenches, and the family moved to London. Angus was briefly married during this time (1923-24) to Helena Wood, although given that Angus was a homosexual, it is unsurprising that they separated a year later with no children.

He began working at Liberty’s Department store in London, where he developed the eccentric style of dress that he became known for. After leaving Liberty’s he attracted the attention of society photographer Hugh Cecil, who took him on as an assistant and taught him about the art of photographic portraits. His first job as a theatre photographer was for The Happy Hypocrite at His Majesty’s Theatre in 1936, starring Ivor Novello. The intensely dramatic photographs that he produced were unlike anything seen before.

It was Angus who took photographs during the now lauded years of the late 1930s at the Old Vic, which saw Laurence Olivier’s first performances in Macbeth, Hamlet and Henry V. His other subjects included Vivien Leigh, who became a muse of his. It was Angus’ photograph that was sent to David Selznick, preparing to cast Scarlett O’Hara in Gone with the Wind. He never photographed the Queen, reporting that he would have been ‘shaking with fear,’ and never moved into society photographs like his mentor Cecil, calling it all ‘a Bond Street Game I never played.’ He also became popular for his ability to retouch the photographs he took.

It was in 1942 that he was sentenced to four years in prison for homosexual practices. It might be expected that this would have meant the ruin of his life; he reportedly collapsed in the dock as his sentence was read out. However, the commissions were still there for accepting and Angus carried on much the same after his release. It was a similar case with his friend, the legendary actor John Gielgud who was arrested in 1953 for cruising for sex in a public toilet. He feared the disgrace would end his career, but the audience of his next performance gave him a standing ovation. This is probably reflective of how much more liberal the arts world was, then as now, compared with other sections of society. After his release, Angus also appeared as a witness at the trial of his friend and lover Quentin Crisp, who had been charged with soliciting.

Angus passed away in 1990. His photographs are now held by, among others, the Harvard Theatre Collection, the Victoria and Albert Museum, the British Library, the National Portrait Gallery and the Shakespeare Library.

‘Put the camera into the hands of an artist and a very different kind of photography will emerge.’