Preservation of geological collections - PhD studentship

, 9 June 2017

The numbers of specimens in geological collections in the UK alone reach into the tens of millions. These collections are important for research, education and also commercially. Museums hold collections, but so do individuals and companies; exploration companies keep rock core samples which can be as valuable as £1,000 per meter.

There is now sufficient evidence to dispel the myth that geological collections are inherently stable and require fewer resources to preserve them than other areas of museum collections. In fact, a proportion of geological collections demand a level of attention and maintenance comparable with archaeological metal collections. This includes similar environmental and pollution-related considerations.

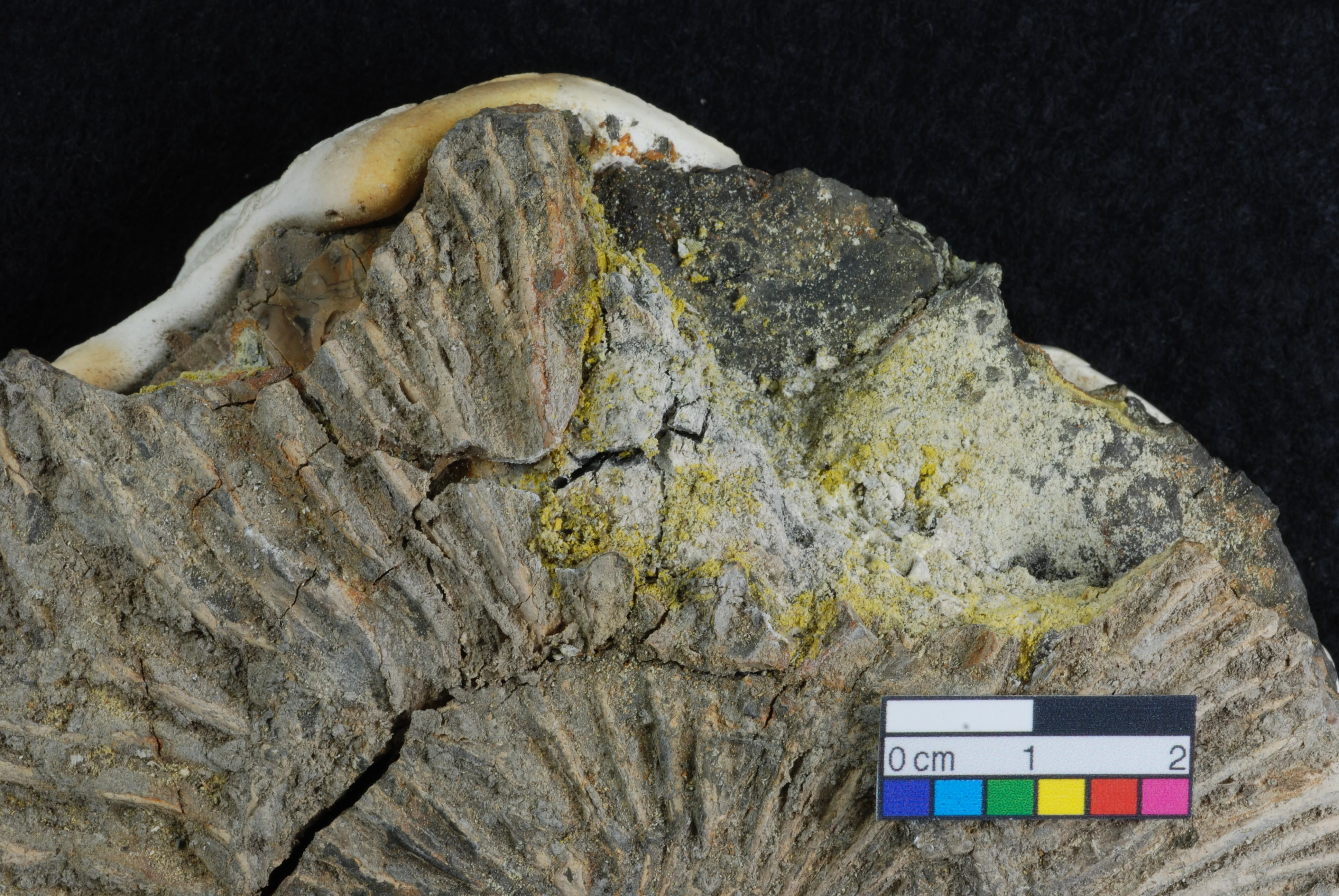

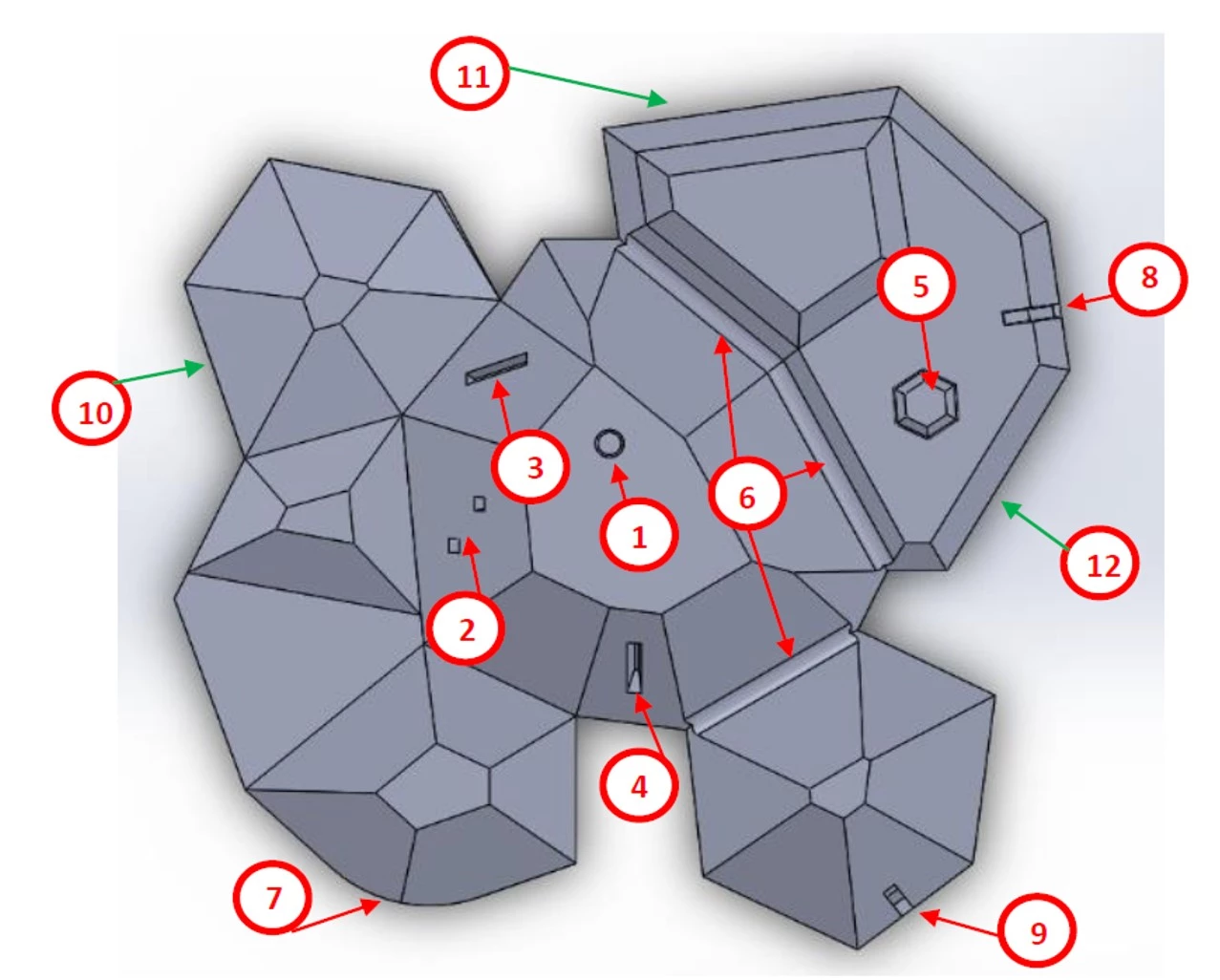

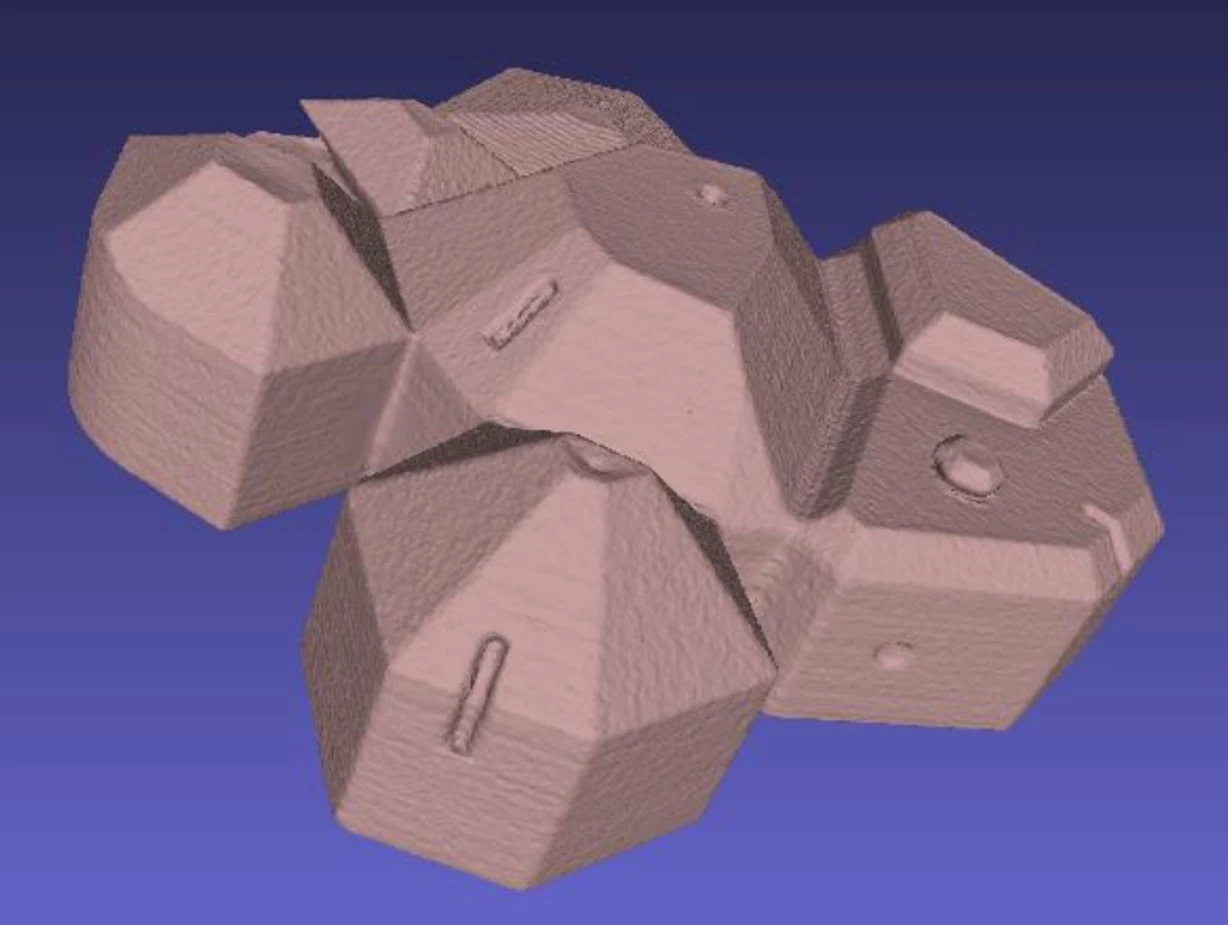

About 10% of known mineral species are sensitive to changes in temperature or humidity, or may react with air pollutants. One such mineral is pyrite – common in geological collections and one that is particularly troublesome. However, despite centuries of research on pyrite decay there is a dearth of knowledge in subjects that would help museums improve the effectiveness of their care of geological collections. This includes the categorisation of damage to specimens, methodologies for objective routine condition assessment, the definition of an adequate storage environment, and successful conservation treatments.

Currently available methodologies are not suitable for routine collection monitoring, results are not necessarily replicable, and, in the absence of guidance on suitable storage conditions, triggers and the suitability of conservation actions are difficult to determine. We need a more robust approach to the delivery of preventive conservation of geological collections.

We have now teamed up with the EPSRC Centre for Doctoral Training in Science and Engineering in Arts, Heritage and Archaeology (SEAHA) at University College London, University of Oxford and University of Brighton to investigate these aspects of preservation of geological collections. A four-year studentship has been advertised which will be based at Oxford University but spend a considerable amount of time working at National Museum Cardiff. If you are interested in this subject, and have a background in, ideally, geology, chemistry or engineering, please do get in touch.

Find out more about Care of Collections at Amgueddfa Cymru - National Museum Wales here and follow us on Twitter.