Conservation of Geological Museum Collections

, 8 February 2017

Rock collections in the UK are an asset worth millions of pounds. Many exploration companies drill into the Earth’s crust and extract cores for analysis – often at a cost of around £1,000 per meter of core. These provide the basic information before a commercial case for mining or extraction can be made and form part of the companies’ commercial archives.

Museums also look after collections and many hold large numbers of valuable geological samples. A common misconception is that rocks are stable, they do not decay or get eaten by pests. Which is why fossils, minerals and rocks surely must be easy to look after.

But think of minerals found in caves or mines: not just dark, but also cold and damp. Many hydrated minerals occur here, for example melanterite or halotrichite. Take them out of the mine, put them in a museum store where they are protected and well looked after – and they will dehydrate. Lose water molecules, decay, and are lost.

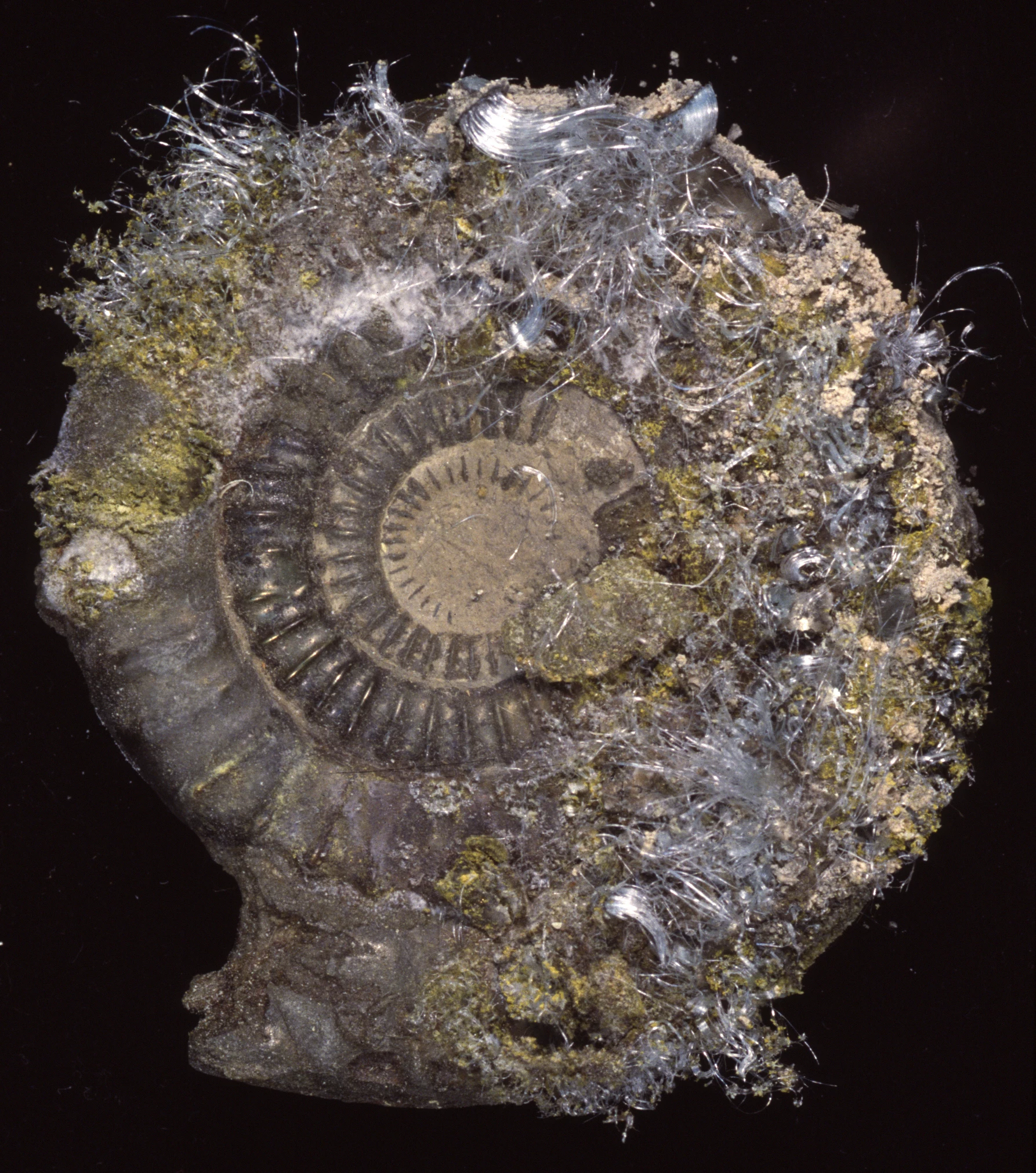

There are many similar examples. Depending on the mineral species they will take up or lose water molecules, recrystallize into something else, react with air pollutants or oxygen. A bewildering range of chemical processes can lead to the destruction of geological specimens. Fossils are affected, too: lovely pyritised ammonites turn to dust. Many specimens of scientific or historic importance can be lost in this way.

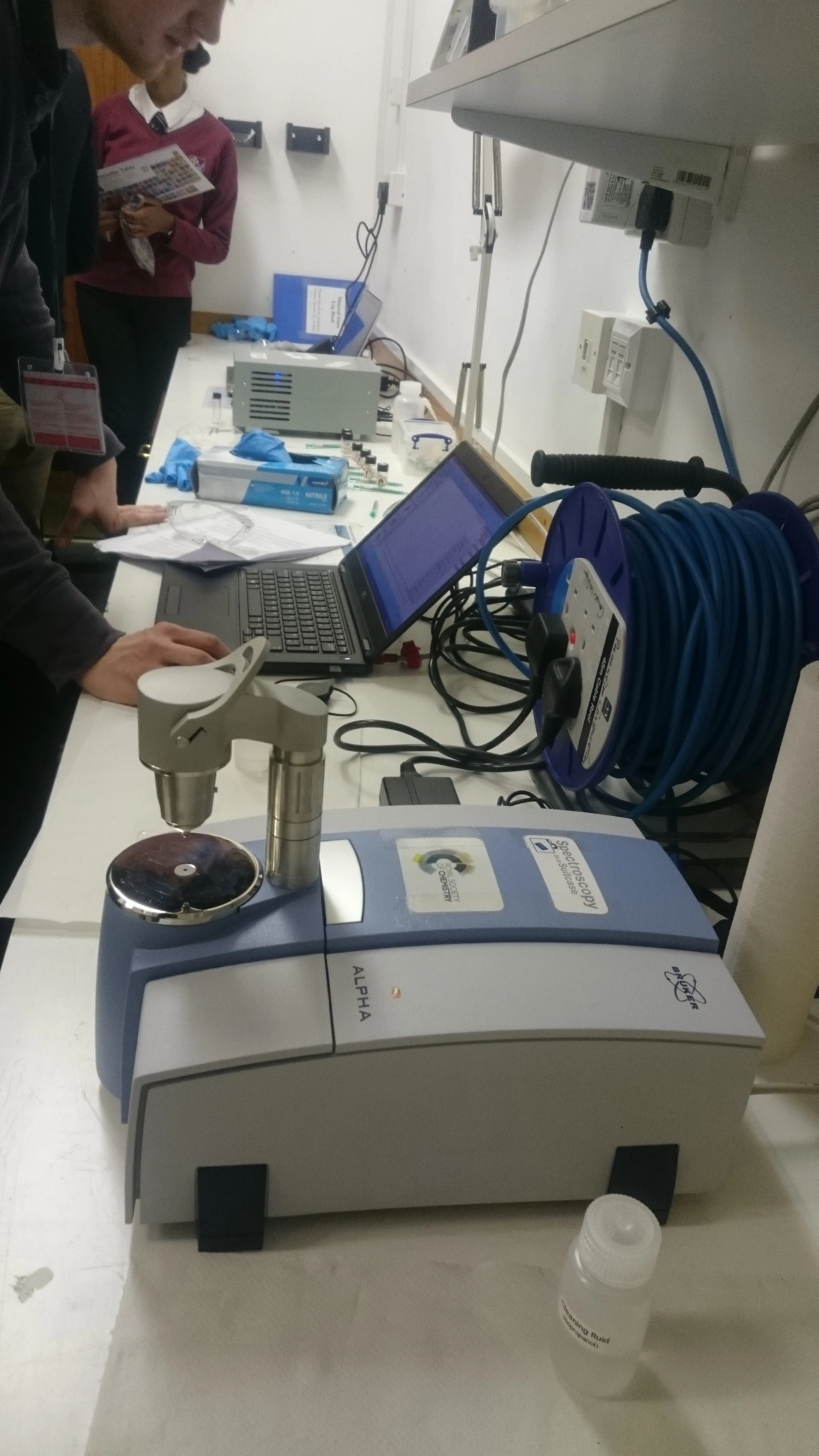

Museums do their best to halt the decay but are hampered in their efforts by many questions yet unanswered. What levels of indoor air pollutants are safe for geological collections and how good do our air filtration systems need to be? At what point do museum conservators need to deal with a specimen damaged by chemical reactions? How do we even monitor collections of tens of thousands of specimens for damage routinely?

These and many other related questions will be investigated in a new research project at National Museum Cardiff. A recent pilot study (manuscript in preparation) demonstrated the complexity of potentially damaging processes in a typical museum store that are thought of usually as benign. Further expertise in the form of academic and industrial partners is now sought to develop the potential for addressing elementary questions of appropriate storage of geological collections.

The knowledge generated by this project will be of wide-ranging interest to cultural institutions and industrial companies alike. Scientific specimens and commercial collections will be kept safe with the set of guidelines and standards which the project will develop. We will have the proper tools to enable us to care for our geological heritage appropriately - whether kept in museums or as commercial assets.

Find out more about Care of Collections at Amgueddfa Cymru - National Museum Wales here.