Falkland Islands 2013 January 16th update

, 16 January 2013

Due to a technical hitch the sampling at Whalebone Cove was postponed. Low tide was in fact 2 hours later than I thought as I had subtracted rather than added 1 hour for summertime, oops! Instead I got on the road to make the tide in the north (which I had worked out correctly). Three hours in the car brought me to Race Point Farm near Port San Carlos. This is in the northwest of East Falkland and had a very rocky shore with some large crevices in the rocks. These crevices could be split open with a spade and inside, hiding in the built up silt, were some very large worms indeed of the family Eunicidae (also known as ‘bobbit worms’ – google the phrase and you’ll find some footage of relatives of these worms hunting). The biggest of these measured around 20cm in length and as these worms have jaws I kept my fingers well away from the bitey end! The wind was whistling around the shore and despite being summer, my fingers were certainly cold. There was plenty to find though with colourful paddleworms being particularly common (photo 1). My bed for the night was a surprisingly cosy caravan at Elephant Beach Farm slightly further north. Despite how this sounds it really was comfortable, being fully equipped with power, hot shower and cooker and, even better, a freshly baked loaf of bread and some fresh eggs from the hens outside my door to keep me going.

Port Salvador was the next port of call and after calling in on the landowner, Nick Pitaluga, for a chat, he very kindly offered to drive me up to near Cape Bougainville right on the north tip of the coastline to sample there. This had originally been where I wanted to go but the road does not go that far and I had no desire (or permission) to take the hire car off road. The bone-rattling drive there, mostly on a visible track but the last part just generally cross-country toward the sea, confirmed that I would never have made it even halfway there without a guide. The exposed coastline was unsurprisingly rocky with long ledges of rock running out from the shore (photo 2). The tides are very low right now and the ledges were exposed right down into the kelp zone, where the enormous blades (nearly 1cm thick) of Lessonia kelp draped themselves over the rock and were so heavy they could barely be moved out of the way (photo 3). Underneath, in the cool damp crevices I found long tubes cemented to the rock. These turned out to be the home of large sabellariid worms (Phragmatopoma sp. photo 4), a relative of which lives in the UK and is known as the honeycomb worm for the tubes and occasionally reefs, it builds. Out here, this worm also sometimes creates reefs although here the tubes were individual. The worms inside are large, over 5 cm in length. I didn’t find any specimens of this family last time I was here so this was a very exciting find for me. Several scaleworms were also found sheltering in the crevices (photo 5).

On the drive back to the settlement I could see the sandy shores near it now exposed by the tide. These looked interesting so I decided to go back to the area the next day to do some digging there. This turned out to be a very rich beach and it was easy to see why there were so many wading birds around. The shore was literally covered with worm-holes and casts (photo 6) and I spent 3 hours working my around and down the shore with the tide. The weather by this time had changed from occasionally sunny (constantly windy) with a need for suncream even though I was feeling mildly hypothermic to mostly sunny with a feeling that I really might actually need the suncream (still windy).

On the drive back to Stanley that evening I felt that the first few days collecting had gone well. My main current concern is the fact that everyone I meet keeps trying to feed me either tea and cake or tea and biscuits (occasionally both). I have now given up on my post-Christmas attempt to wean myself off sugar.

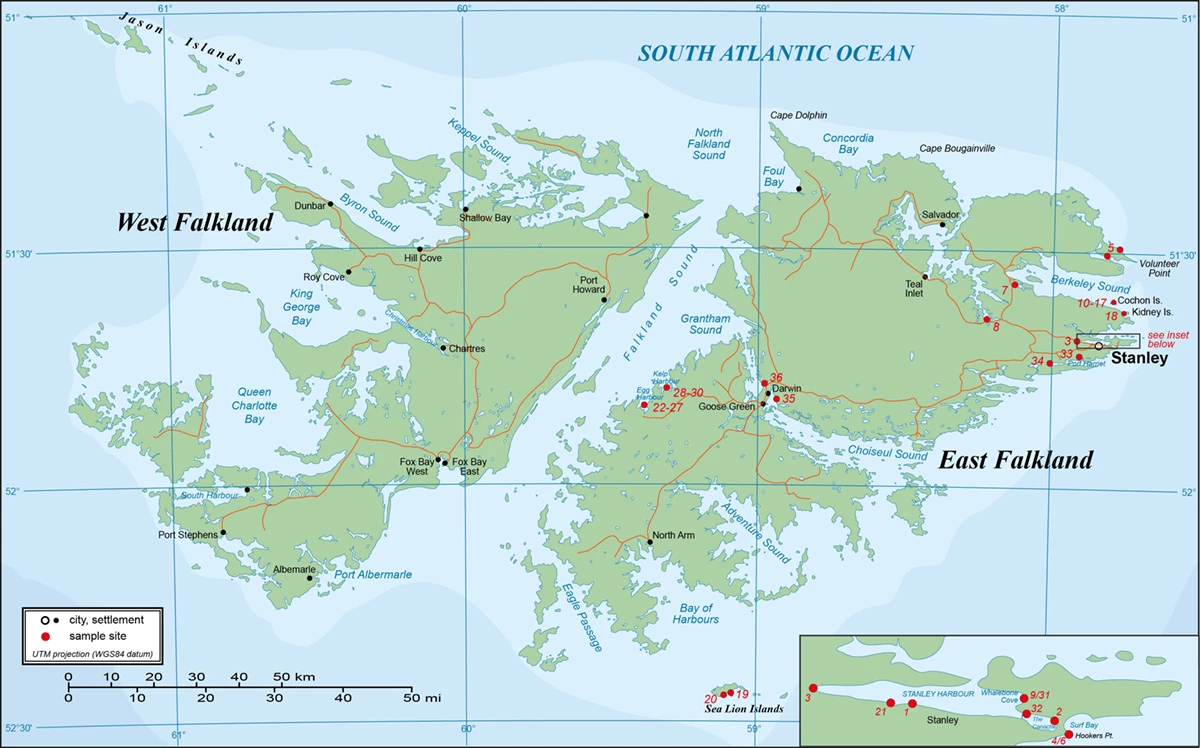

On Wednesday I made it to Whalebone Cove having now worked the tides out properly. Amazingly the wind had dropped (not stopped obviously) which helped the tide go out as low as possible. This was important because I was after some particular lugworms that are only found at very low water. I found these last time and they appear to be different to the others higher up the shore. However, I didn’t find very many before so I needed to collect more to be sure that differences I see are not just natural variation but a definite consistent difference in body form. The wind and tide were kind and allowed me to get what I needed so then it was back to the lab to inspect my catch. Photo 7 shows a map with the locations of the sites mentioned above.