Dillwyn’s Book of Algae. A glimpse into the scientific life of a 19th century philanthropist in Wales

, 1 July 2020

Lewis Weston Dillwyn (1778-1855)

Lewis Weston Dillwyn is part of the influential Dillwyn family in south Wales during the 19th century. They were pioneers in photography, culture, industry, politics and science. Lewis Weston himself was a campaigner for social justice, a Whig MP for Glamorgan (1832-37), mayor of Swansea (1839) and a magistrate. He studied the natural world and advanced our scientific understanding of it, becoming a Fellow of the Royal Society and a founder member of the Royal Institution of South Wales.

Lewis Weston was born 1778 to William Dillwyn, an American Quaker and anti-slave campaigner. After settling in England in 1777, William was one of the 12 founding committee members for the Society for Effecting the Abolition of the Slave Trade formed in 1787. In 1802, William established Lewis Weston Dillwyn, then aged 25, as owner of Cambrian Pottery in Swansea. A year later Lewis Weston moved to south Wales and four years after that married Mary Adams, heiress of John Llewellyn, firmly establishing the Dillwyn-Llewellyn family’s influential position in south Wales. He was an abolitionist like his father but was also close friends with the De la Beche family who owned slave plantations up until the early 1830s. His son Lewis Llewellyn Dillwyn married Elizabeth De la Beche in 1838.

It was mainly during the time he was head of Cambrian Pottery that Lewis Weston studied algae.

The Book of Algae

Lewis Weston had a scientific interest in the natural world, most notably plants, beetles and molluscs. At a time when art, industry and science were often pursued in conjunction with one another rather than separately, he introduced many natural history designs onto the products made at his Cambrian Pottery.

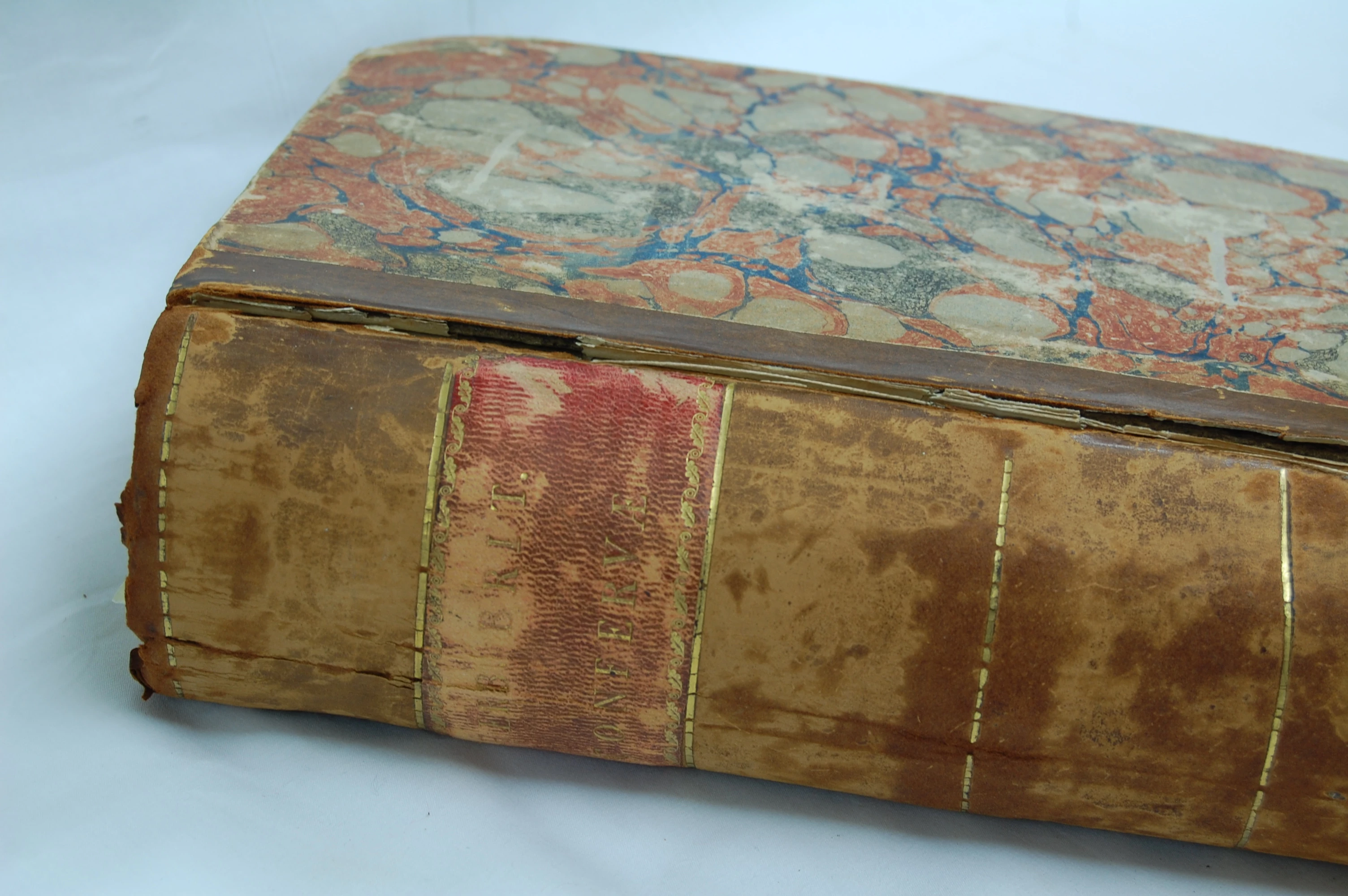

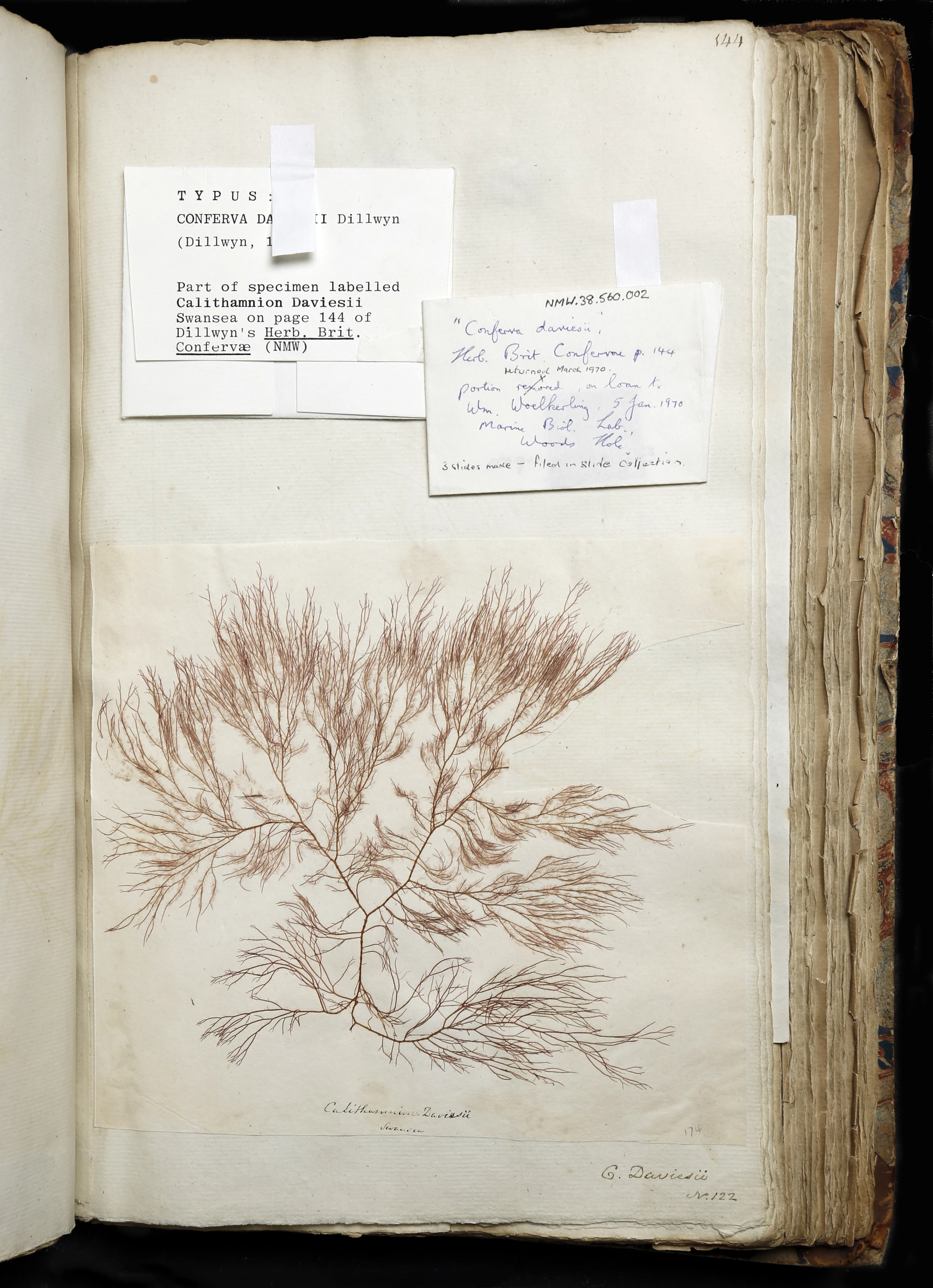

The Museum holds Lewis Weston Dillwyn’s book of pressed seaweeds and algae. Inside are over 280 specimens of algae from both fresh and seawater, mainly from Wales and England. Many are thought to have been collected by Dillwyn himself, and many were sent to him by scientists from the UK and Ireland. The book contains algae that were completely new to science and described by Dillwyn for the first time. Some of these new to science algae were discovered for the very first time in Wales. The book is an early record of the natural heritage of Wales and a glimpse into the scientific life of a prominent 19th century philanthropist.

New to Science

It was particularly between 1800 and 1810 that Lewis Weston Dillwyn focussed on algae. He noted that Linnaeus, who was classifying the whole of the natural world, “was too busily engaged in the immense field he had entered on, to spare the time necessary for an investigation of the submerged Algae.” (Dillwyn, 1809, British Confervae). Dillwyn felt he had found a niche for his scientific study.

The algae that Lewis Weston studied was a group with very thin fine branching known as the Confervae. He collected specimens, pressed them and placed them into the book now held at the Museum. His many connections led to a network of scientists who would send him specimens he was interested in to his home in south Wales. He described 80 kinds of algae new to science.

Someone in Dillwyn’s position could afford to buy a microscope powerful enough to study this group which have very small features. He would also have needed expensive books and his standing in society meant he was able to access the libraries of friends such as William Jackson Hooker and of the Linnaean Society in London, where he was made a Fellow. It also meant he was able to discuss current thinking with other prominent scientists of the time and gauge where to place his efforts.

At the time, there had been little work done on this difficult to study group. Dillwyn knew the algae he was looking at were probably unrelated, but in his published work he put them into one group. He had done the initial pioneering groundwork to describe them but he himself modestly admitted that it was flawed. The pressed algae in his book at the Museum includes what scientists now know belong in many different groups: green algae, red algae, brown algae, lichens, fungi, cyanobacteria, stoneworts and diatoms. Dillwyn published the results of his studies in instalments, culminating in the publication ‘British Confervae’ in 1809.

Further reading

The Diaries of Lewis Weston Dillwyn, transcribed by Richard Morris: https://www.swansea.ac.uk/crew/research-projects/dillwyn/diaries/lewis-weston-dillwyn-diaries/

The Dillwyn Dynasty by David Painting (2002): https://www.swansea.ac.uk/crew/research-projects/dillwyn/dillwyn-day/dillwyn-dynasty/

British Confervae by Lewis Weston Dillwyn: https://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/bibliography/2189#/summary