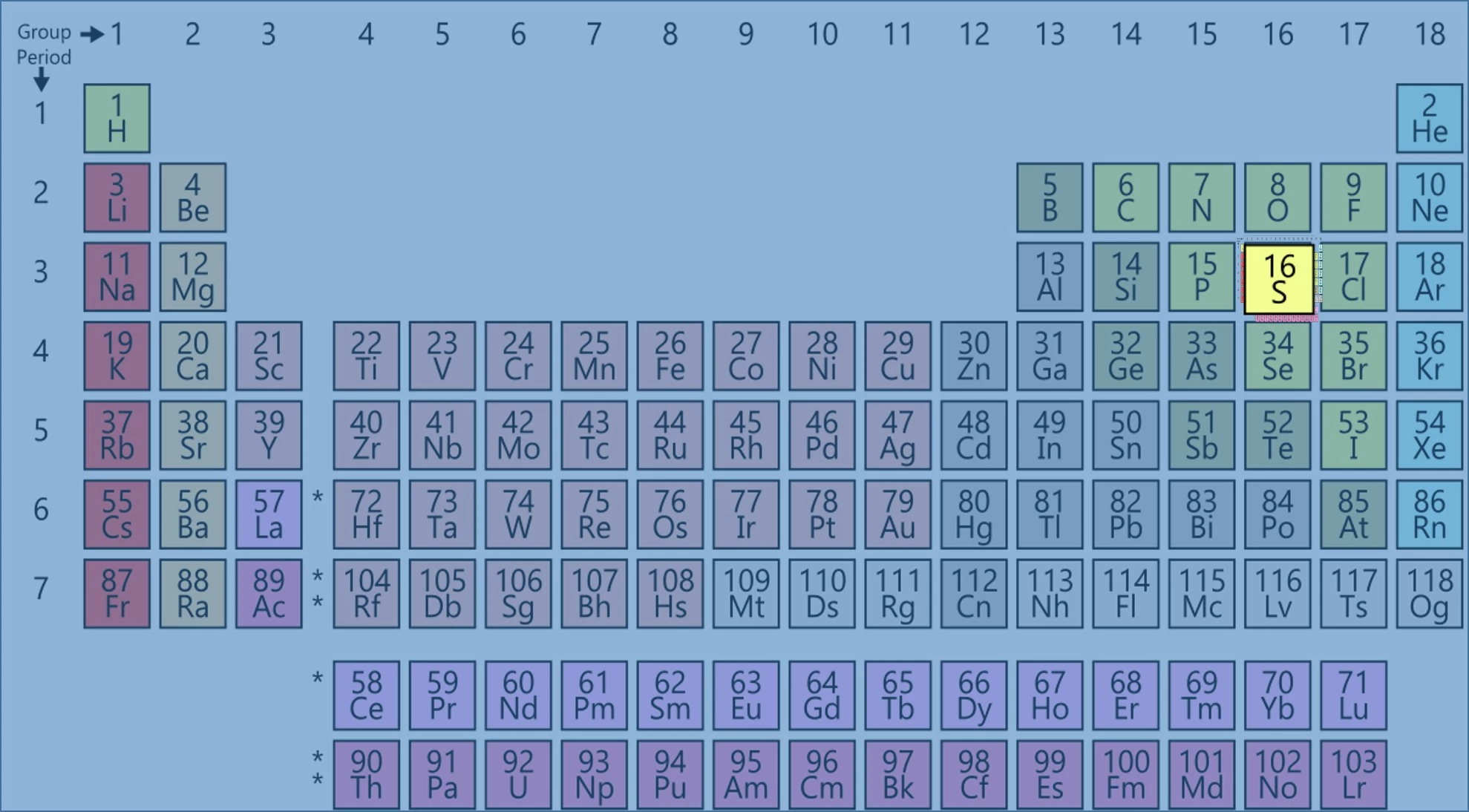

2019 is the 150th anniversary of the Periodic Table of Chemical Elements (see UNESCO https://www.iypt2019.org/). The "International Year of the Periodic Table of Chemical Elements (IYPT2019)" is an opportunity to reflect upon many aspects of the periodic table, including the social and economic impacts of chemical elements.

Sulphur is the fifth most common element (by mass) on Earth and one of the most widely used chemical substances. But sulphur is common beyond Earth: the innermost of the four Galilean moons of the planet Jupiter, Io, has more than 400 active volcanoes which deposit lava so rich in sulphur that its surface is actually yellow.

Alchemy

The sulphate salts of iron, copper and aluminium were referred to as “vitriols”, which occurred in lists of minerals compiled by the Sumerians 4,000 years ago. Sulfuric acid was known as “oil of vitriol”, a term coined by the 8th-century Arabian alchemist Jabir ibn Hayyan. Burning sulphur used to be referred to as “brimstone”, giving rise to the biblical notion that hell apparently smelled of sulphur.

Mineralogy

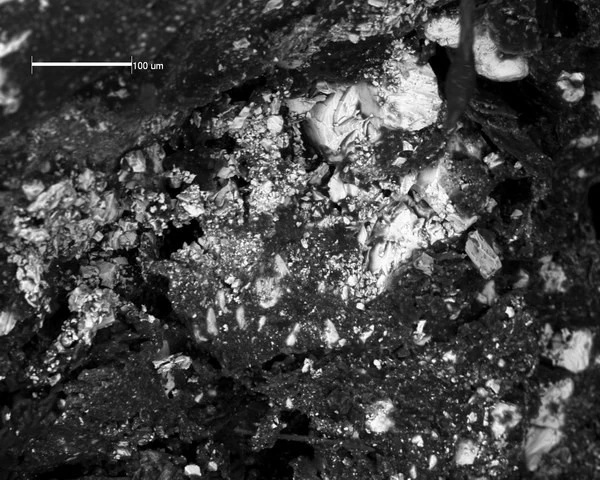

Sulphur rarely occurs in its pure form but usually as sulphide and sulphate minerals. Elemental sulphur can be found near hot springs, hydrothermal vents and in volcanic regions where it may be mined, but the major industrial source of sulphur is the iron sulphide mineral pyrite. Other important sulphur minerals include cinnabar (mercury sulphide), galena (lead sulphide), sphalerite (zinc sulphide), stibnite (antimony sulphide), gypsum (calcium sulphate), alunite (potassium aluminium sulphate), and barite (barium sulphate). Accordingly, the Mindat (a wonderful database for all things mineral) entry for sulphur is rather extensive: https://www.mindat.org/min-3826.html.

Chemistry

Sulphur is the basic constituent of sulfuric acid, referred as universal chemical, ‘King of Chemicals’ due to the numerous applications as a raw material or processing agent. Sulfuric acid is the most commonly used chemical in the world and used in almost all industries; its multiple industrial uses include the refining of crude oil and as an electrolyte in lead acid batteries. World production of sulfuric acid stands at more than 230 million tonnes per year.

Warfare

Gunpowder, a mixture of sulphur, charcoal and potassium nitrate invented in 9th century China, is the earliest known explosive. Chinese military engineers realised the obvious potential of gunpowder and by 904 CE were hurling lumps of burning gunpowder with catapults during a siege. In chemical warfare, 2,400 years ago, the Spartans used sulphur fumes against enemy soldiers. Sulphur is an important component of mustard gas, used since WWI as an incapacitating agent.

Pharmacy

Sulphur-based compounds have a huge range of therapeutic applications, such as antimicrobial, anti-inflammatory, antiviral, antidiabetic, antimalarial, anticancer and other medicinal agents. Many drugs contain sulphur; early examples include antibacterial sulphonamides, known as “sulfa drugs”. Sulphur is a part of many antibiotics, including the penicillins, cephalosporins and monolactams.

Biology

Sulphur is an essential element for life. Some amino acids (cysteine and methionine; amino acids are the structural components of proteins) and vitamins (biotin and thiamine) are organosulfur compounds. Disulphides (sulphur–sulphur bonds) confer mechanical strength and insolubility of the protein keratin (found in skin, hair, and feathers). Many sulphur compounds have a strong smell: the scent of grapefruit and garlic are due to organosulfur compounds. The gas hydrogen sulphide gives the characteristic odour to rotting eggs.

Farming

Sulphur is one of the essential nutrients for crop growth. Sulphur is important to help with nutrient uptake, chlorophyll production and seed development. Hence, one of the greatest commercial uses of sulfuric acid is for fertilizers. About 60% of pyrite mined for sulphur is used for fertilizer manufacture – you could say that the mineral pyrite literally feeds the world.

Environment

Use of sulphur is not without problems: burning sulphur-containing coal and oil generates sulphur dioxide, which reacts with water in the atmosphere to form sulfuric acid, one of the main causes of acid rain, which acidifies lakes and soil, and causes weathering to buildings and structures. Acid mine drainage, a consequence of pyrite oxidation during mining operations, is a real and large environmental problem, killing much life in many rivers across the world. Recently, the use of a calcareous mudstone rock containing a high proportion of pyrite as backfill for housing estates in the area around Dublin caused damage to many houses when the pyrite oxidised; the case was eventually resolved with the “Pyrite Resolution Act 2013” allocating compensation to house owners.

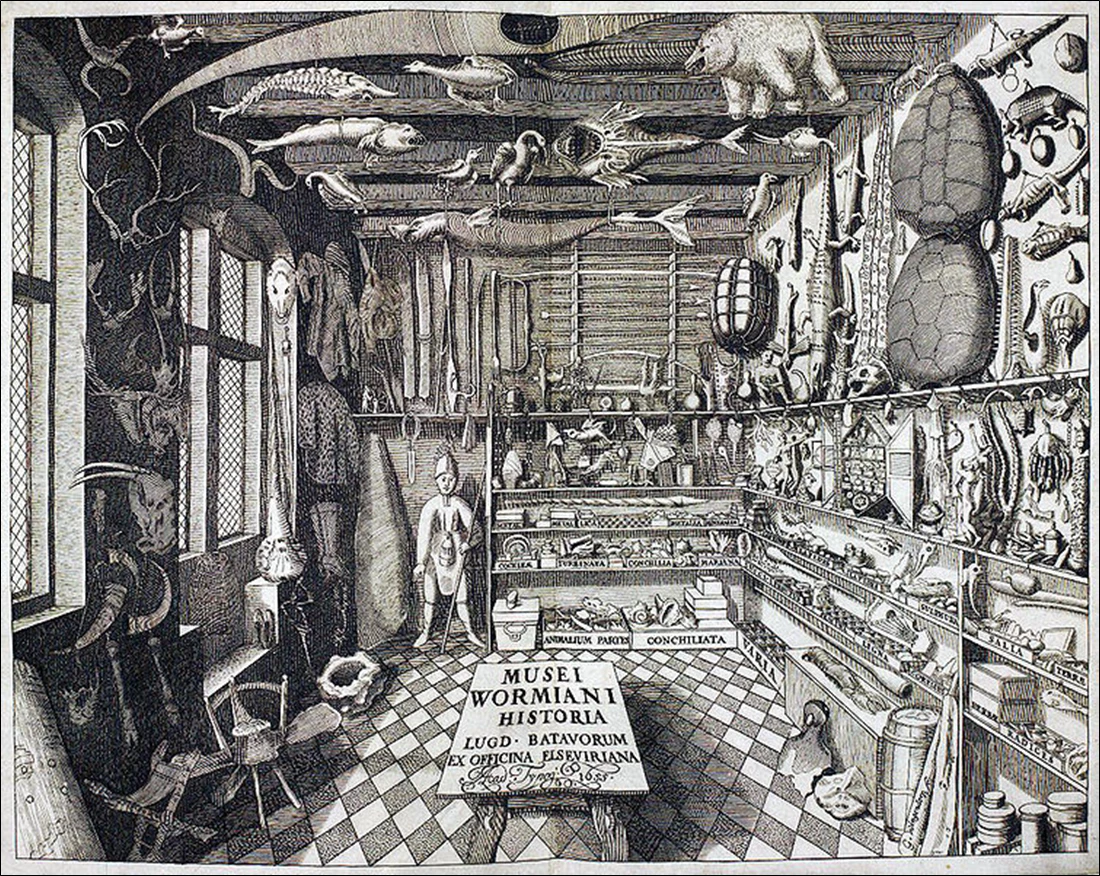

Conservation of museum specimens

Because iron sulphides are highly reactive minerals, their conservation in museum collections poses significant challenges. Because we care for our collections, which involves constantly improving conservation practice, we are always researching novel ways of protecting vulnerable minerals. Our current project, jointly with University of Oxford, is undertaken by our doctoral research student Kathryn Royce https://www.geog.ox.ac.uk/graduate/research/kroyce.html.

Come and see us!

If all this has wetted your appetite for chemistry and minerals, come and see the sulphur and pyrite specimens we display at National Museum Cardiff https://museum.wales/cardiff/, or learn about mining and related industries at Big Pit National Coal Museum https://museum.wales/bigpit/ and National Slate Museum https://museum.wales/slate/.