Let us visualise that for you

, 27 April 2017

Our collaborations with Cardiff University in the area of heritage science continue to grow. Just before Easter, Daniel Griffiths from the School of Engineering contributed towards our goal of developing monitoring tools for use by museum conservators.

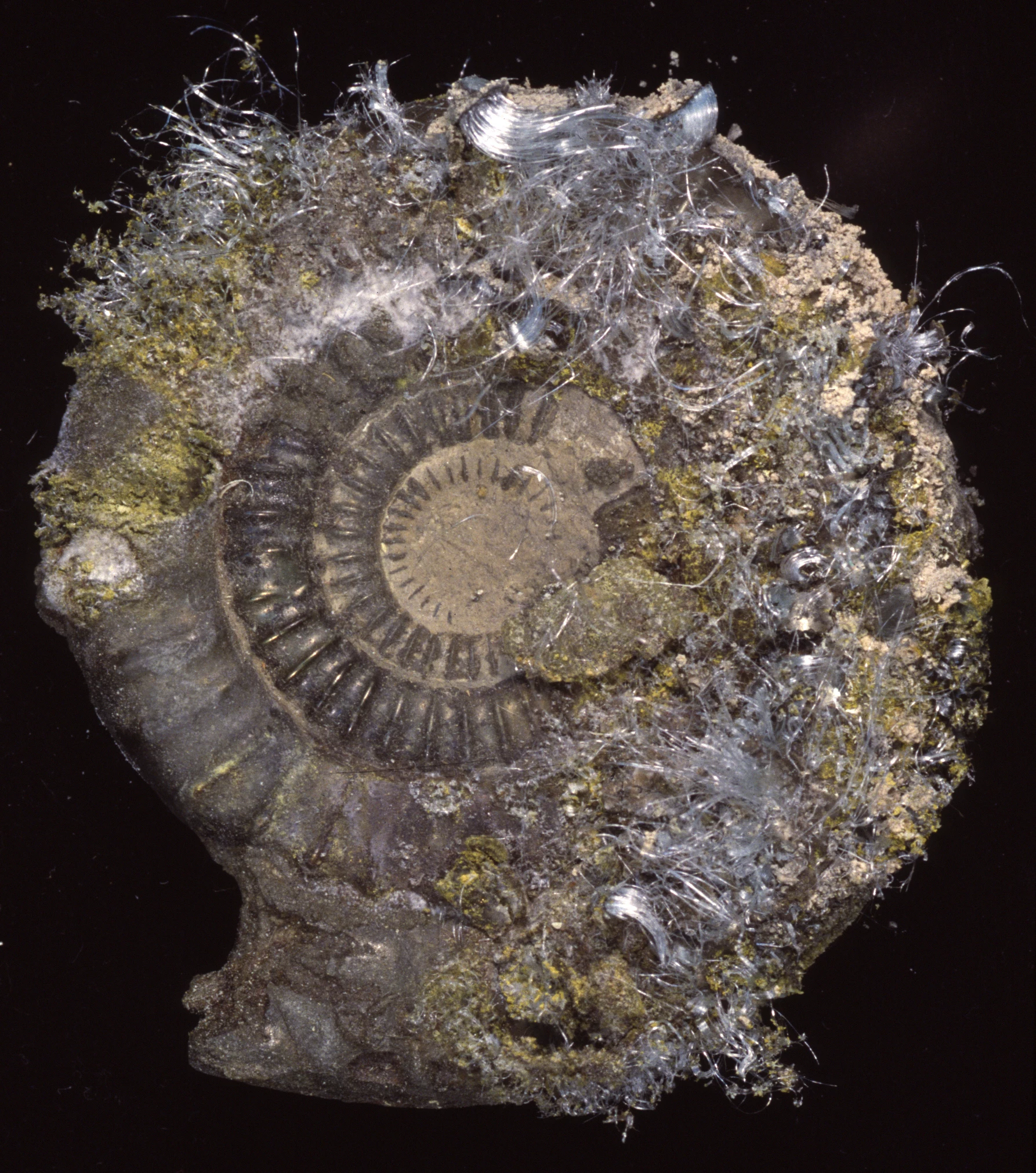

One of the routine tasks of conservators is to keep an eye on the condition of items stored in museums. Being responsible for looking after Amgueddfa Cymru - National Museum Wales’ five million objects, the team of less than 20 the conservators have their work cut out. In addition to the sheer number of objects in need of monitoring, for some categories of items there are currently issues with keeping adequate records for comparison with future condition assessments. We also want to objectivise the entire process to enable easier comparison between assessments undertaken at different times or by different people.

Presently, changes to collection items (if any) are detected by visual assessments and recording these in a text form, often supplemented with photographs. If such items are small and prone to chemical reactions, the results of which are difficult to describe, condition assessments are very difficult to undertake.

How do we make things easier, quicker and more objective? Daniel, a student in engineering, undertook a pilot study to create an overview of our options for non-invasive damage testing in geological specimens (specifically, in minerals). Some testing methods – such as acoustic emission, ultrasound, and X-ray and micro magnetic resonance imaging – were discounted early on in the project for various reasons. Any further techniques Daniel considered are based on imaging or scanning, grounded in the assumption that most damage to minerals is visible as changes in shape, integrity or colour.

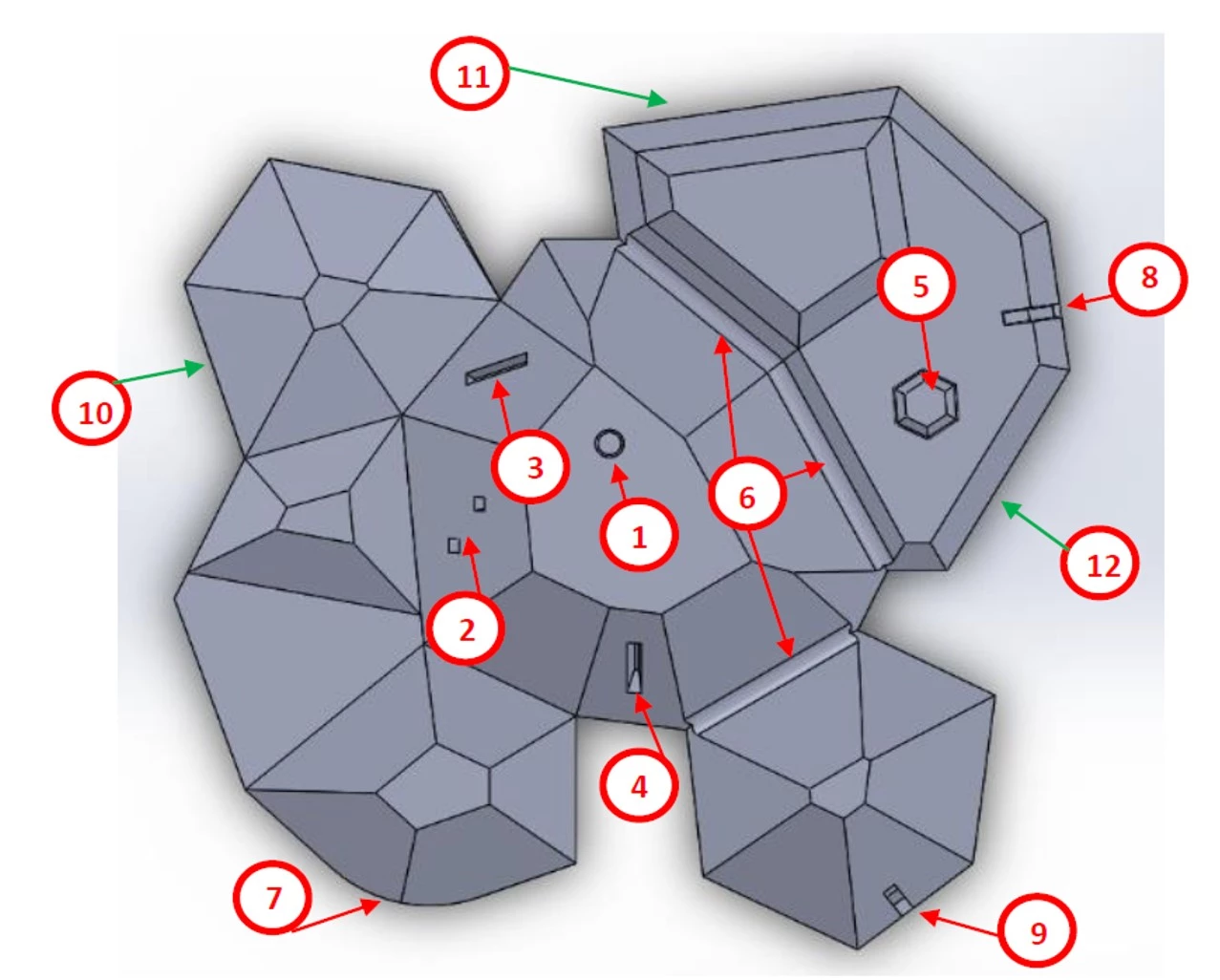

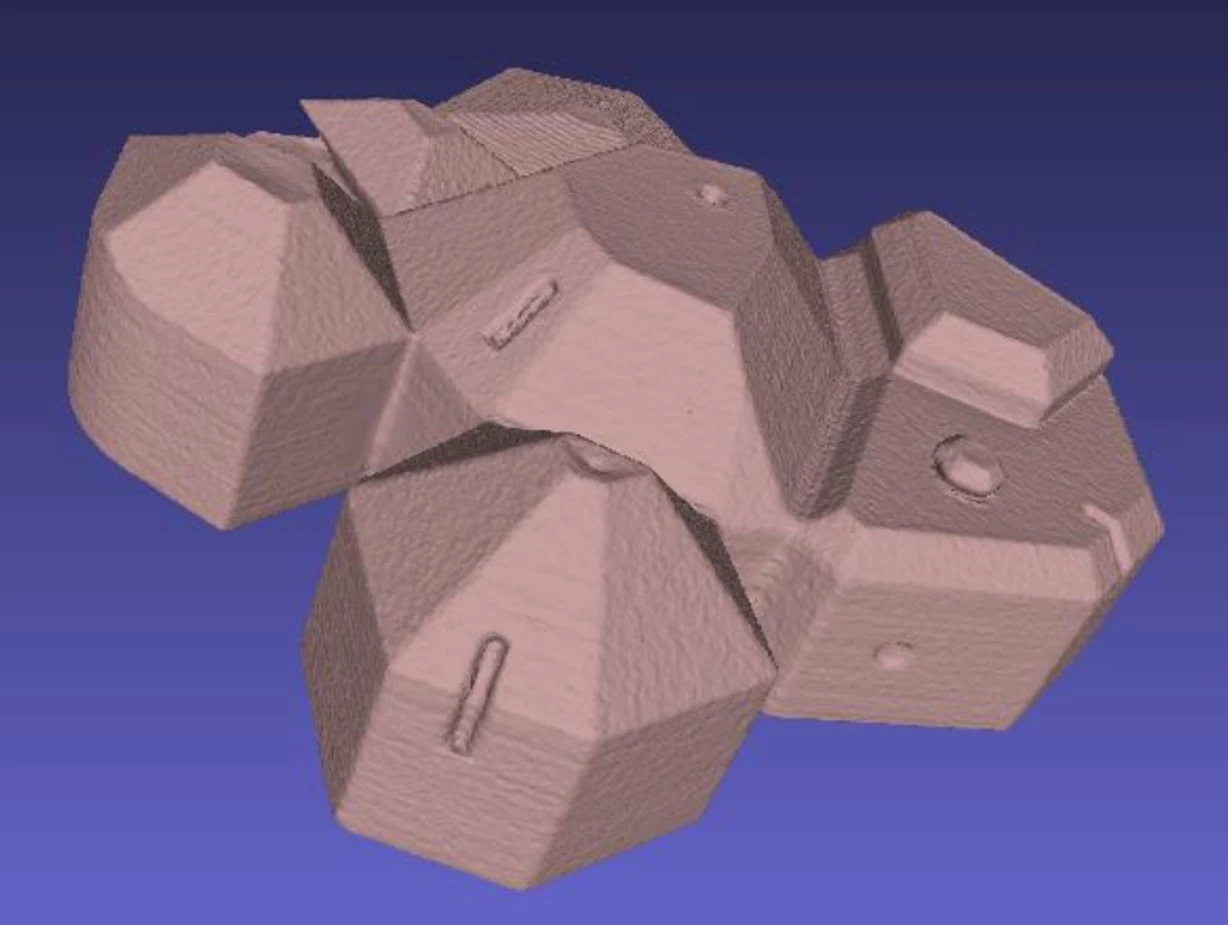

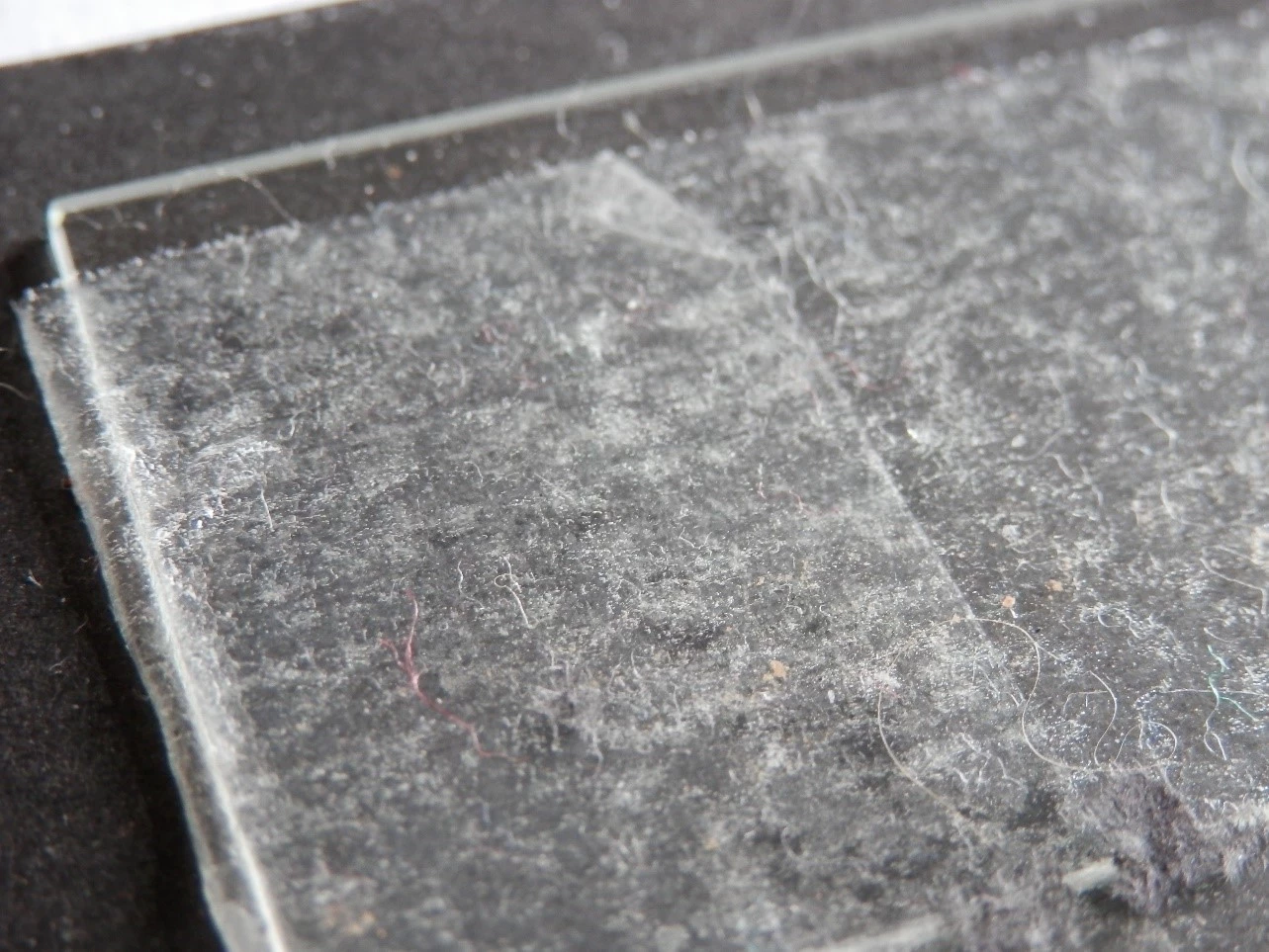

Initial thoughts on using artificially aged pyrite were replaced in favour of CAD-designed and 3D-printed models of ‘crystals’: one set ‘undamaged’ and a second ‘damaged’ set with deliberately introduced yet precisely known ‘decay features’, such as holes and cuts. Daniel then scanned or imaged these models and compared the results for speed, ease of use, cost effectiveness and accuracy of recording of ‘decay’.

The best results were obtained with the Artec Space Spider, a handheld high-resolution 3D scanner based on blue light technology with easy-to-use software. The downside of this technique is the high purchasing cost of this instrument and software. Mobile phone technology, which was one of the comparative techniques, is not yet evolved enough to provide useful (i.e., good image quality, faithful recording of defects smaller than 5mm diameter) results.

The results of this study are encouraging because they provide us with a good foundation for future development work. There are questions about the faithful recording of colour, especially of reflective crystal surfaces, and combining features of storage, processing and analysis of images through one single computer program.

Daniel was supervised by Prof Rhys Pullin and Dr John McCrory from Cardiff University’s School of Engineering. We thank both of them for their support and cooperation in this project.

Find out more about Care of Collections at Amgueddfa Cymru - National Museum Wales here.