Pollution in store – can science help?

, 9 June 2016

Dropping a rusty nail into a glass of Coca Cola will clean it in a matter of hours. We have all heard that one. Other drinks manufacturers are available, and alternative liquids will do the same job: lemon juice, vinegar, even salad dressings.

What causes the nail to go rusty in the first place is corrosion. Rust is the product of the corrosion of iron, and I bet my favourite chemistry book that you will have seen rust somewhere. Many other metals can corrode, too: aluminium, zinc, lead, copper etc. Corrosion is electrochemical oxidation; it usually needs water and oxygen to corrode a metal. If you drop a clean nail into a salt solution (electrolyte) it will start rusting within hours – the iron loses electrons and gains oxygen. The acidic liquids in the first paragraph appear to have the opposite effect but, in fact, dissolve the rust rather than convert it back to the base metal.

This blog is turning into a mixture of a cooking recipe and a heavy science article. What on Earth does all this have to do with museum collections? After all, we don’t allow food consumption in our galleries and stores so where does the vinegar come from?

Well, believe it or not we do have vinegar in the air in the museum. You do, too, at home. Along with formic acid, acetic acid (the thing that gives vinegar its zingy taste) can be air borne in indoor environments. Both acids are considered indoor pollutants. Hardly detectable outside, in certain conditions they can accumulate inside buildings – and then cause corrosion. Indoor air pollution has recently been in the press, but we are talking here of risks to museum objects, not health risks to people.

Where do these substances come from? Wood readily off gasses acetic and formic acids. Book cases, furniture, floor boards, the wooden boards your walls are made of – they all emit these substances. Normally, this is not a problem; we all ventilate our houses, and normally we don’t keep objects at home long enough for corrosion to be a problem. Or is it? My mother still polishes her silver regularly and keeps it safe – in a wooden cupboard. Make of that what you want. Perhaps she enjoys polishing.

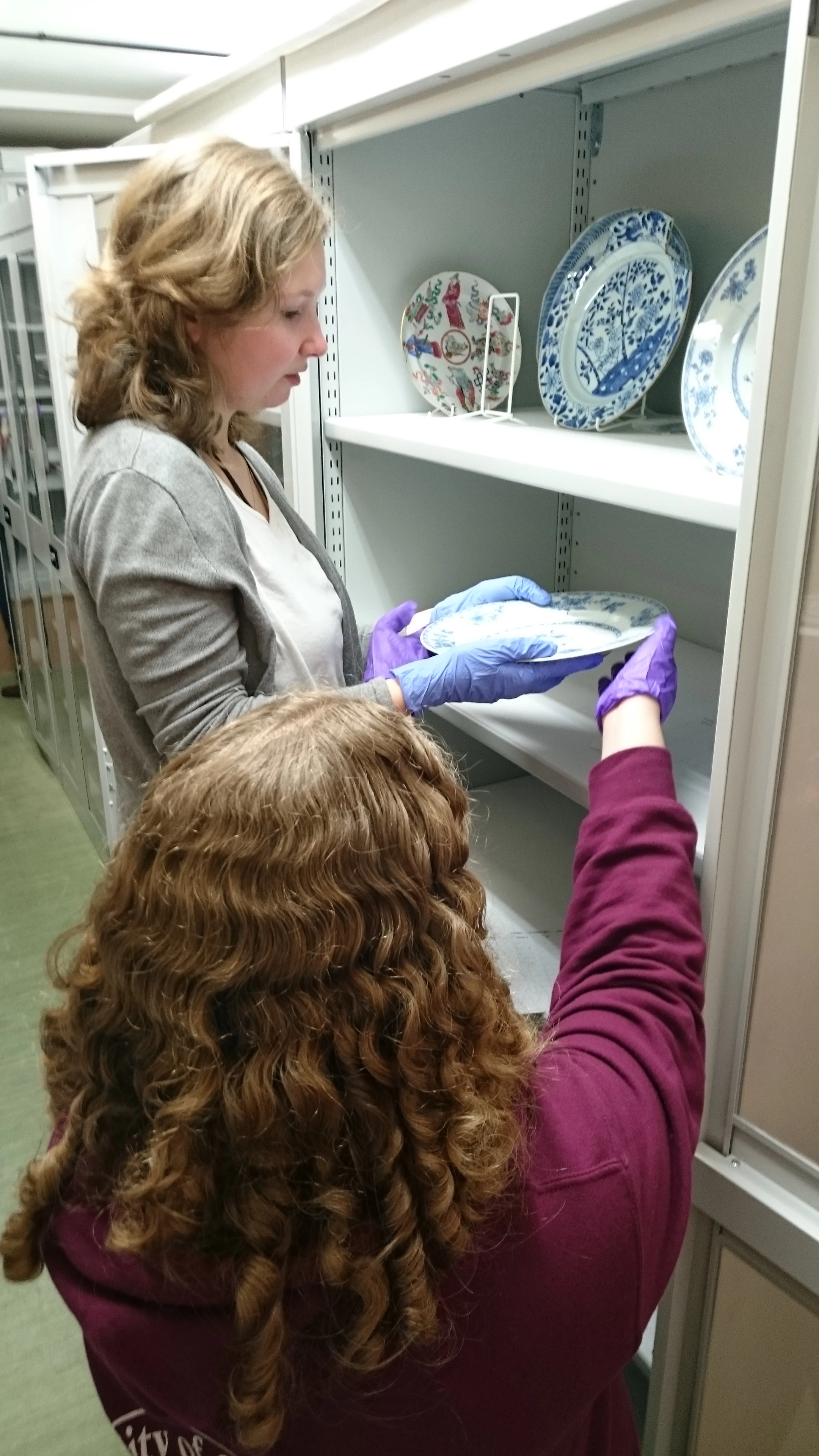

Your favourite museum has a lot of metal objects in its stores. And we are, of course, in the business of keeping objects safe not just for short periods of time, but for centuries. Over long periods of time we do notice corrosion on metal objects even if they merely sit on a shelf. We could go round cleaning these, like my Mum does, and give them a polish from time to time. Time consuming, I hear you cry. You lose a teeny tiny part of the surface each time you polish it, I hear you scream. And wouldn’t it be better to prevent corrosion in the first place, I hear you shout.

Right you are, I respond. After all, this is Preventive Conservation. We can measure the concentrations of air borne acids with good accuracy. We also know the sources of these acids. So when we detect signs of corrosion all we need to do is some simple investigating and – hey presto – come up with a mitigation plan. In some cases this might mean replacing old, wooden storage furniture. In others, we might have to introduce ventilation to a store to prevent pollutants from accumulating to harmful levels. Either way, the collections will benefit.

At National Museum Cardiff we have done both, and with good success. We have recently refurbished two stores with the sole aim of reducing indoor pollution. This was not cheap, but it is more cost effective than constantly polishing the silver ware - over and over and over again. It is because of these constant collection care improvements that we can say, hand on heart, your heritage is safe in the museum. And why we only eat fish and chips without vinegar in the museum. Only joking – food is still banned. Don’t let me catch you with any chips in the galleries!

Find out more about care of collections at Amgueddfa Cymru - National Museum Wales here.