The New Welsh

, 9 June 2021

Radhika Mohanram

No sooner had the Sri Lankan civil war ended, then the Syrian civil war began in 2011 and it is still ongoing. The war has currently resulted in over 13 million Syrians who have been either internally displaced within Syria, or in neighbouring countries, or in Europe and the rest of the world. Germany has over 800,000 Syrian refugees and the UK, a paltry 18,000-20,000 of them in 2021. The body count of Syrians who have died in this exodus is still not fully accounted for and the bottom of the Mediterranean sea, which is considered to be the deadliest migration route for refugees, has become a graveyard for them.

Neither the Sri Lankan Tamil nor the Syrian refugees sought refuge in the UK so they could shop in Tesco and take jobs away from the locals. They left their countries under desperate circumstances—the daily bombings, the kidnapping of children (and youth) by rebel soldiers forcing them into becoming child soldiers, the rape of women and children, the loss of jobs, homes, family members—spouses, children, parents, siblings--the lack of food, safety, and a full night’s sleep; it was the precarity of life.

In Homo Sacer, the Italian philosopher Giorgio Agamben points to the distinction made by the Ancient Greeks between bios (the form or manner in which life is lived and which assesses the richness of life) and zoë (the biological fact of life) and suggests that in contemporary life that distinction has collapsed. So, life now only means bare life, zoë. The biological fact of life with all its potentialities and possibilities has been erased. For the French philosopher Michel Foucault, modern power is about “fostering life or disallowing it.” This is how civilian populations in Sri Lanka and Syria were perceived by their governments—a full life disallowed for some of its citizens so that they are reduced to a bare life, their only possibility being to flee. This is how refugees are perceived in the current political climate with hostile environment policies, to be seen as only deserving of a bare life, to show how unwelcome they are.

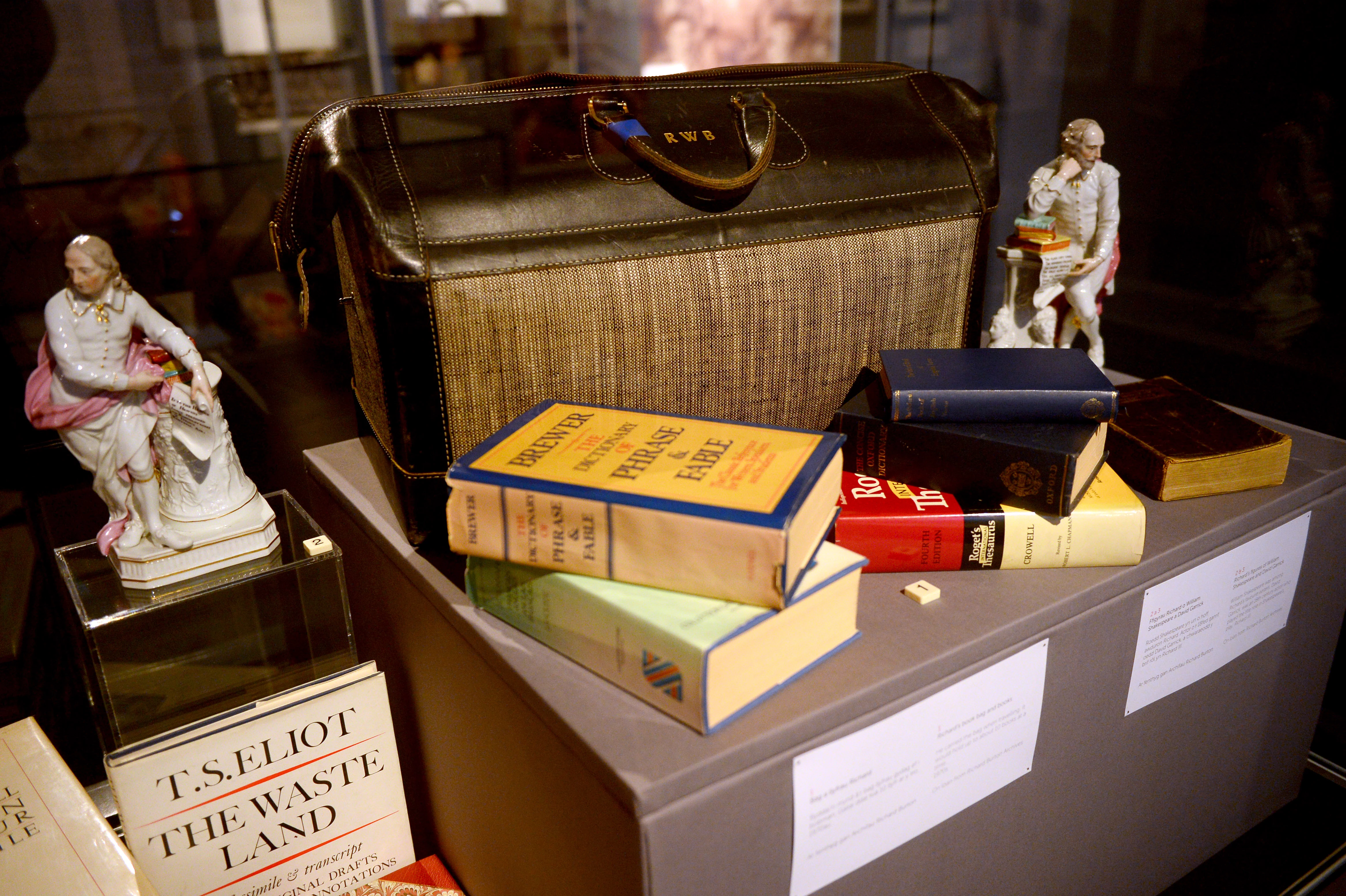

If by moving away from their country results in a total and complete break from their past lives for the refugees, a rupture from their histories and cultures, what this project hopes to achieve is to allow refugees to connect their past to their present, give them a voice, and a sense of belonging and that people are, indeed, witnessing their trials. The Museum with the richness of cultural life that it offers, through its resources, will assist in enabling refugees to become citizens of Wales, and help them to transform their lives in the country that is now their home; it will facilitate and contribute to them leading their lives into the fullest of its potentialities and possibilities.

And those of us who already live in Wales, how will these newcomers change our lives? By hearing their stories, we, too, will reach further into our potentiality, of the richness of diversity, compassion, being good hosts and helping them go through their transformation and, in so doing, initiate new ways of being and becoming Welsh.