United Nations international year of the periodic table of chemical elements: August - arsenic

, 21 October 2019

Continuing the international year of the periodic table of chemical elements, for August we have selected arsenic.

Preserving the Beasts – The Use of Arsenic in Taxidermy

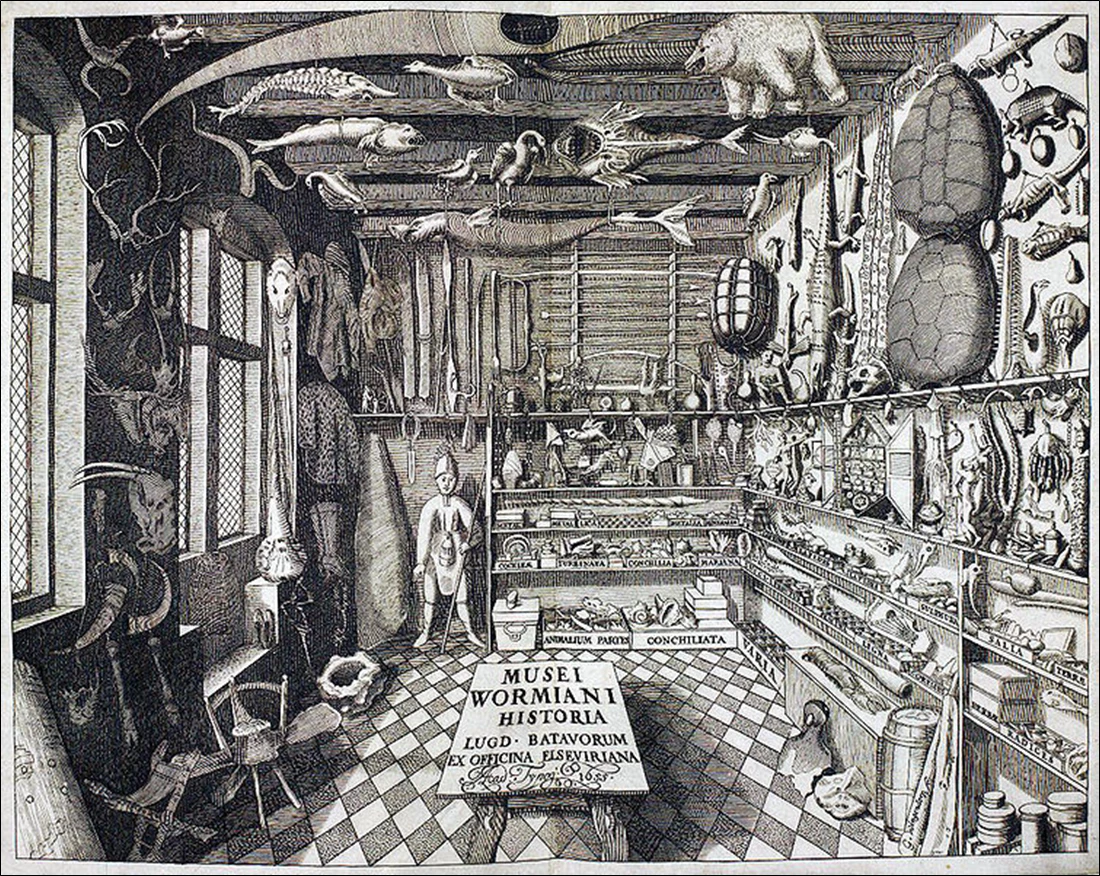

The taxidermy animals are a much loved and visited part of displays at the Museum. The word ‘taxidermy’ itself comes from taxis ‘arrangement’ and derma ‘skin’, and is the art of mounting or replicating animal specimens in a lifelike way for display or study.

The development of the methods used to create taxidermy date back over three hundred years. Initially these didn’t preserve the prepared specimens very well, and the taxidermy mounts were usually lost to decay and insects.

Various attempts were made to improve preservation methods and these used a wide variety of materials such as herbs, spices and various salts, applied as powders, pastes and solutions. However these methods were not generally successful.

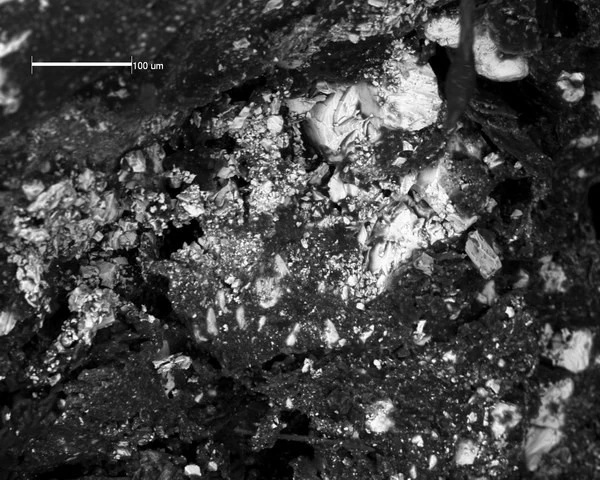

During the 1700s’ some taxidermists started to use more poisonous chemicals such as arsenic minerals or mercuric chloride to help preserve their taxidermy. Due to their toxic nature these treatments helped prevent decay and insect damage, greatly improving the long term preservation of the taxidermy.

The success of these chemicals soon led to the development of the ‘arsenical soap’ treatment to aid preservation of the animal skin. The soap was a mix of camphor, powdered arsenic, salt of tartar, bar soap and powder lime – I wouldn’t use this for washing yourself though! The soap enable the arsenic to be applied in a practical way by rubbing into the underside of a cleaned and prepared skin. This method proved very popular and remained in use up until as recently as the 1970s’.

The use of arsenic as part of the preservation treatment has since stopped. This is mainly because of its toxic nature and the associated risks to human health, but it is also due to better practices in the taxidermy techniques used today.

Inorganic arsenic (As) is a grey-appearing chemical element with the atomic number 33 on the atomic table. It is a metalloid meaning that it has both metallic and non-metallic properties. Its properties have long been used by humankind in a variety of ways such as a medicinal agent, a pigment and as a pesticide. Arsenic and its compounds are especially potent poisons and hence harmful to the environment and considered carcinogenic. Its toxicity to living things is due to the way it disrupts the function of enzymes involved in the energy cycle of living cells.

Does this then mean that our older taxidermy specimens containing arsenic are harmful in some way? Potentially yes if a specimen is damaged and the underside of the skin is exposed, but an intact specimen poses little risk provided sensible precautions are taken such as appropriate protective equipment when moving or conserving an affected specimens.

Besides, today most of the specimens we have on open display are preserved without the use of toxic chemicals, but such specimens are at greater risk of damage by insects. We thus monitor our collections to look out for the signs of insect infestation, and treat with safe and sustainable methods such as freezing if they occur.

But a good reason not to touch the specimens…..