Continuing the international year of the periodic table of chemical elements, for May we have selected lead. Everyone knows that lead is heavy, or more correctly dense, but did you know how important it was to the Roman Empire?

Mad, bad and dangerous to use – lead in Roman times

In Roman times lead was used extensively throughout the Empire. The chemical symbol for lead is Pb which comes from the Latin word for lead, plumbum, and is also the derivation of the word ‘plumbing’.

The extraction of lead ore is reasonably straightforward, and there was an abundant supply within the ever expanding empire. As well as being easy to find and one of the easiest metals to extract, lead is soft and malleable, has a relatively low melting point of 327.5°c (“low enough to melt in a camp fire”) and it is much denser and heavier than other common metals. It is also possible to cast it. This meant that it was widely produced and used for an enormous range of purposes from industrial to domestic.

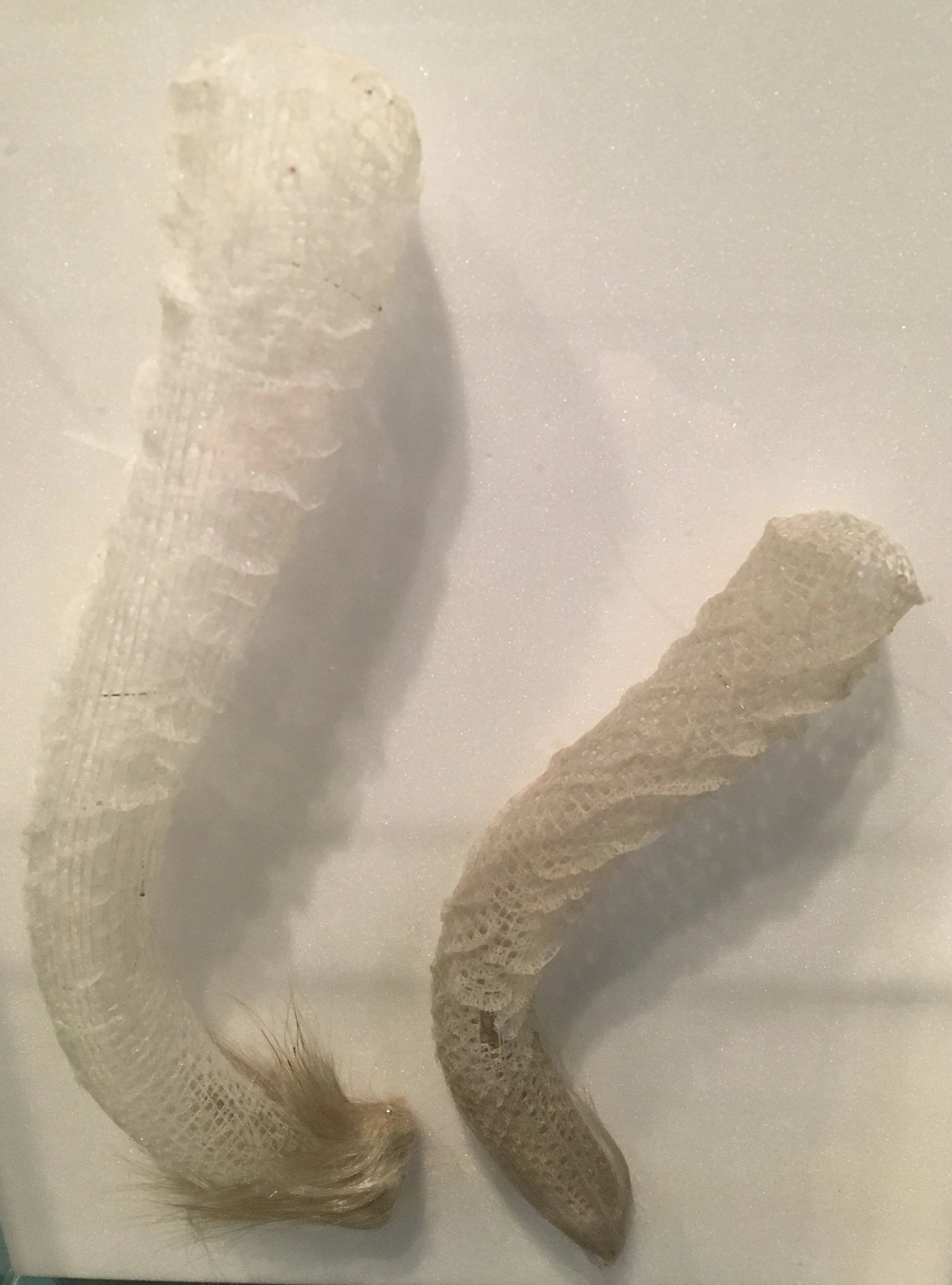

The Romans were famous for their plumbing systems, and as lead pipes replaced older constructions made of stone and wood, ever more elaborate plumbing systems could be created. In 2011 during the excavation undertaken by Cardiff University of the Southern Canabae at Caerleon an example of a lead water pipe was excavated close to the amphitheatre. It has a diameter of 0.12m, is bulged in the middle where two lengths of pipe have been joined using a wiped joint, and there are remains of a round collar pierced by iron nails at one end (to the left in the image) where it was probably attached to a wooden tank or pipe. As can be seen, the main pipe has been tapped by a narrower pipe and they were presumably used to feed a fountain or water feature within the large courtyard building found alongside.

The malleable nature of lead, and its relatively low melting point also made it very useful for soldering and repair work, for architectural fittings and for lining containers. It was even used as a type of Rawlplug. Its density made it ideal for weights and its abundance made it cheap enough to be used in a whole range of everyday objects, from a variety of containers, to lamps used to light Roman homes, luggage labels and stamps of all varieties. It was used in paint and in medicines and cosmetics and it was even used to sweeten and colour wine. Perhaps most important of all most ores of lead also contain a small quantity of silver and, in some instances the value of silver outweighed the value of lead. For an economy so dependent on silver this precious by-product was of great importance.

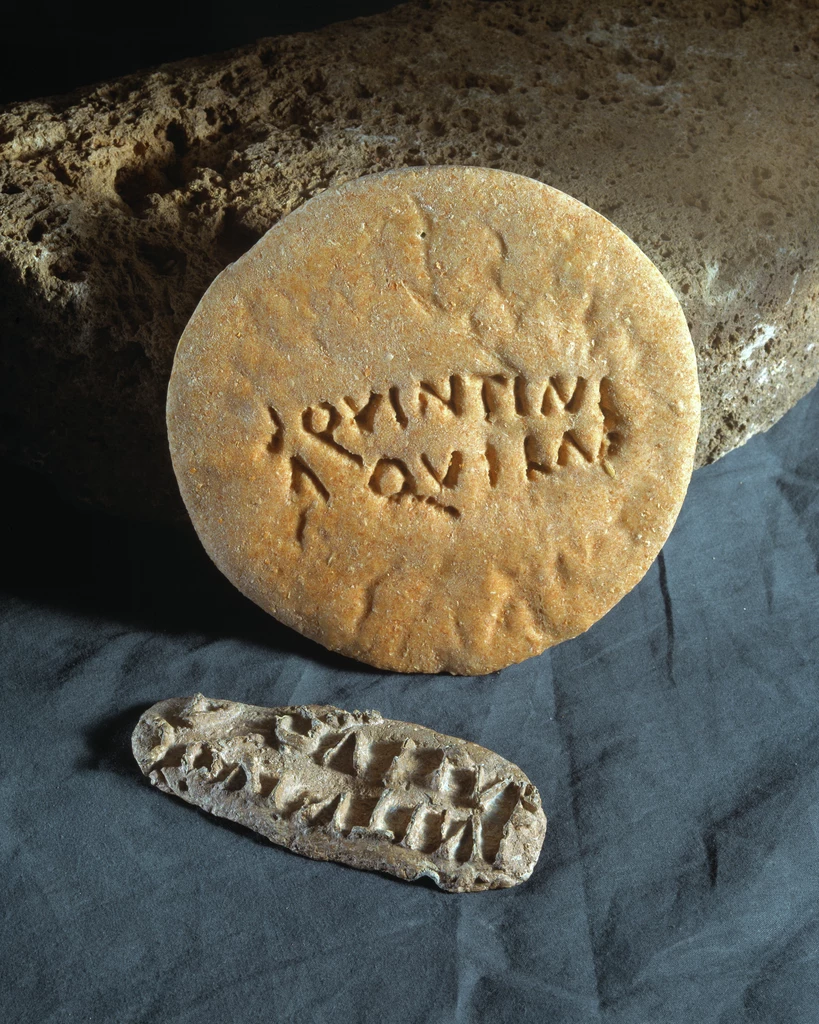

A perfect example of the everyday use of lead is the Roman lead bread stamp from Prysg Field in Caerleon (see the image on the right). Within the Fortress bread was baked in a communal oven and the bread stamps were used by each Company to clearly identify their bread ration for the day. The one in the photograph below was for the ‘Century of Quintinus’.

The simple lead lamp from Gelligaer near Caerphilly (shown on the right) illustrates a common form found on Roman sites – cheap and utilitarian. The main tray would have been filled with tallow (animal fat) and a wick would have extended to the raised area.

The wonderful curse tablet (shown on the right) found at Caerleon is the only such object so far recovered from Wales. It clearly illustrates the malleable and soft nature of the metal but also links to its cultural status as a ‘base’ metal. Scratched into the surface of the lead is a curse invoking the aid of the goddess Nemesis against a thief of a cloak and boots.

Research has shown that the letters of the inscriptions at Caerleon were painted exclusively using a red pigment called litharge (PbO), also known as red lead. Traces of red can still be seen on a stone inscription found at the Amphitheatre in Caerleon (shown on the right).

The heavy quality of lead meant that the Romans used it to make weights or to weigh things down. A Mediterranean style anchor stock from a small cargo ship was found just off the coast of the Llyn Peninsula at Porth Felen, Aberdaron.

The Romans cast the lead they mined into ingots known as ‘pigs’. Originally the lead mines in Britain were under the direct control of the Roman Authorities but this responsibility was later handed over to trusted local agents who leased the lead mines out to local companies on payment of a levy. A Roman lead pig found at Carmel in Whitford shows the insignia of one such agent, Gaius Nipius Ascanius. Other examples found in Britain have marks such as “EX ARG” (Ex argentariis), indicating that it was from a lead-silver works, or Deceangl[icum] indicating it was lead from the Deceanglic (Flintshire) region.

Lead in Roman Wales

According to Pliny, lead “is extracted with great labour in Spain and throughout the Gallic provinces; but in Britannia it is found in the upper stratum of the earth, in such abundance, that a law has been spontaneously made, prohibiting any one from working more than a certain quantity of it.” (Natural History, Book 34, Chapter 49)

Lead was so important to the Romans that they started extracting the ore almost as soon as they arrived in Britain. The Mendip area around Charterhouse in modern day Somerset was an important area for lead mining and evidence shows that mining began here as early as AD49. Originally mining was under the control of the Army, and in the Mendip Hills at this time that was the Second Augustan Legion. Their experience in overseeing the extraction of lead mines may well have proved useful when the Legion transferred to their new headquarters in Caerleon in AD74/5.

The area around Draethen woods near Lower Machen, contained lead ore reasonably high in silver content, certainly comparable to the Mendips and higher than any other lead ores to be found in South Wales. Draethen is just 10 miles away from Caerleon, about the same distance from the Roman fort at Gelligaer and even closer to the fort at Caerphilly. In 1937 work on the construction of a new bypass in Lower Machen uncovered evidence of Roman occupation, including evidence of a working floor with layers of charcoal and numerous pieces of lead and lumps of lead ore. Nash-Williams (Archaeologia Cambrensis, 1939) states that the early date of the pottery and coin finds suggest that Lower Machen “was certainly in Roman hands by the time of the completion of the Roman military conquest of South Wales in AD75, possibly before”. More recent discoveries of pottery also suggest an occupation period of c AD 70-100.

The 1965 exploration of ‘Roman Mine’ in Draethen throws more light on Roman lead mining in this area. In Roman times lead ore was extracted by laying wooden fires against the rock, heating the rock to a high temperature and then throwing cold water or vinegar onto it. This caused the rock to split into smaller pieces which could then be sorted by hand within the mine. The waste, known as ‘deads’, was packed into side chambers and empty crevices and the ore was brought to the surface on wooden trays or in leather sacks and wooden buckets. The evidence found within Roman Mine exactly matches this technique. Charcoal was found throughout the mine, even in the smaller tunnels, and the side chambers were filled with waste. The walls and roof of the tunnels were covered in a thick black patina caused by the production of an enormous amount of smoke. The creation of so much smoke also meant that the Romans had to sink shafts at regular intervals in order to create a through draft and the main passage of Roman Mine has many such outlets. No tools were found in Roman Mine but pick marks are frequent throughout the tunnels.

Who worked these mines? Nash-Williams (Archaeologia Cambrensis, 1939) presumes that the labourers who worked in Draethen were “slaves and convicts working under the supervision of a military guard, and the settlement would be under the control of an officer or government official.” It is likely that the lives of these miners were short and judging by the very small spaces of some of the worked areas within Roman mine it is possible that some of the labourers were children.

A detailed report on the lead mines in Draethen can be found here and more information about the objects found during the exploration of the mine can be found here.

Control of Substances Hazardous to Health (COSHH) - Lead poisoning in Roman times

Lead, despite all its many useful qualities, is also toxic. When ingested or inhaled, lead enters the bloodstream and inhibits the production of haemoglobin which is needed by red cells to carry oxygen. When lead levels in the blood increase it has a devastating effects on the body, including irreversible neurological damage. Children are particularly vulnerable because their tissue is softer and their brains are still developing.

Contemporary writing makes it clear that Romans were aware of the dangerous effects of lead and knew it could lead to insanity and death.

Pliny, in his Natural Histories, wrote about the noxious fumes that emanated from lead furnaces. Vitruvius in De Architectura suggests the use of earthen pipes to convey water because “that conveyed in lead must be injurious to the human system.” He goes on to note that “This may be verified by observing the workers in lead, who are of a pallid colour; for in casting lead, the fumes from it fixing on the different members, and daily burning them, destroy the vigour of the blood; water should therefore on no account be conducted in leaden pipes if we are desirous that it should be wholesome.” Celsus in De Medicina urges the use of rain water, conveyed through earthen pipes into a covered cistern.

However, although some advised against its use it was such a commonly used and important metal that it was almost impossible to manage without it. The vast majority of Romans probably remained unaware of the dangers and continued to use it in their everyday lives.

The study of lead levels in individuals from the Romano-British period is enabling researchers to gain a greater understanding of normal levels for different regions, and allows a growing degree of confidence in the identification of immigrants into an area. In complementary isotope studies the remains of the man found in the coffin at Caerleon showed lead concentrations of 4 parts per million (ppm), preserved in his teeth, which is typical of someone from the local area at this period.

Lead pollution in Ancient times.

The Romans’ extensive use of lead gives us a fascinating insight into the ups and downs of Roman history. In 2018 analysis of cores taken from Greenland’s ice sheet by the Norwegian Institute of Air Research showed that environmental pollution is not just a modern phenomenon. Pollution from lead mines can be traced in the layers of ice and clearly show the pollution left behind in ancient times. The researchers were able to use their measurements of lead pollution to track major historical events and trends. A clear pattern emerges where lead pollution drops during times of war, as fighting disrupts lead production. It then increases during periods of stability and prosperity. Lead pollution rose dramatically from the end of the Roman Republic and through the first 200 years of the Roman Empire, the Pax Romana. The measurements also starkly show the fall of this great Empire. The Antonine Plague struck in AD 165, a devastating pandemic that historians think was either smallpox or measles. Almost five million people died over the 15 years that the plague raged in the Empire, and whilst the Empire continued after the plague came to an end its economy never recovered. This is clearly shown in the low levels of lead in the ice layers during the years of the Plague and the centuries following it. The high lead emissions of the Pax Romana end at exactly the same time as the plague struck and do not reach those same levels again for more than 500 years.

More information about this fascinating research can be found here.

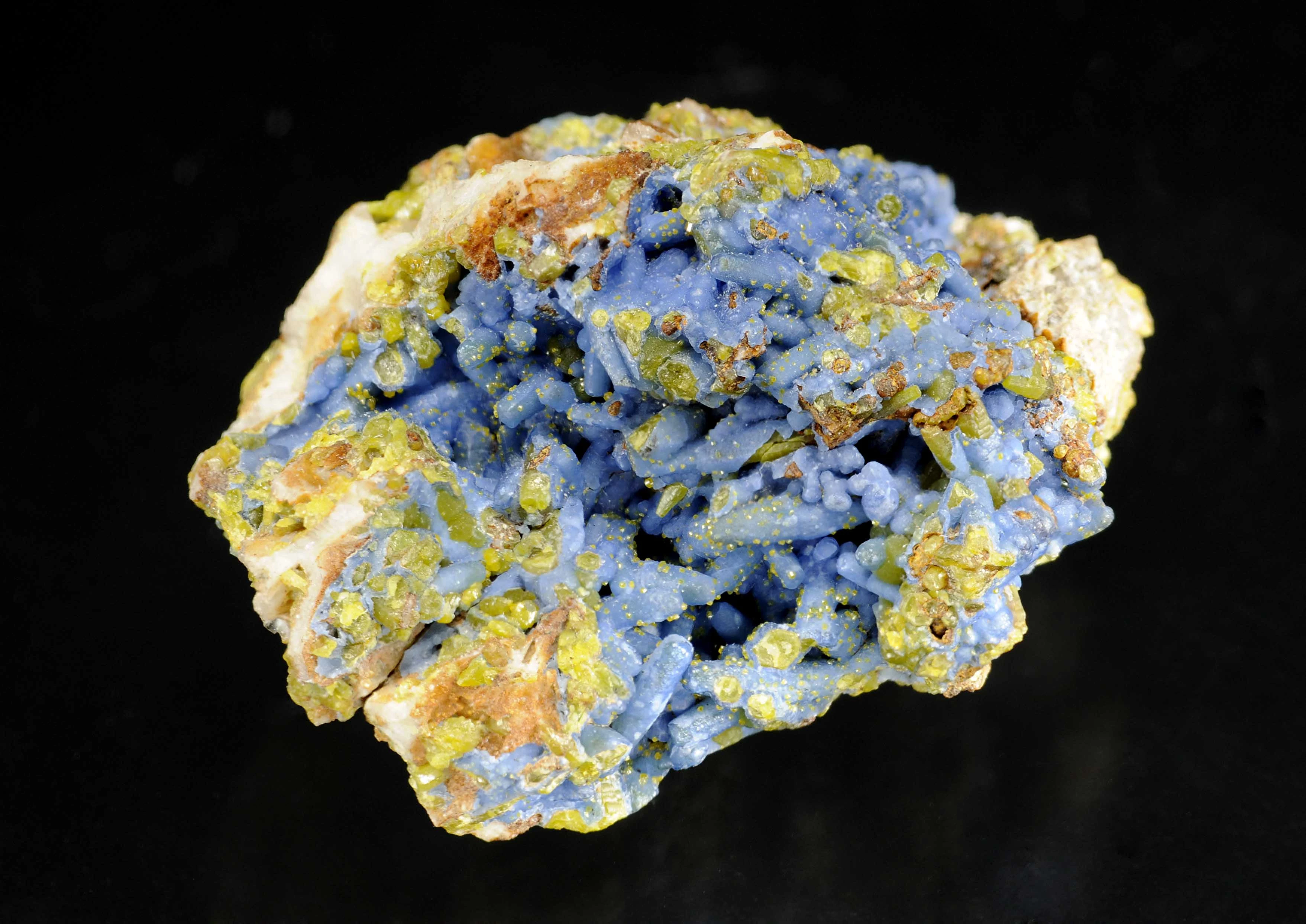

The museum’s geology collections contain many examples of lead ores from Wales and around the world including lead sulphide, or galena, the main ore of lead. Post-1845 (when official records started being kept) in excess of 1.2 Million tons of lead concentrate was produced from Welsh mines, but with a history of mining dating back to at least Roman times that figure should be considerably greater.

Natural weathering and oxidation of lead ores results in the formation of some beautifully coloured minerals. A few examples are illustrated here. It should also be noted that not all lead-bearing minerals are toxic – certain compounds containing lead are very stable. Experiments have shown that polluted mine dumps containing lead can be stabilised by oxidising some of the lead into phosphates such as pyromorphite or plumbogummite.