Volvelles: early paper calculators

, 19 July 2019

Cliciwch yma am fideo Cymraeg.

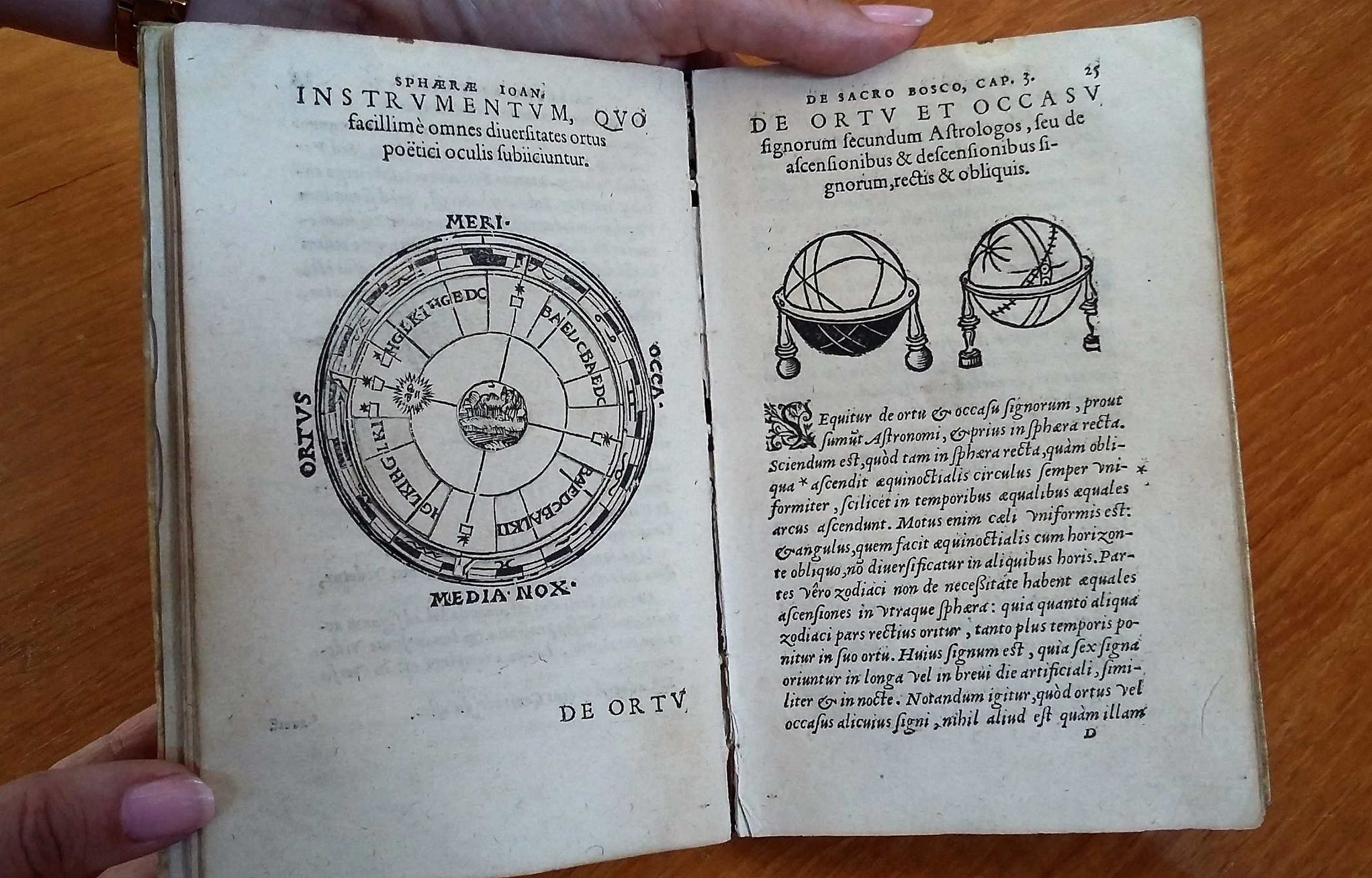

A volvelle is a rotating paper ‘wheel chart’, often found in early astronomy or mathematical books.

They were constructed from a number of circles, layered over each other, and fastened together in the centre with string so that they could spin. Volvelles were typically used to make calculations or predictions.

The design was based on astrolabes, very thin engraved metal discs that when rotated in various configurations made calculations, and were often employed as navigational devices. As astrolabes were quite costly to make, the paper versions were introduced as a cheaper alternative.

We believe that volvelles came to Europe from the Arabic world during the 11th and 12th centuries in medicinal and astronomical works. In the 16th century, books describing how to construct and use your own volvelle often came with printed sheets, so that the buyer could cut up and assemble their own.

We have a number of these types of books in our Vaynor Collection of astronomical books donated to the Museum in 1939 by John Herbert James of Vaynor Cottage, near Merthyr Tydfil. Some of these books still have their volvelles intact and working!

One example is a mid-16th century copy of The Sphere by Johannes de Sacrobosco. Johannes de Sacrobosco wrote Tractatus de Sphaera or De Sphaera Mundi, meaning On the Sphere of the World, in the thirteenth century when he was teaching at the University of Paris.

It remained a standard text for students of mathematics and astronomy for centuries, which is why we have this version from 1577, revised and expanded.

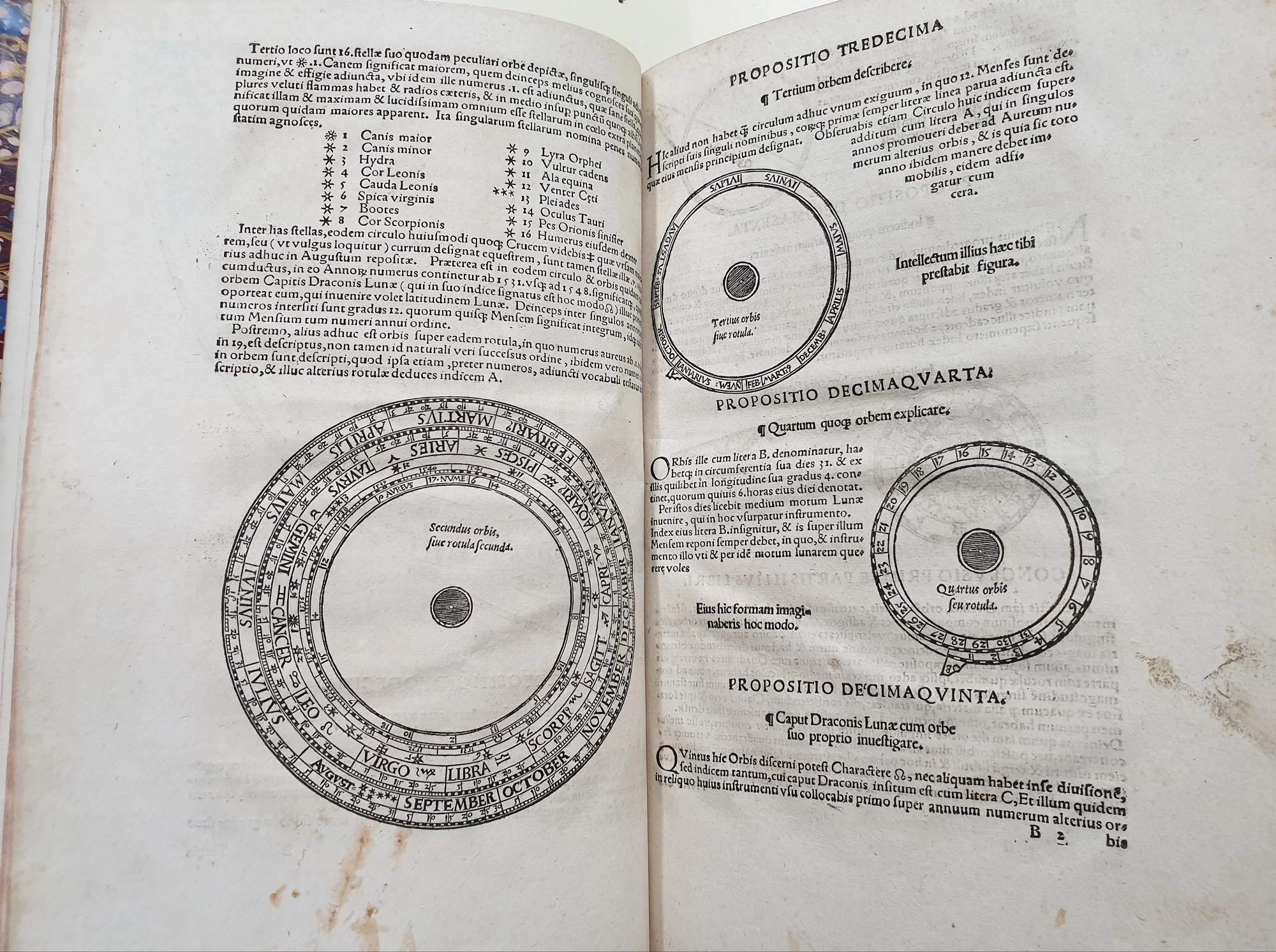

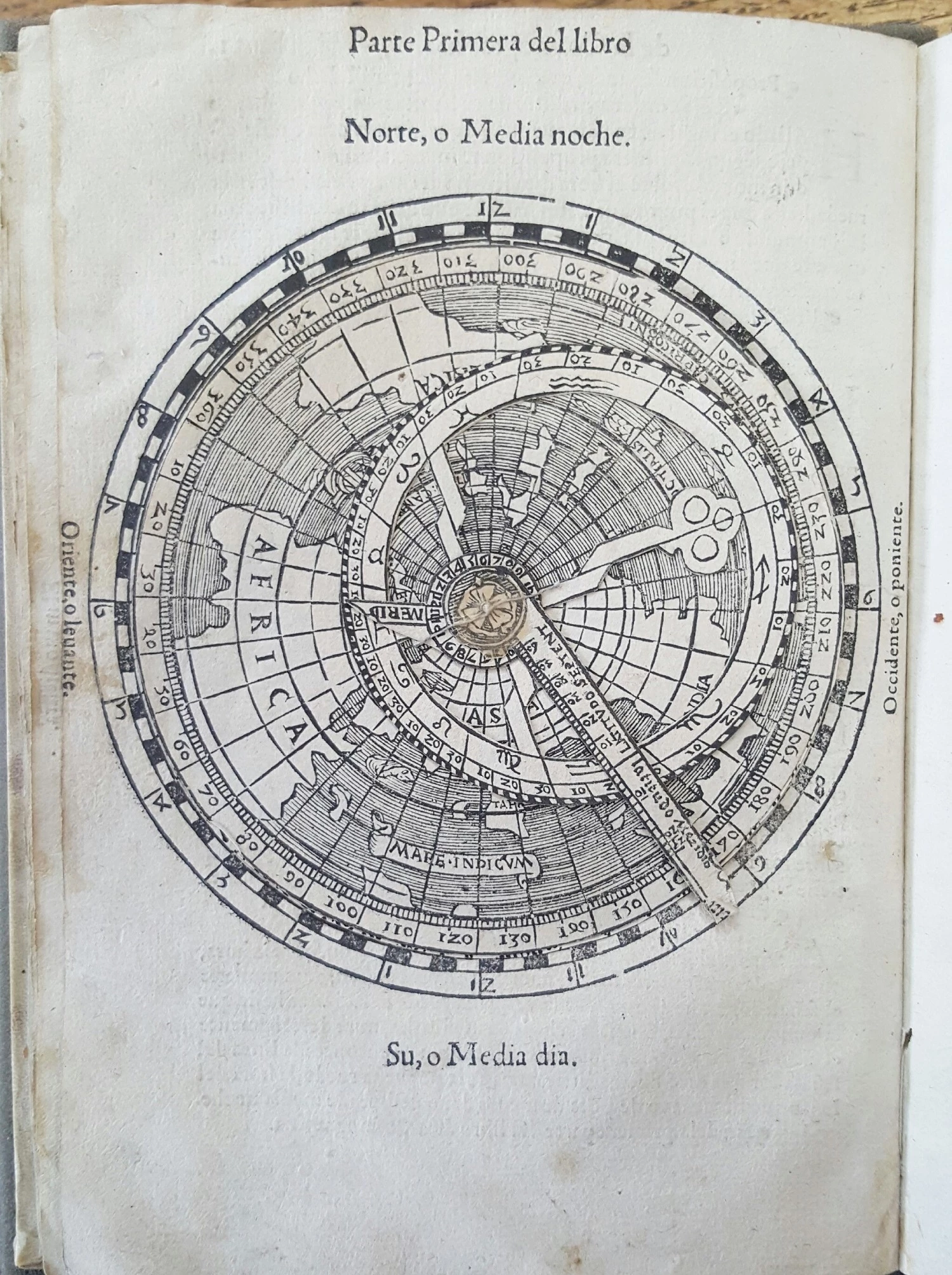

In 1548 Gemma Frisius produced his version of Peter Apian’s Cosmographia, a book which had originally been published in 1524, and was said to be one of the most popular books on cosmography ever published. Apian, more commonly known as Petrus Apianus, was a mathematician, designer of sundials, and publisher of manuals for astronomical instruments from his print shop in Ingolstadt, Bavaria. He was well known for his volvelles designs which is why they are sometimes also known as "Apian wheels", and this edition of Cosmographia features a number of them, although they are in a very fragile state.

However, in a few of our Vaynor books, the owner never got around to assembling the volvelles, and instead the printed sheets were bound in at the back of the book like regular pages.

This book Quadrans Apiani astronomicus... from 1532 is also by Peter Apian, and explains the use of quadrants, scientific instruments for measuring angles or time, derived from astrolabes, and used very much by sailors for navigation.

Our copy contains printed sheets for the construction of a volvelle, all the separate sections can be cut out and then assembled. The largest piece would serve as the base, and then all the corresponding circles would all be stacked up on top of each other in order, until the smallest was on the top. Then the whole thing would be secured through the middle with string.

We’ve reproduced a set from the Quadrans book, so have a go at constructing your own volvelle by downloading and printing this worksheet . You can use a split pin to secure the circles instead of string!