The Lost Treasures of Swansea Bay

, 14 October 2016

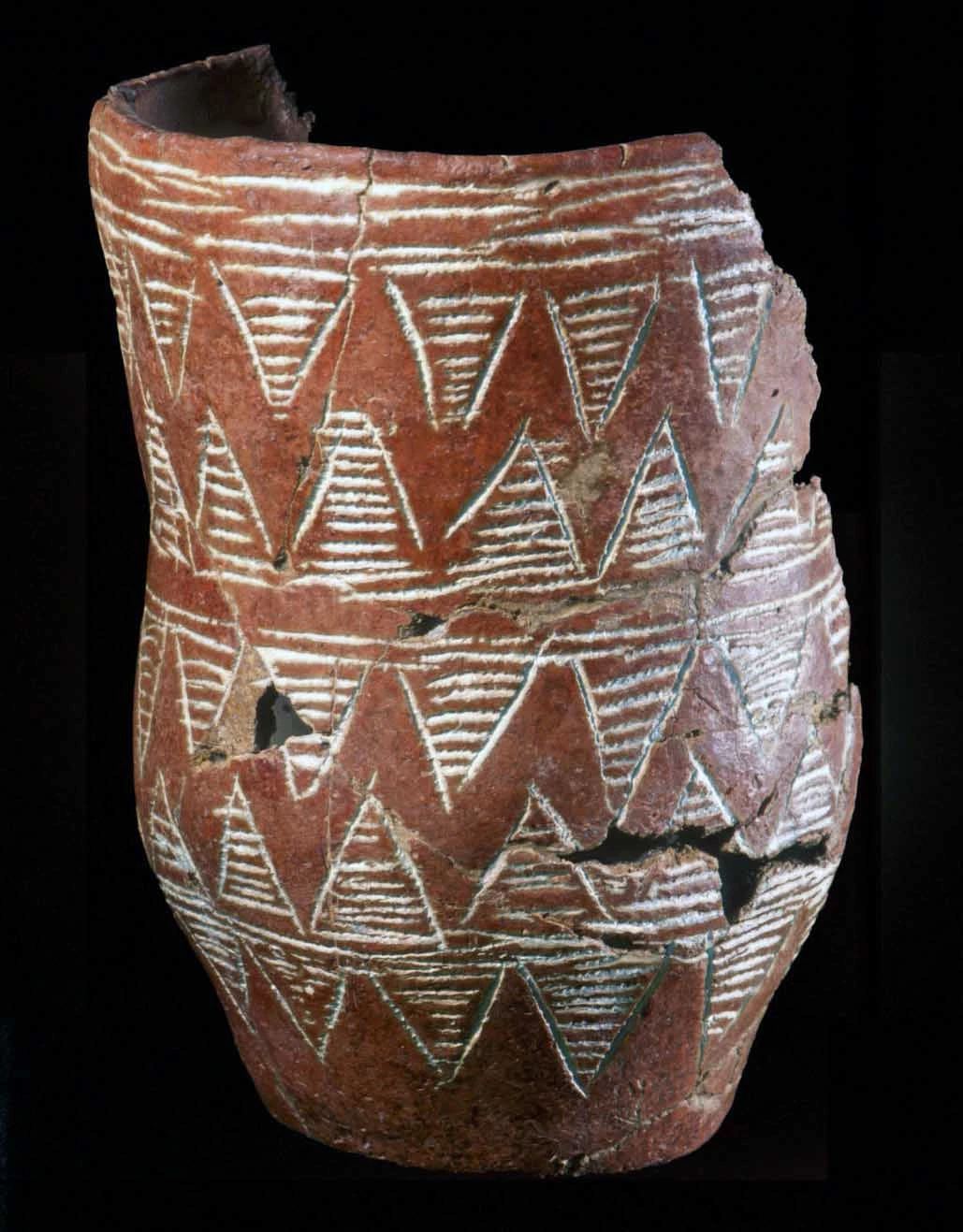

‘The Lost Treasures of Swansea Bay’ is the first Community Archaeology project funded by the HLF project Saving Treasures, Telling Stories. Run by Swansea Museum, the project is inspired by a collection of finds made by a local metal detectorist on Swansea Bay, which has also been acquired for the museum by Saving Treasures.

Blades and Badges

It includes some mysterious items, such as a Bronze Age tool with a curved blade which has had archaeologists scratching their heads. Ideas about its purpose range from opening shellfish to scraping seaweed off nets or rocks or carving bowls.

Among the other items found on the Bay are a number of medieval pilgrim badges, including one brought back from the important shrine of Thomas Becket at Canterbury. Pilgrim badges are usually made of lead or pewter and were often bought at shrines as a souvenir and worn on the pilgrim’s hat or cloak.

It is thought that those found in Swansea Bay were probably thrown into the sea by pilgrims returning to south Wales by boat as a thanks offering for their safe return. It seems like a curiously pagan thing for a medieval Christian to do, but it’s similar to the modern practice of throwing coins in wells, which is itself a survival of an ancient religious ritual.

The Archaeology of the Bay

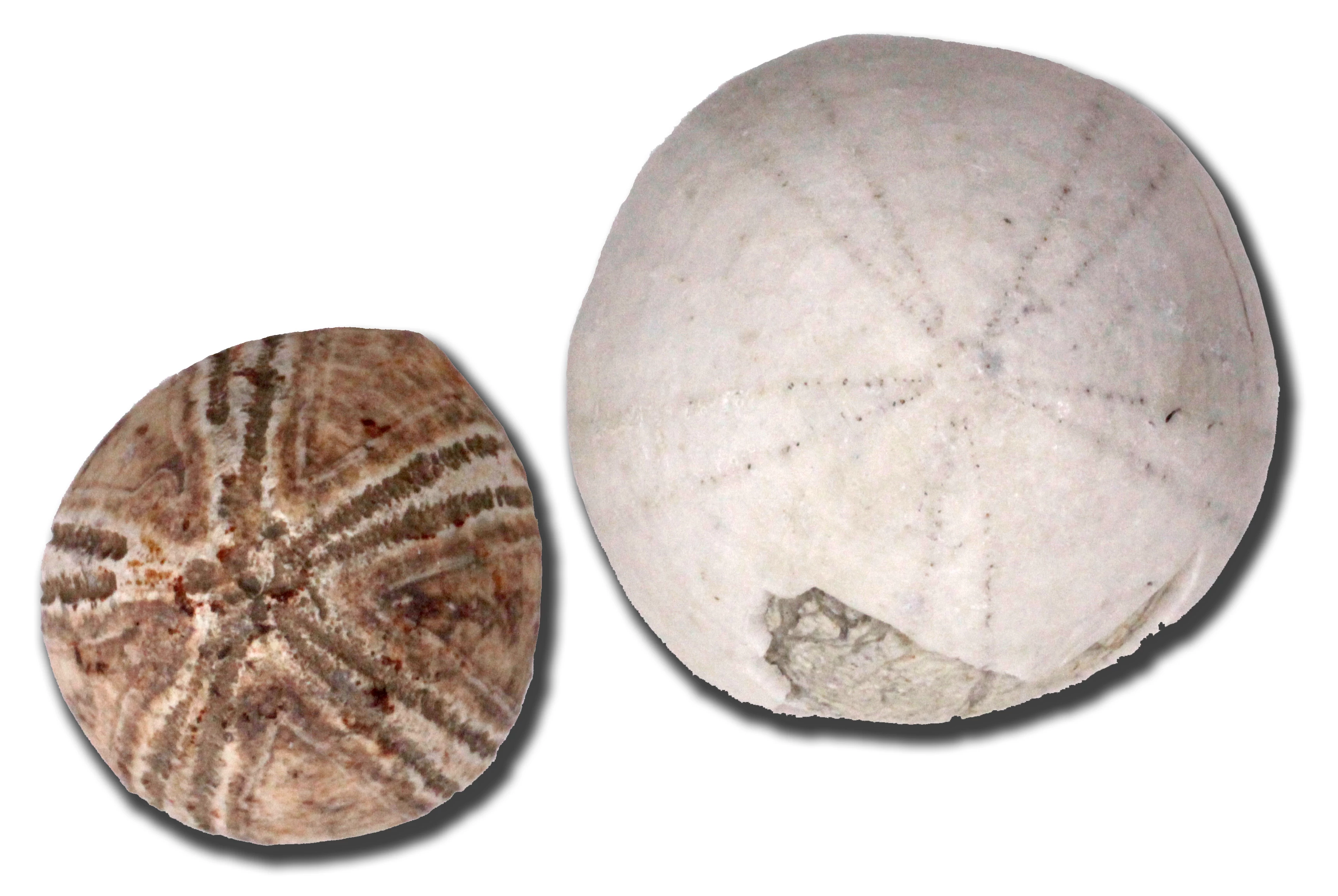

The new collection is just a tiny fraction of the objects discovered on the Bay, which has a rich and varied – as well as sensitive – archaeology. This includes fragments of Bronze Age trackways and prehistoric forests, Roman brooches, ceramics, shipwrecks and the remains of World War Two bombs.

Community Involvement

Each one has a tale to tell and together they are helping archaeologists build the story of human activity in the Bay over thousands of years. Helping to interpret the finds, their significance for the history of Swansea Bay and for the people of modern Swansea are representatives from Swansea community groups, including the Red Café youth group, the Dylan Thomas Centre’s Young Writers Squad, Community First families and the Young Archaeologists Club.

The project’s first activity, a Big Beachcomb, took place on the Bay itself on Saturday 17 September, but to find out about that you will have to wait for the next blog in this series…