Women in Archaeology

, 10 March 2016

Women's History Month is deeply rooted in the suffrage movement of the late 19th and early 20th centuries. To highlight the need for equality, it was vital to show the contributions that women had made throughout history and continued to make in current times. In celebration of Women's History Month, and in conjunction with Treasures: Adventures in Archaeology, we take a look at some of the women who helped shape the discipline of archaeology.

Gertrude Bell was born in County Durham in 1868. She was educated at home and went on the attend Oxford University where she earned a degree in history. During a trip to Iran, she fell in love with the history and culture of the Middle East. Becoming fluent in Arabic and Persian, she travelled extensively throughout the region, many times to places few Europeans had ever been. During her trips, she would also carry out archaeological surveys of ruins and published several books. Because of her unparalleled knowledge of the Middle East, when the First World War began she took a job with British Intelligence in the Arab Bureau in Cairo. While there she worked with fellow adventurer and archaeologist T.E. Lawrence (Lawrence of Arabia). In the post war years Bell became deeply involved in the formation of Iraq and Jordan as independent nations. She had a close relationship with King Faisal of Iraq and Syria and in 1922 the new government appointed her Director of Antiquities. In this role, Bell became a passionate supporter of artefacts remaining in their original countries, not in European collections, and to combat this she wrote the Laws of Excavation, which gave protection to archaeological sites in Iraq, and established the National Museum of Iraq in Baghdad. Recently a movie, Queen of the Desert, was made of Bell’s life starring Nicole Kidman.

1939 excavation of Sutton Hoo burial ship by Harold John Phillips

Tessa (Verney) Wheeler was born in Johannesburg in 1893. The family relocated to England and Tessa read history at University College London. While there she met her future husband, Mortimer Wheeler, who would become a preeminent archaeologist. After graduating, Tessa move to Cardiff where her husband had taken up the position of Keeper of Archaeology at the National Museum of Wales. During their time there, Tessa and Mortimer carried out extensive excavations at Roman sites such as Segontium (Caernarfon) and Y Gaer (Brecon). Just as they were preparing to begin excavating at Caerleon, Mortimer was appointed Keeper at the London Museum. Instead of abandoning the project, Tessa took over the excavation. Early in her career she was often overshadowed by her husband but in later life she was recognised for her fieldwork and the contributions she made to the ‘Wheeler team’. Tessa Wheeler at Caerleon amphitheatre

Turkish archaeologist Halet Çambel was a woman of many talents. Born in Berlin in 1916, she had taken up fencing as a child and became the first Muslim woman to compete in the Olympics as part of the 1936 Turkish fencing team. She famously declined an invitation to meet Adolph Hitler. She then attended the Sorbonne in Paris where she read archaeology and the languages of Hittite, Assyrian and Hebrew. She spent most of her career excavating in Turkey and spent over 50 years working at Karatepe, a Hittite stronghold. She created the department of Prehistoric Archaeology at Istanbul University and in 2004 was awarded the Prince Claus Award, which is presented to those “whose cultural actions have a positive impact on the development of their societies.”

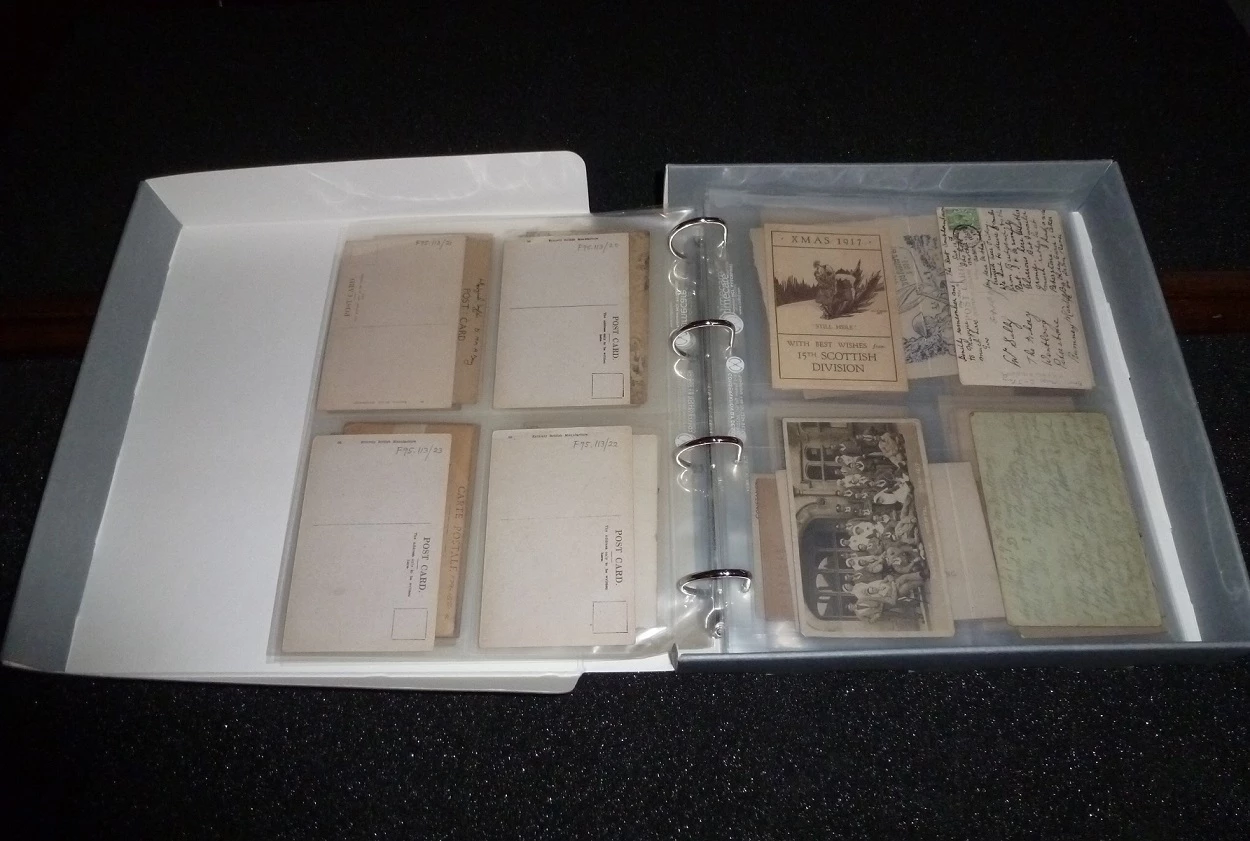

A person doesn’t have to be a trained expert to have an impact on archaeology. Take for example, Edith Pretty. Born in 1883, Edith’s family saw the value in education, especially education via travel. Throughout her many travels, she was able to see archaeological excavations in progress. Her father also had an interest in archaeology and was given permission to excavate a Cistercian Abbey near their home in Cheshire. Having inherited money, she bought land in Suffolk and moved there with her husband. The property held several burial mounds which did not appear to have been excavated. Edith and her husband often wondered what may lie beneath the mounds but Edith wanted any excavations to be done using the most up to date scientific methods. In 1937, she contacted the Ipswich Museum and requested the mounds be excavated. Two years later, the largest of the mounds produced one of the most important archaeological finds, the Sutton Hoo burial. She gifted the finds to the British Museum where they are on display. 1939 excavation of Sutton Hoo burial ship by Harold John Phillips

These are but a few of the women who have contributed to archaeology. For more information, please visit http://trowelblazers.com/