Amgueddfa Cymru showcases new technology for visitors

, 8 August 2018

A technology first for UK museum

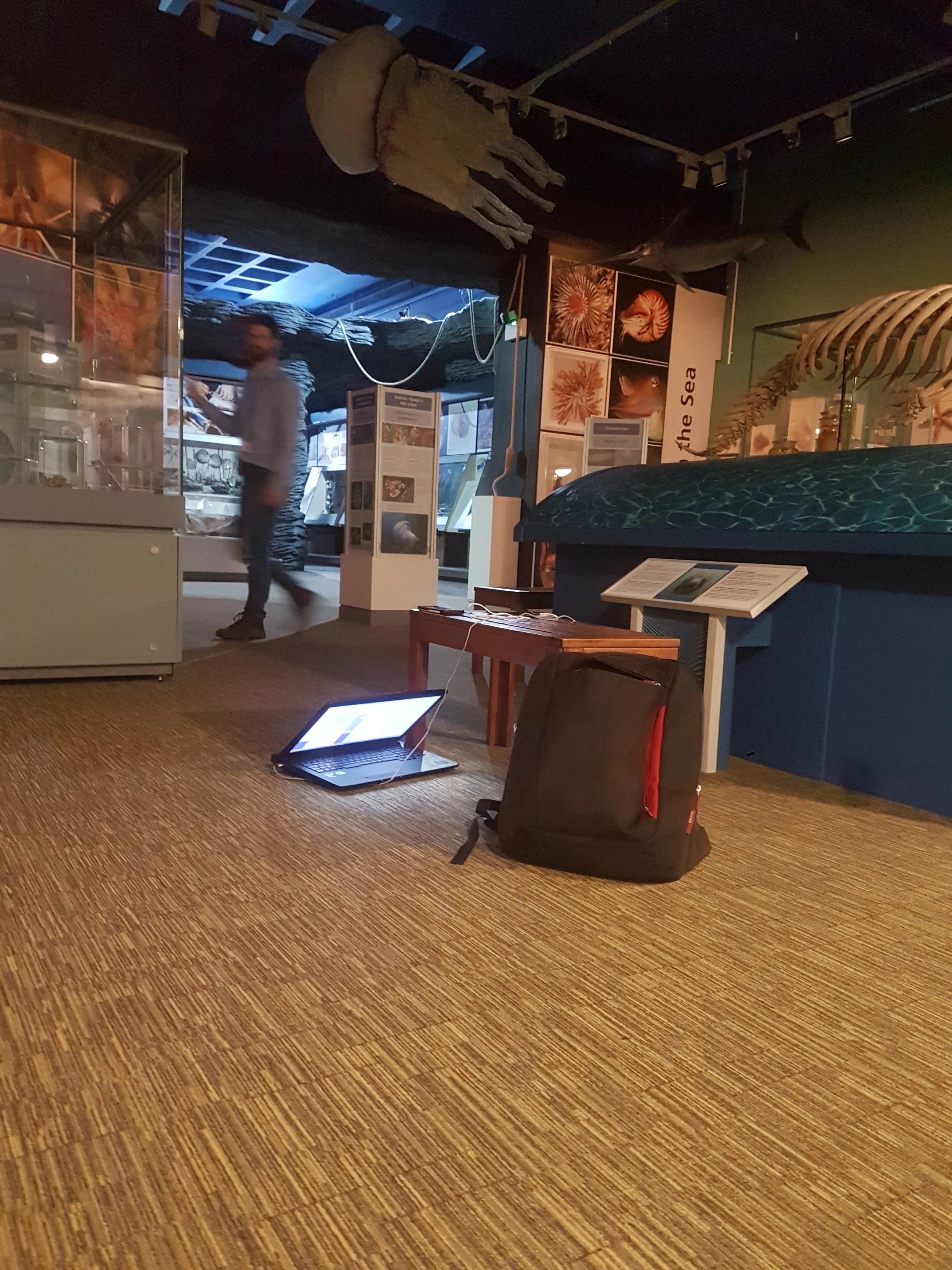

This week sees the launch of

Museum ExplorAR; a brand new experience at National Museum Cardiff, bringing some state-of-the-art (and never seen before) technology into our galleries allowing you to witness our spaces as never before.

Using a handheld device available to hire from the shop you can explore the following self-led experiences:

-

Underwater life: See our collection of sea creatures come to life in the Marine Gallery, be awed by our humpback whale as it would have looked swimming in the ocean... but watch out for the shark!

-

Monet’s Waterlily Garden: Explore the inspiration for Monet’s waterlilies in our Impressionist Gallery. Look out for Monet, and the Davies Sister who collected most of what you see in the gallery.

-

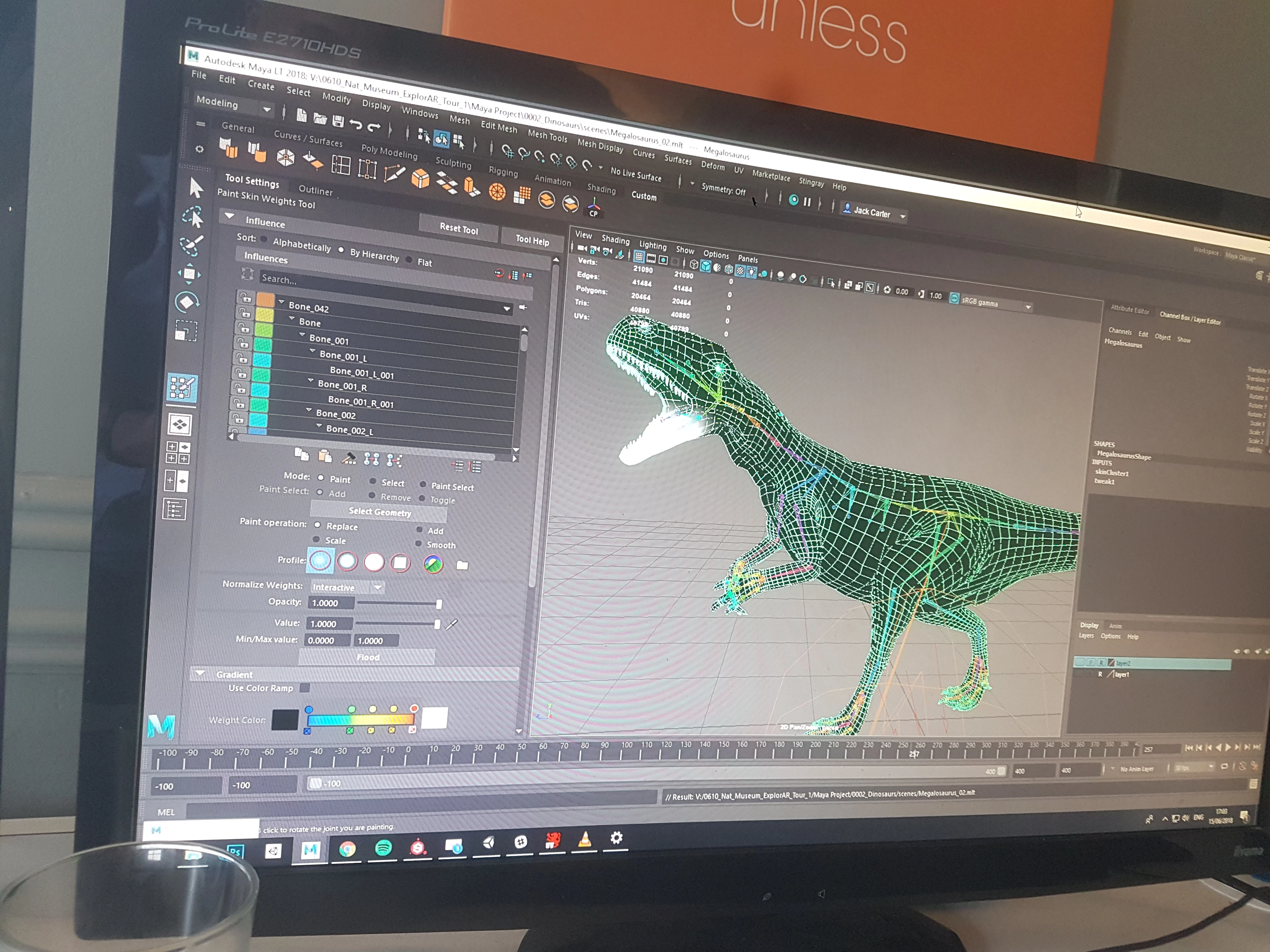

Dinosaurs and Prehistoric Creatures: Discover the lives of dinosaurs from 220 million years ago; see their skeletons brought to life and swim with the prehistoric creatures that once swam in our seas.

The project has been developed as a pilot in order for us to evaluate how we best approach and employ new and emerging technologies in our Museum spaces. Our permanent galleries may have been static for some years, but augmented reality can offer new and exciting opportunities to refresh narratives and explore new storylines in our Museums.

At this stage, we envision the devices to be available for hire for about 20 weeks over which time we will be evaluating popularity, ease of use, navigation, interpretative approach and overall enjoyment. A huge bonus of the system is despite the experiences offering a geographically aware tour, there is no requirement for any connectivity or data transfer requirements (i.e. we are not dependant on WiFi or networks), overcoming many connectivity obstacles in a complex and busy public space.

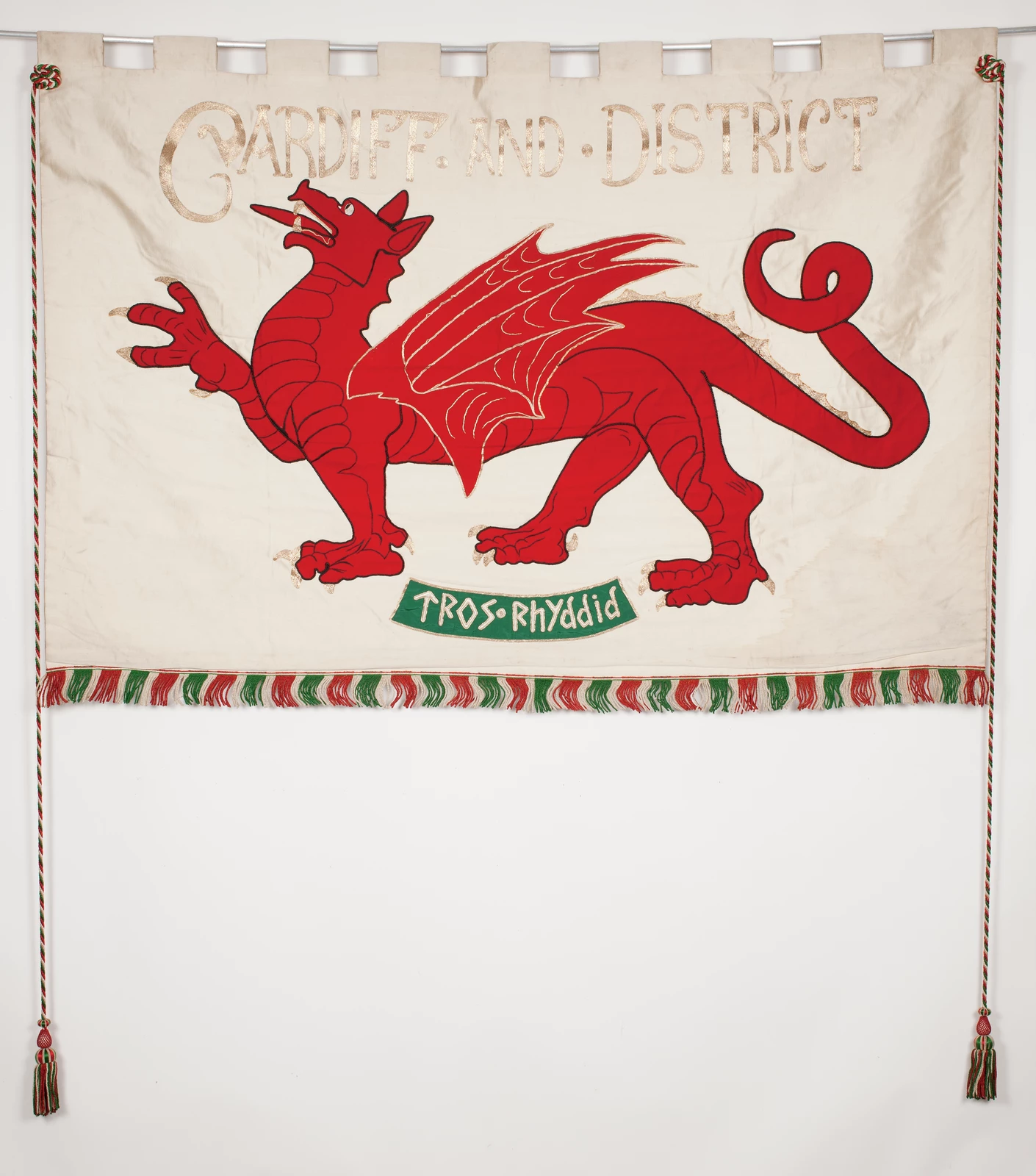

As this coincides with our

Kizunaexhibition, Museum ExplorAR is available for you in three languages: Welsh, English and Japanese.

Top of the range graphics

The experience has been developed by Jam Creative Studios, an innovative, creative agency based in Cowbridge, south Wales. Thanks to their hard work and hours of dedication, they have delivered us a superb (yes, I am biased) new technology that offers a perfect synergy between exhibition interpretation and amazing jaw-dropping graphics and effects. They have come up with new and novel ways to showcase some of our most difficult-to-interpret collections - for instance our pavement of dinosaur footprints from south Wales where most visitors are unable to make sense of the plethora of footprints going in all different directions. Jam Creative Studios have skilfully isolated and superimposed these dinosaur trackways for us to be able to witness clearly the marks made by these extinct creatures.

What is Augmented Reality (AR)

AR, or Augmented Reality allows people to use (typically) a handheld device to view superimposed content onto the scene before them. The benefits of this technology is that you are able to experience the effects only when looking at the screen you are holding, thus still being able to interact fully with the real world around you. You may have heard of VR (Virtual Reality) which is a technology that is completely immersive and requires a full headset, cut off from the real world. We have chosen augmented reality, obviously as our visitors are walking around the gallery, we don’t want them blind to their surroundings, or each other!

This approach also means families or groups can share the experience together, something initial feedback confirms

Amgueddfa Cymru are proud to be the first place to showcase this augmented reality technology.

The system uses a combination of area learning with augmented reality. Essentially it means that, rather than having to rely on traditional AR triggering methods (such as image tracking within your camera view or markerless AR-which requires the user to place their own virtual content within a scene) the ExplorAR can tell exactly where the user is within the gallery and can trigger appropriate content accordingly. This makes for a much more immersive experience giving users the freedom to explore all around the virtual content with no restrictions. It’s also really intuitive to use.

Testing and Evaluation

Evaluation will be key factor of the pilot, with a survey built in at the end of each tour. In addition to qualitative evaluation, this technology allows for detailed analytics on its usage, including such things as: Visitor flow, dwell time for each exhibit, most popular exhibits and average visit duration.

We will test and seek comprehensive feedback with a variety of users and groups, with advice from the Learning Department to gain feedback on content approach and overall concept design. We will also review our internal workflows and lessons learnt from delivering such a project, helping build a knowledge base for the organisation on best practices for future technologies we may wish to implement.

This is just the beginning...

The launch of Museum ExplorAR is the start of our investigations into how best we employ technology into our public spaces. We will be using visitor feedback to analyse where we go from here, of course the possibilities are endless, so before we go any further we need first hand accounts of what you, our visitors like, want, and expect, before we develop anything further.

Come and give it a go and let us know what you think, but remember, you saw it here first!

Plan your visit