Imagine a Castle: The problem of castles in Wales?

18 February 2020

The current display Imagine a Castle: Paintings from the National Gallery, London offers a great opportunity to see a selection of European Old Master paintings for the first time in Wales alongside Amgueddfa Cymru – National Museum Wales’s own collection.

Comparing European and Welsh castles and the history and legends that come with them plays a vital part in defining Welsh cultural identity. Yet the history of castles in Wales is, for some, contentious.

To find out why we need to go back to the thriteenth century. During this time, there were many disputes between Welsh princes and English kings. Llywelyn ap Gruffudd (last Prince of Wales) was involved in many disputes with Edward I, who launched a vicious campaign on the Welsh. This resulted in Llywelyn losing his power, land, titles and ultimately his life.

Following this English victory, Edward began the most ambitious castle-building policy ever seen in Europe. His collection of fortresses became known as the infamous ‘iron ring’ and included those at Harlech, Caernarfon and Conwy. They were intended to intimidate the Welsh and subdue uprisings. Along with these English-built fortresses came new towns that were intentionally populated with English settlers. Welsh people were forbidden to trade or sometimes even enter into the towns’ walls. Yet, while these castles remind us of English power over the Welsh, the strength of their construction underlines that Edward was conscious of the formidable and ever-present threat of Welsh resistance.

To acknowledge the histories of castles in Wales, we have included works from two Welsh artists, the ‘father of British landscape painting’, Richard Wilson, whose works offer an eighteenth-century perspective, and contemporary artist Peter Finnemore.

Wilson’s work reflects his travels to Italy and the influence of the hugely important French landscape painter, Claude Lorrain, whose work can also be seen in this exhibition. Wilson painted many Welsh landscapes and is recognised as changing the face of British landscape painting. While his work encouraged artists to come to Wales, many of his later Welsh compositions, such as Caernarfon Castle (Edward’s main seat in Wales) remind us more of the warmer climates of Italy. As such, they also point to his inspirations outside of Wales.

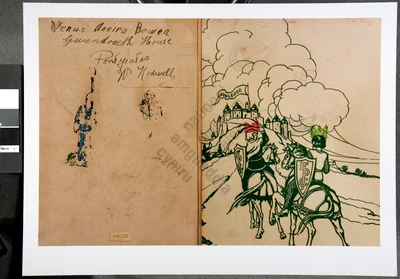

On the other hand, Finnemore’s photographic works, Lesson 56 – Wales and Ancient Ruler Worship (made especially for this display), look at castles in Wales from a more recent Welsh perspective. Finnemore’s work revolves around his Welsh-speaking grandmother’s school textbooks that were written from an English standpoint. Her childhood drawings in these books humorously undermine the didactic English text. Ancient Ruler Worship depicts Castell Carreg Cennen and looks back to World War II. It is taken from a still in Humphry Jennings’s propaganda film, Silent Village, that portrayed this castle as a site of Welsh resistance during an imagined Nazi invasion. The film demonstrated solidarity with Lidice, a mining village in the Czech Republic that was totally destroyed by the Nazis.

Whatever we may feel about their history, many of Edward’s Welsh castles are now designated as UNESCO World Heritage sites. Edward left a unique and internationally important legacy of medieval military architecture that can only be seen in Wales.