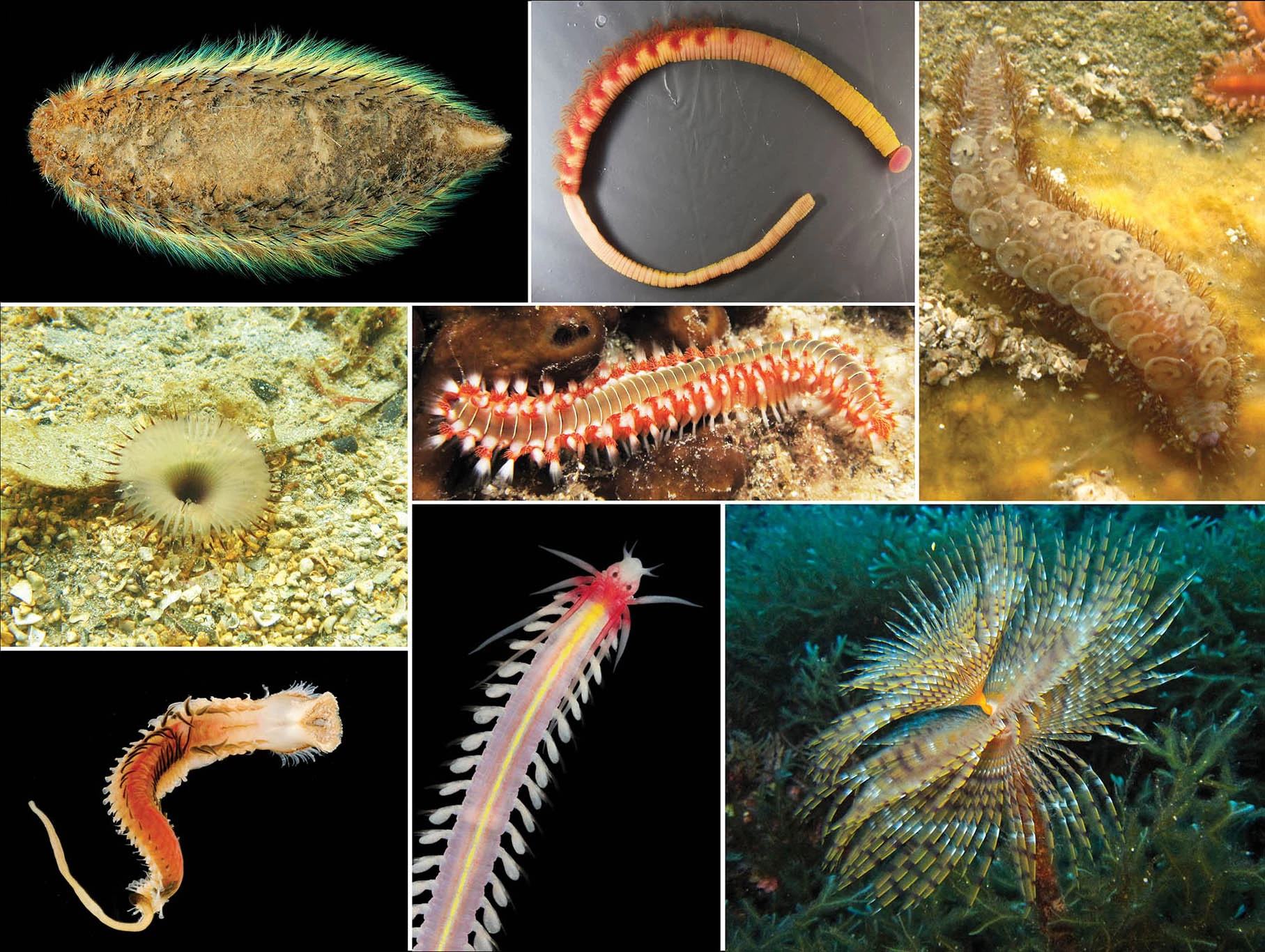

"If you asked me what a magelonid was 18 months ago, I would have looked at you with a somewhat muddled expression. Let me tell you, a lot has changed since then. Roll onto the present day, after a year at Amgueddfa Cymru – National Museum Wales for my Professional Training Year (as part of my Zoology degree at Cardiff University), I could talk for as long as you are willing to listen about this fascinating family of marine bristle worms, commonly known as the shovel-head worms (Annelida: Magelonidae)."

When my application was first approved from the Natural Sciences Department at the museum, I didn’t know what to expect. I had always loved anything marine and knew from the start this is the area I wanted to build a career around. This was a very broad declaration and beyond this, I was rather diffident in what I wanted to pursue. Therefore, my number one priority was to keep an open mind and make the most of everything the experience would offer. This view shaped a year filled with opportunities, that has not only been indispensable in developing my scientific skills in both hands on research and writing, but also in giving me a direction I am interested in for the future.

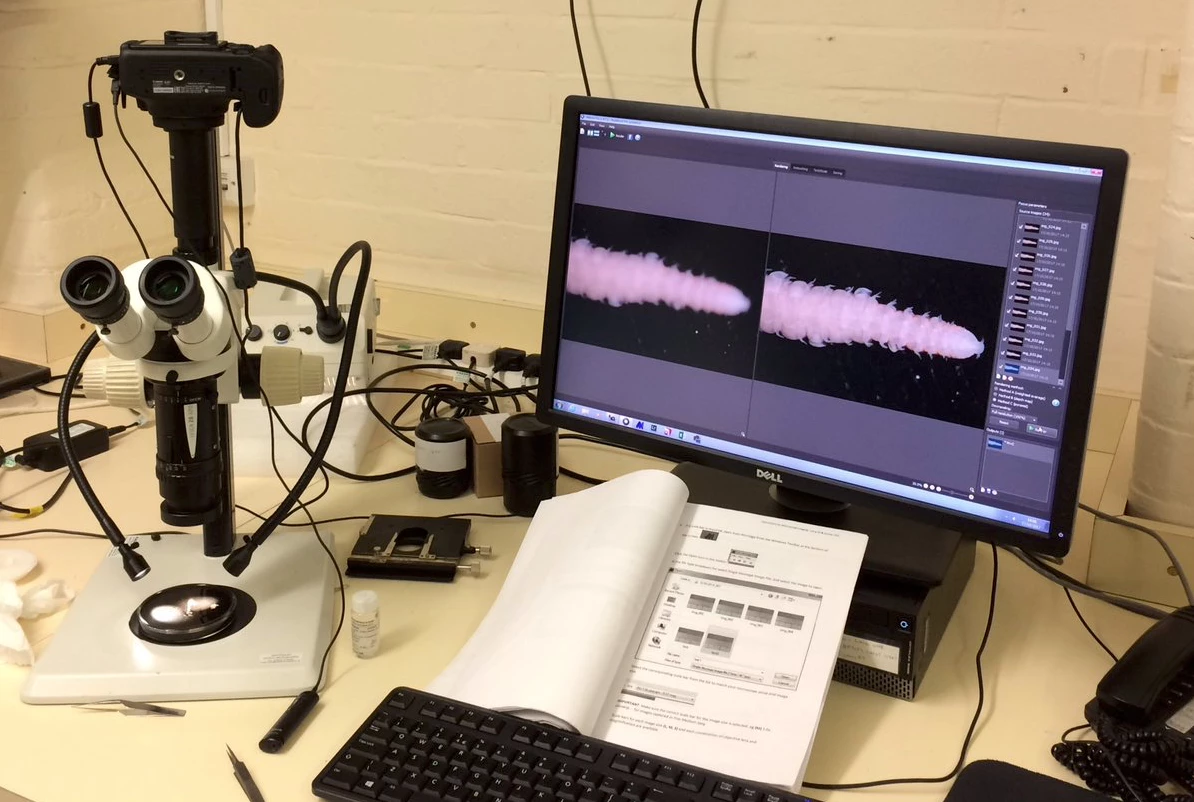

The majority of the placement involved both behavioural and taxonomic studies on European magelonid species, through the practicing of methods such as time-lapse photography, live observation, scanning electron microscopy, high definition photography using a macroscope, and taxonomic drawings using a camera lucida attached to a microscope. As a result of this work, some very interesting findings were highlighted for the Magelonidae, with important implications for furthering our understanding of these enigmatic animals. Perhaps the most fascinating arose through extensive time-lapse photography and observing animals in aquaria within the marine laboratory, in which an un-described behaviour emerged in the tube dwelling species Magelona alleni. Later termed as ‘sand expulsion’, this behaviour was a highly conspicuous method of defecation where M. alleni would turn around in a burrow network, raise its posterior region into the water column and excrete sand around the tank. Just knowing I was most likely the first person to ever witness this was a very rewarding experience in itself! To understand why this novel behaviour was exhibited, the posterior morphology of M. alleni was compared to additional European species. These findings have led onto my first publication in a peer-reviewed journal, of which two more papers and an article are due to follow as a result of working closely with my supervisor throughout the year.

I also got the opportunity to participate in tasks that are essential to the upkeep of the museum, such as curation, specimen fixation and preservation, along with invertebrate tank maintenance. Additionally, I participated in sampling trips, including a visit to Berwick-upon-Tweed and outreach events, such as ‘After Dark at the Museum’, which saw over 2,000 visitors, and the RHS show Cardiff.

Overall, the museum is a very friendly, intellectual and dynamic environment that has more to offer than perhaps meets the eye. This is why anyone who wants to study the small, whacky and wonderful world of marine invertebrates should not pass up an opportunity to undertake a placement here. Spend any prolonged amount of time amongst the hundreds of thousands of specimens kept in the fluid store, and I guarantee you will not be able to escape a visceral appreciation of the natural history of our world. With this comes a feeling of preservation for all we have and a reinforcement of why museums are such a crucial component of our society today, something that is too easily forgotten.

Read more about Kim's journey through her PTY Placement at National Museum Cardiff:

https://museum.wales/blog/2017-08-04/A-new-world-of-worms---beginning-a-Professional-Training-Year-at-the-museum/

https://museum.wales/blog/2017-11-15/A-tail-of-a-PTY-student/

https://museum.wales/blog/2018-02-07/The-early-bird-catches-the-worm/