Analytical chemistry in the museum

, 24 November 2016

This week is Chemistry Week and our Preventive Conservation team got involved. Two local high schools (St Teilo’s Church in Wales High School and Cardiff High School) were invited to participate in a workshop with live demonstrations and hands-on activities.

We organized the workshop in a collection store and one of our analytical laboratories at National Museum Cardiff. Neither space is laid out for large numbers of people and it’s always a bit of a squash. But once we had squeezed the last of the year 12 and 13 students into each room and closed the doors, there was no escaping the exciting world of analytical chemistry.

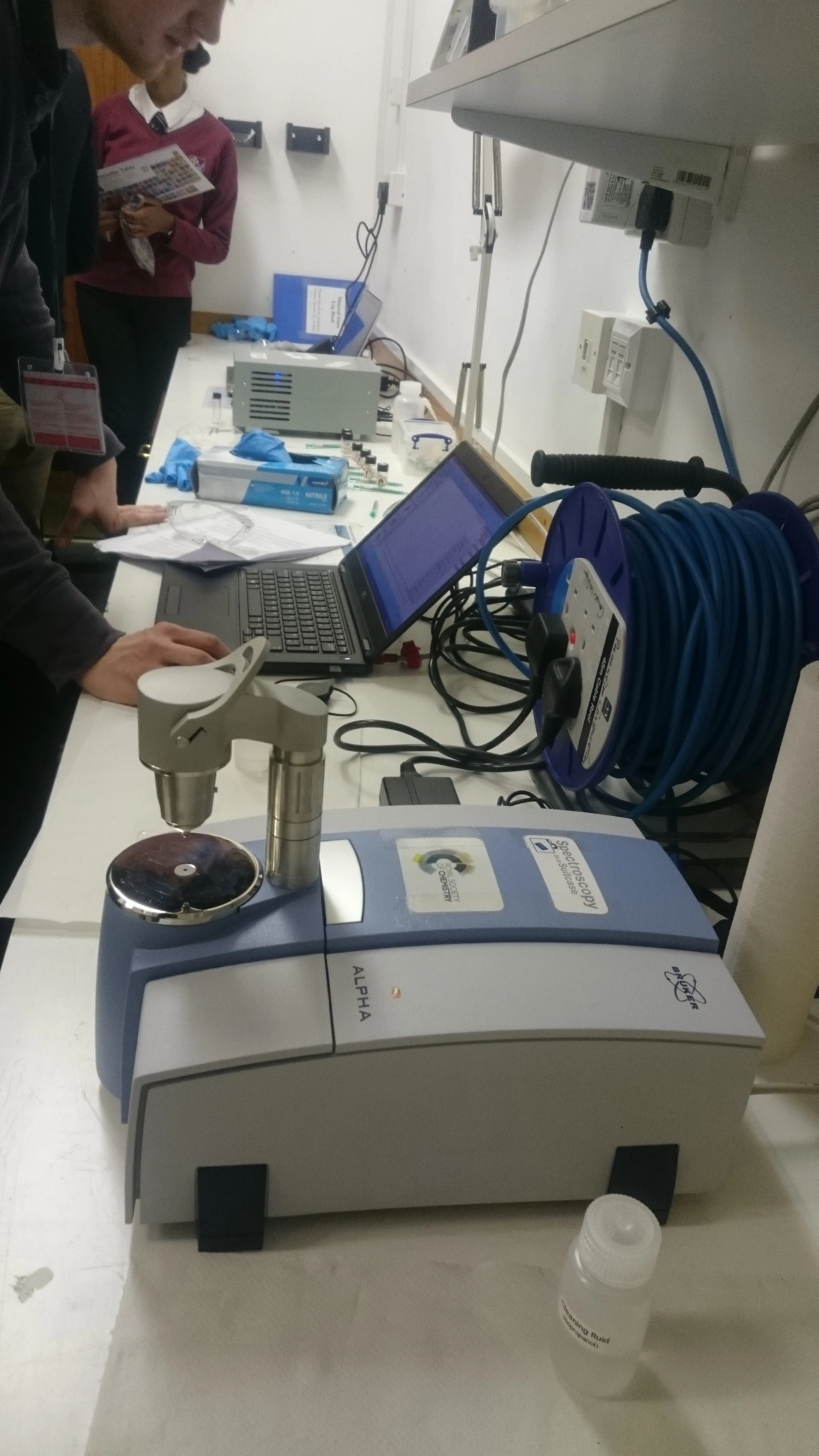

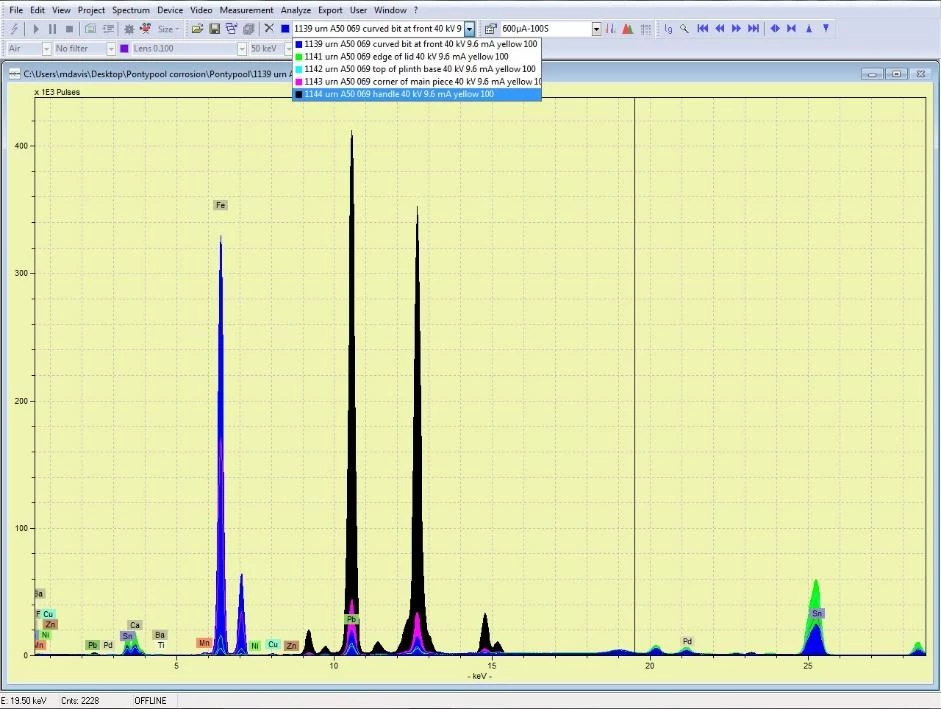

The students learned about Wales’s largest and most important mineral collection, the challenges of caring for it, and some of the analytical tools that help us: X-Ray diffraction (XRD), gas detection tubes, infrared spectroscopy (IR) and Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR). The XRD is part of the National Museum's own analytical facilities, operated by Tom Cotterell and Amanda Valentine-Baars in the Mineralogy/Petrology section. The other two technologies are covered by the curriculum and the students enjoyed the opportunity to prepare real samples, analyse them and interpret the results. To them, this made the subject a lot more real than just learning about them from books. It was also important that the analyses were undertaken not simply as a method per se, but in the context of answering genuine research questions at the museum.

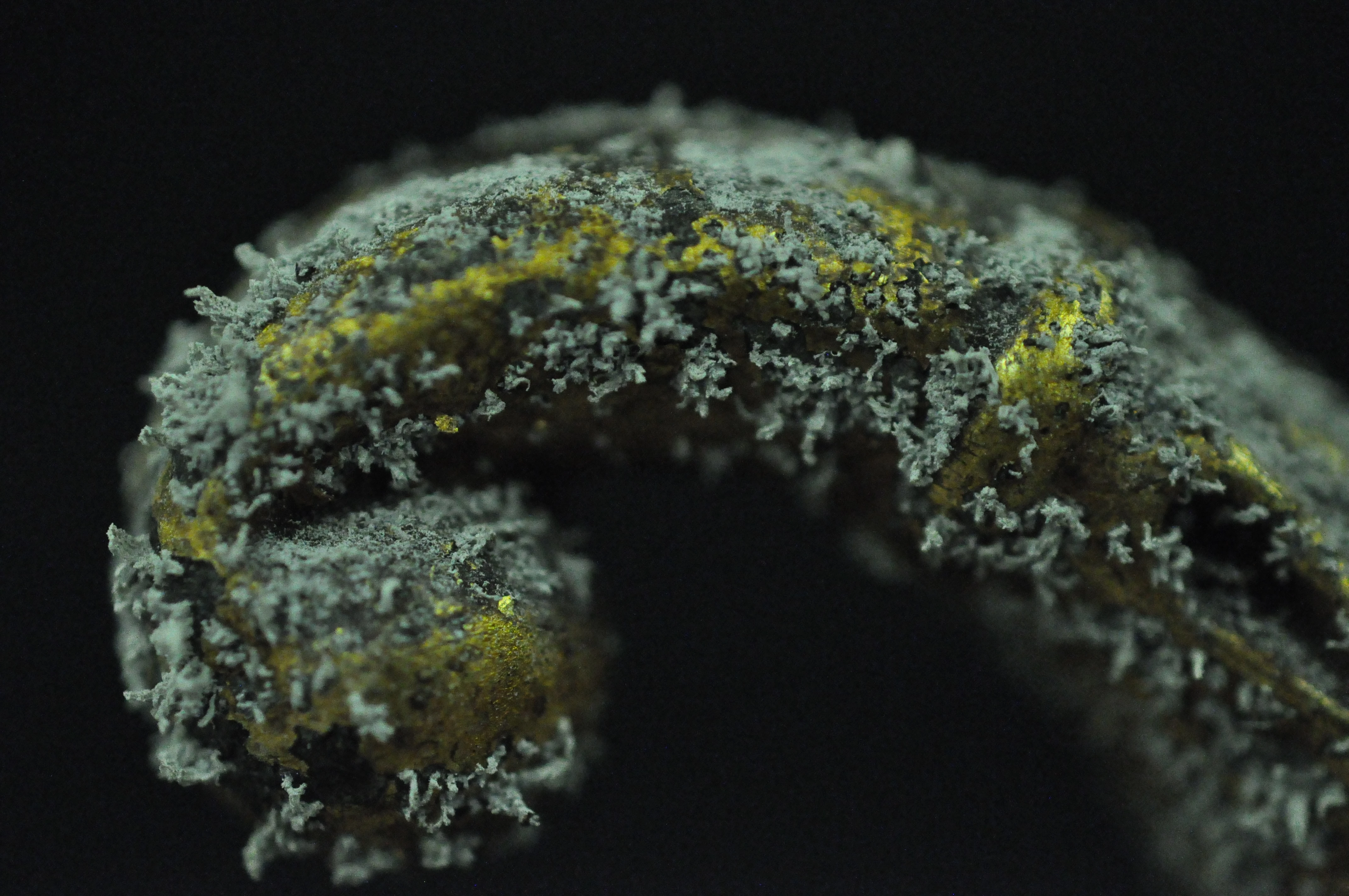

What does chemistry have to do with the care of collections? We undertake our own research on objects and specimens in the collections, and we collaborate with researchers at universities. In addition, the act of preserving our common heritage often throws up problems, as objects degrade and conservators need to work out why, and how to stop the degradation.

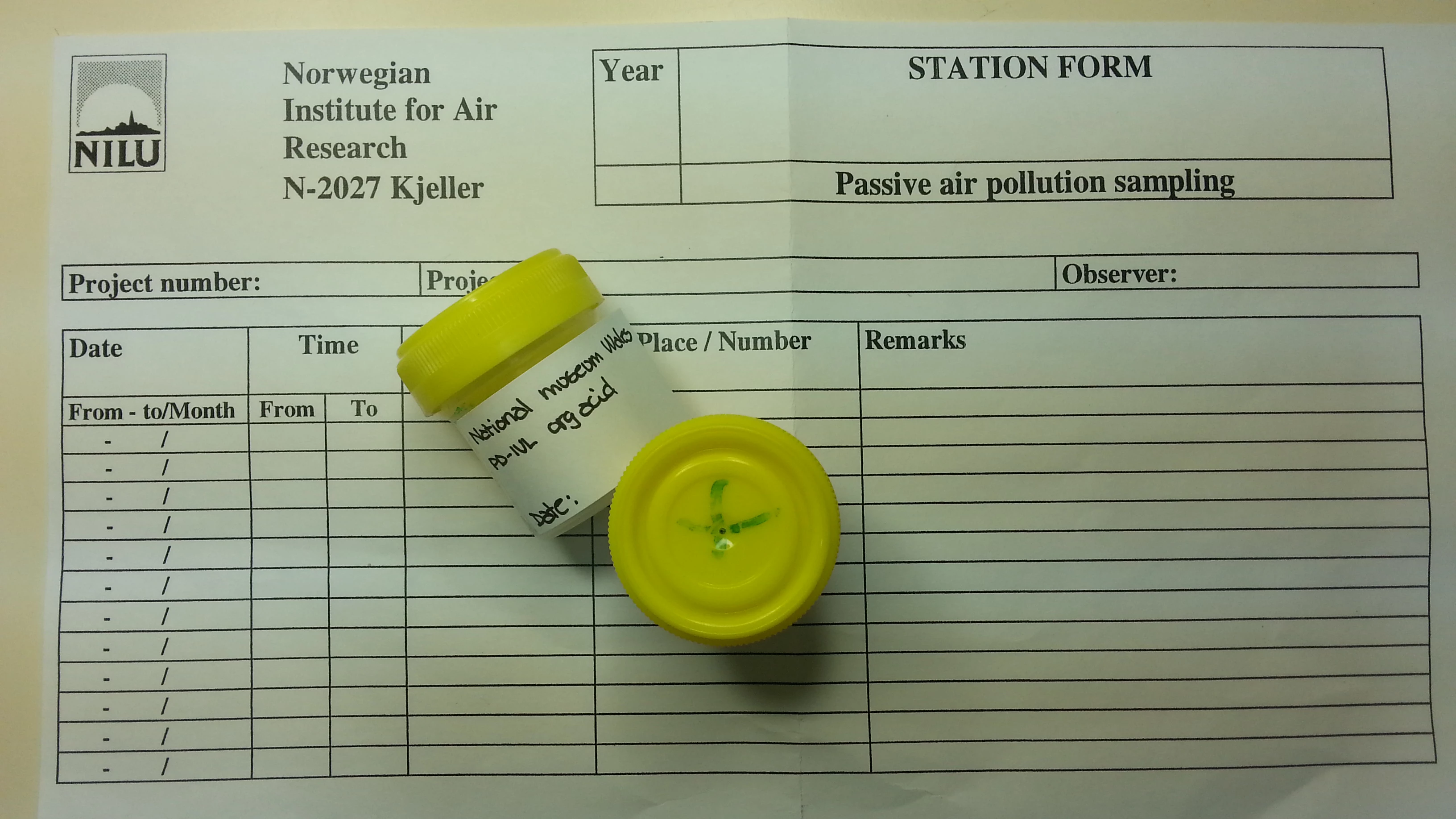

Often we cannot do this on our own, in which case we work with partners to investigate, for example, the corrosivity potential of indoor pollutants and their effect on mineral specimens in storage at National Museum Cardiff. These partners include Cardiff University’s Schools of Chemistry, Engineering and History, Archaeology and Religion (Conservation Department).

One of these collaborations sparked yesterday’s schools engagement project, run in conjunction with the museum's Conservation and Natural Sciences departments and kindly supported and funded by the Royal Society of Chemistry (South East Wales Section). The Royal Society of Chemistry provided an entire bench full of portable analytical equipment for the day, which the society's Education Coordinator, Liam Thomas, set up in the Mineral Store. Because of the interdisciplinary nature of the project, additional support came from Cardiff University’s School of Earth and Ocean Sciences.

Find out more about care of collections at Amgueddfa Cymru - National Museum Wales here.