All hail the dragon

, 7 July 2016

During the past two weeks our Geology galleries were closed for essential maintenance. Now they are open to the public again, much to the delight of anyone looking after dinosaur-mad 6-year olds, who, quite rightly, have been disappointed by the temporary withdrawal of some of National Museum Cardiff’s most popular displays.

So in you come for a peek of all those refreshed displays. But what’s that? Seemingly nothing has changed?? Everything still looks as it did before the ‘major refurbishment’ – so what was so major about it?

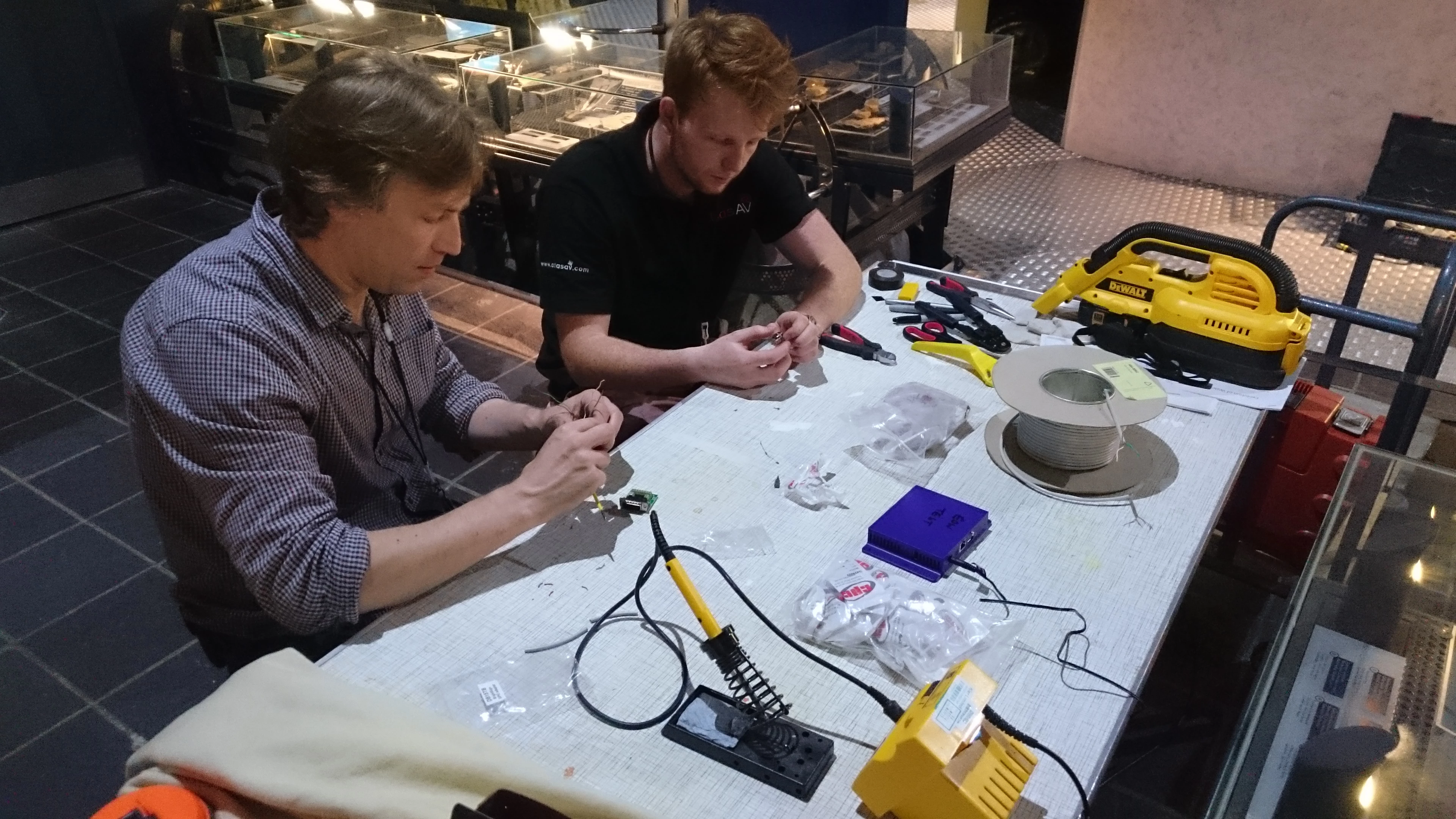

The idea of undertaking maintenance was not to change the displays – apparently our visitors are happy with the way they are – but to update technology and fix things that were broken. This is why you have to look closely to spot what we have been so busy doing. Very busy in fact; including the planning phase, which took several months, we had at least 23 people working on the gallery. It was very busy every day, with staff and contractors working around each other, from the dinosaur foot prints pavement all the way up to the ceiling (which is 12m high in this gallery).

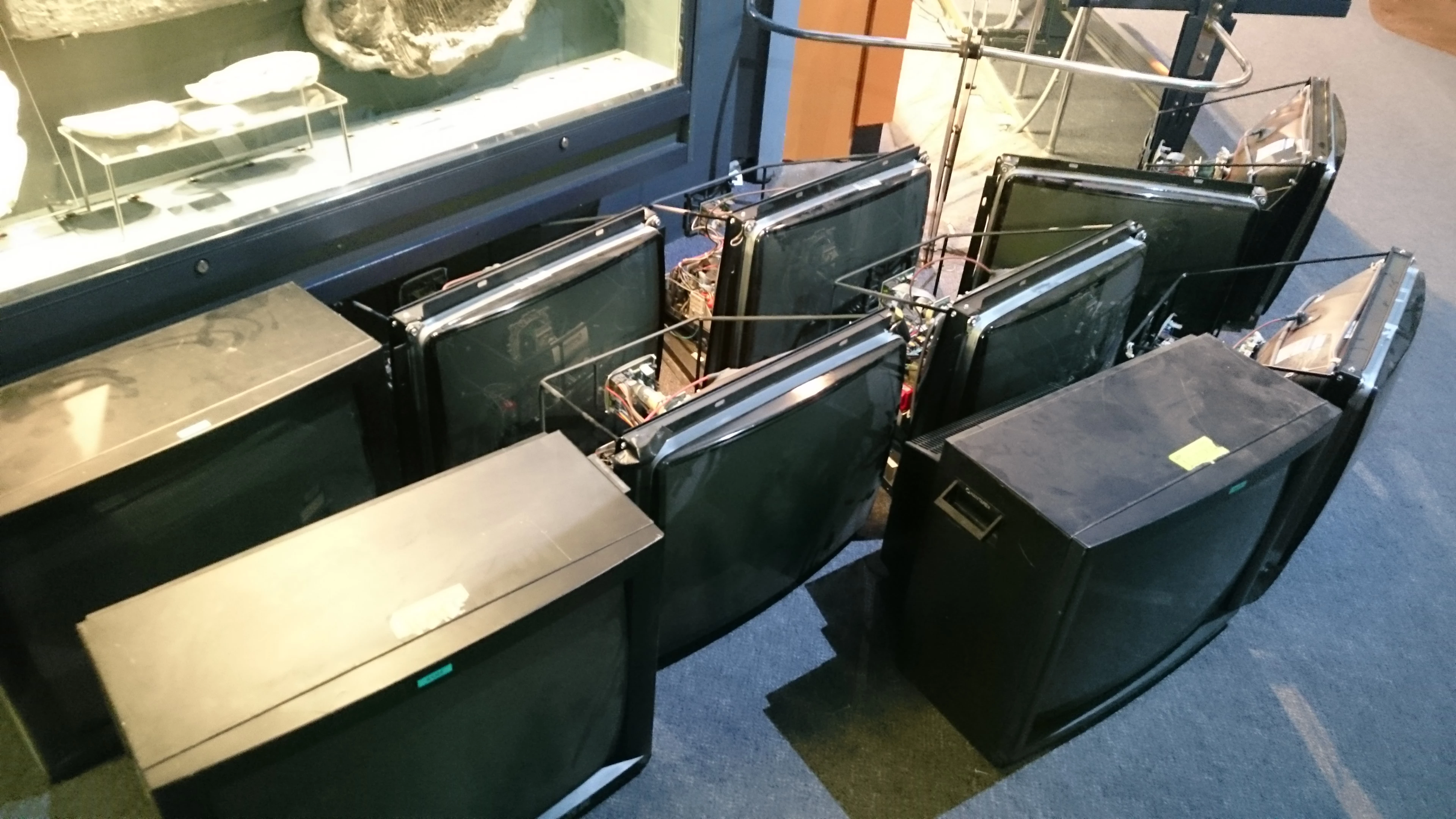

What you won’t notice is that the fire beams were replaced to alert us early and reliably in the event of a fire. You’ll have to look closely to spot the new lights: the spot lights underneath the ceiling are now all converted to LED. You may find that the image quality of the display screens is a million times better than it was before. What you certainly should notice is that the displays are much cleaner. We also repaired damage to displays. As the saying goes: if you touch - we need to touch up. The paint work, that is. And if anyone happens to walk into a display case the specimens inside move sometimes. If we don’t spot this early enough, they can topple off their shelf and break. We used the opportunity last week to put them all back in their place, hence our plea to you: this is now not a race to see how quickly they can be knocked off their perch again, so absolutely no prize for anyone who thinks they can dislodge the displays. Our specimens – which, actually, belong not to the museum but to the Welsh public – are fragile and repairing them costs tax payers’ money, which we do our best not to waste.

There is one thing that is entirely new to the gallery, something which will be obvious immediately to said 6-year old dinosaur enthusiast (and those of any other age, too): the new Welsh dinosaur now has a permanent home as part of our dinosaur display. A life-sized artist’s impression, feathers and colours and all, is now peeking from the early Jurassic back to its Triassic cousins. It is truly magnificent and inspiring, and actually one of the first models to represent the latest research that these kinds of dinosaurs were clad in feathers. The enthusiast in myself wants to add pathos to this announcement, which is difficult to express in a blog. Hence I’ll stop myself right here and simply invite you to come and see it.

Oh, one more thing. While working in the displays in the past two weeks we found countless sweet wrappers, discarded chewing gums and bits of sandwiches and apples in various hidden corners. These kinds of things encourage pests which we don’t want in the museum any more than you would want them in your house. We have the restaurant, café and schools sandwich room where you are welcome to eat, and there are bins in the Main Hall before you enter the galleries. We would be immensely grateful if you didn’t take any food into the galleries.

Find out more about care of collections at Amgueddfa Cymru - National Museum Wales here.