"Clapio Wyau" (Egg Clapping)

, 31 March 2020

Wooden Objects

We’re sure that you can think of many images surrounding us at the moment, in shops and in the media, associated with the Easter holiday: colourful chocolate eggs, fluffy chicks and rabbits, white lillies and simnel cakes to name but a few.

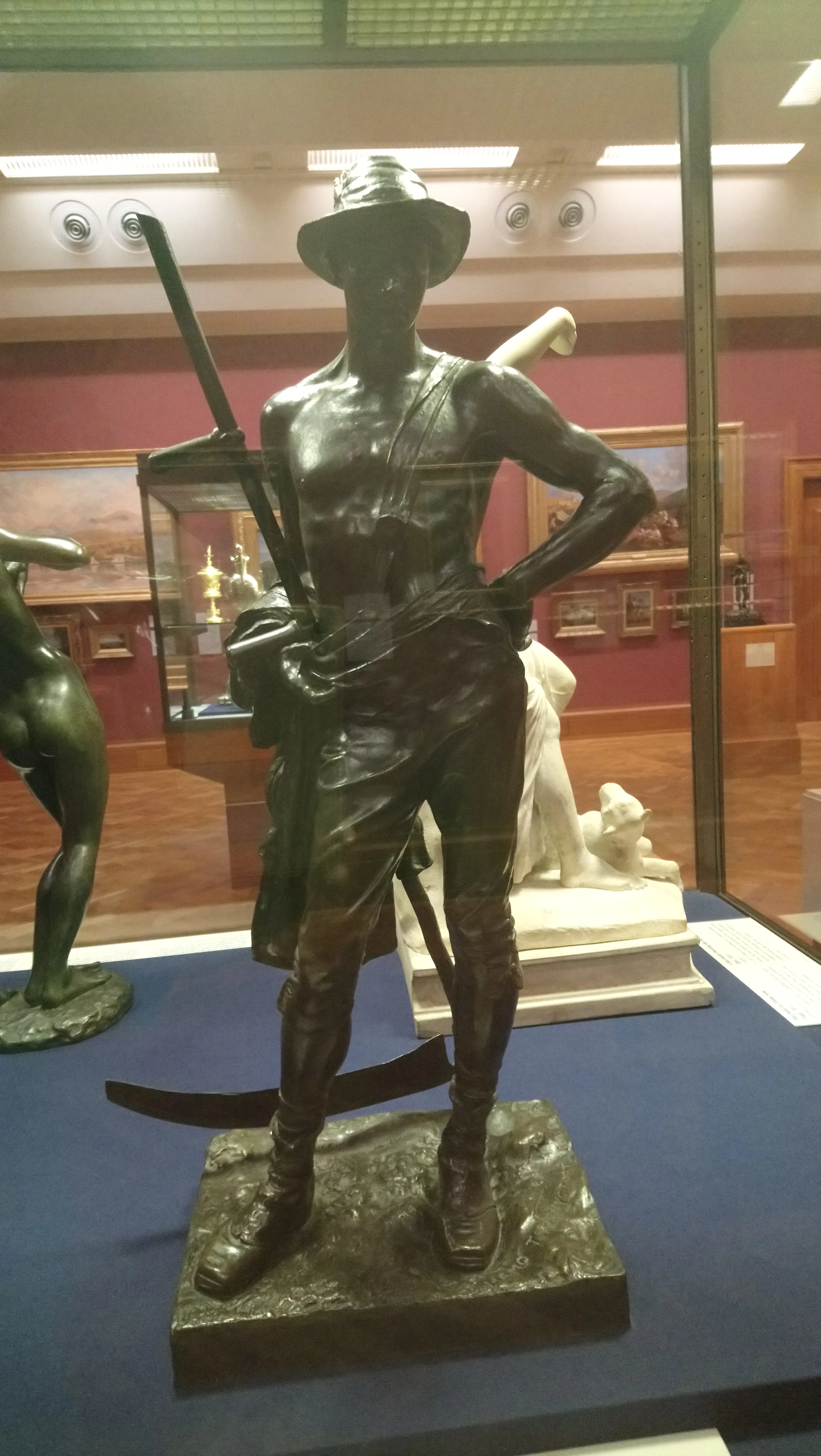

But can you guess what the two wooden objects in the images on the right are?

Easter Customs

This week I have been listening to recordings in the Sound Archive relating to Easter Customs. We have oral testimony on a wide variety of traditions: holding “eisteddfods”; “creu gwely Crist” (creating Christ’s bed); singing Easter carols; cutting hair and trimming the beard on Maundy Thursday in order to look tidy for the Easter weekend; eating fish, “hongian bwnen” and walking to church barefooted on Good Friday; drinking water from a well with brown sugar on the Saturday before Easter; climbing a mountain to see the sun “dancing” at daybreak and wearing new clothes on Easter Sunday; playing “cnapan” (a game of Welsh hurling using a ball of hard wood) on the Sunday following Easter.

“Clapio Wyau” (“Egg Clapping”)

But the custom that really caught my attention was the practice of going “egg clapping” on Anglesey. Going egg clapping before Easter was an extremely popular tradition among children years ago and the images on the right show the wooden egg clappers that the children would carry with them.

According to Elen Parry who was born in Gaerwen in 1895 and recorded by the Museum in 1965:

We would usually have an hour or two off school, maybe a day or two before the school would close so that we could go clapping before Easter. You would nearly be doing it throughout the week, but there was one special day when the school would let you go clapping for an hour or two. Nearly everybody would go clapping. You’re father would have made you what we would call a ”clapper”. And what was that? A piece of wood with two more pieces either side so that it would “clap”, and that’s what a “clapper” was.

The children would travel around local farms (or any homestead that kept chickens). They would knock on the door, shake their clappers and recite a short rhyme similar to this one:

Clap, clap, os gwelwch chi’n dda ga’i wŷ

Clap, clap, please may I have an egg

Geneth fychan (neu fachgen bychan) ar y plwy’

Young girl (or young boy) on the parish

And here’s another version of the rhyme from Huw D. Jones, Gaerwen:

Clep, Clep dau wŷ

Clap, Clap, two eggs

Bachgen bach ar y plwy’

Young boy on the parish

The door would be opened and the occupier would ask “And who do you belong to?” After the children had answered, they would each receive an egg. According to Elen Parry:

You would either have a small pitcher, a small can, or a basket with straw or grass on the bottom. And then everybody would get an egg. Well, by the time you’d finished, you might have a basket full of eggs.

The inhabitants of the home would usually recognise the children and if a brother or sister was missing, they would place an extra egg in the basket for siblings. Mary Davies, from Bodorgan, born in 1894 and recorded by the Museum in 1974 recalls:

And if the family in the house knew these small children, knew their siblings, and some were missing, they would also give them an egg for those brothers or sisters.

Eggs on the Dresser

Having returned home, the children would give their mother the eggs and she would place them on the dresser. The eldest child’s egg would be placed on the top shelf, the second eldest’s egg on the second shelf and so on.

With plenty of energy and determination, an impressive haul of eggs could be had. Joseph Hughes, born in Beaumaris in 1880 and recorded by the Museum in 1959 remembers:

Some would be quite brazen-faced and would have been clapping solidly throughout the week. They would have a hundred and twenty eggs. I remember asking my wife’s brother, “Did you go clapping, Wil?”, “Well, yes”, he said. “How well did you do?”, “Oh, I only got a hundred and fifty”.

A Type of Begging?

Even though most people would give the children eggs, some would refuse and answer the door with a disgruntled “Mae’r ieir yn gori” (“The hens are brooding”) or “Dydy’r gath ddim wedi dodwy eto” (“The cat hasn’t laid eggs yet”). Some parents would also be wary of allowing their children to go clapping, considering it to be a type of begging. This is what one interviewee had to say:

My father would never be happy for us to go because everybody knew who my father was. Well, my father never liked the fact that we had been begging at doors, but we would still go

Revival

It’s great to see that the tradtion of clapping is now enjoying a revival on Anglesey. It seems, for one week only, it’s still safe and acceptable in Wales to put all your eggs in one basket.