Amy Wyatt is a Professional Training Year Intern from Cardiff University, find out more about Amy's project this year

A herbarium is a collection of preserved plant specimens that have been stored appropriately, databased and arranged systematically to ensure quick access to students, researchers and the general public for scientific research and education. The Welsh National Herbarium contains vascular plants, bryophytes (mosses and liverworts), lichens, fungi, and algae. In the vascular herbarium, specimens are arranged by plant family/genus, and stored alphabetically. Specimens are stored in tall cabinets within the herbarium which is kept cool at all times. Each cabinet usually contains one taxonomic group of plants, for example members of the genus ‘Rubus’ have their own cabinet/section within the herbarium. And within the ‘Rubus’ cabinet, you will find individual species of Rubus (Rubus occidentalis-black raspberry, Rubus aboriginum–garden dewberry), each with its own folder containing all specimens of that species. Some specimens have been digitised and placed on an electronic system to make accessing records and ‘borrowing’ specimens to other institutions easier.

Herbaria are essentially the ‘home’ of historical plant records, containing information that would otherwise be lost in time. It is the curator’s role to ensure that all specimens are kept contamination free, are stored according to the correct guidelines, and are all stored systematically. The herbarium is checked regularly for infestations, and strict guidelines are put in place to ensure all specimens remain in pristine condition. Any loss or damage to specimens would be catastrophic because of the irreplaceable nature of collections. Herbaria also contain type specimens, individual specimens that an author based their description on when describing a new species. So, damage to these specimens has wide devastating impacts to not just museum collections, but science and taxonomy as a whole.

Who benefits from herbaria?

HISTORIANS: Specimens stored in the herbarium can give insights into the daily life of people in history. Collections like the economic botanic collection contain plants and botanical items that were of important domestic, medicinal, cultural use to society in the past. This collection contains herbs, dyes, textiles and culturally important items that are kept demonstrate their importance to world culture through displays, museum visits and exhibitions! Historians can also use herbarium collections for project collaborations, for record of discoveries and for exploration.

BOTANISTS: The most obvious field that benefit from herbaria is botany; botanists are scientists that exclusively study and perform experiments on plants. Some herbaria records span back hundreds of years, so this gives botanist a unique chance to look at how plant life has changed in this period of time. There are many studies that can be performed on herbaria entries, and usually depends on the specialist skills of the researcher looking at them. Botanists can look at changes in stomatal density, how a plant species has changed over time, when invasive species were first documented in the herbarium, what plant species are abundant at a particular period of time, flowering times of plants, if there are any gaps in plant records, amongst a whole host of other information

SCIENTISTS: It’s not exclusively botanists that benefit from herbaria, other branches of science can also use the collections in their research. Biologists, conservationists and ecologists can benefit from the specimens found in herbarium and frequently use collections for ongoing research. Specimens provide a detailed account of plant life, and this information can be used to look at diversity and abundance of certain plant species, patterns of plant distribution, record of rare plant sightings (e.g. here we have a very precious collection of ghost orchids, which were thought to be extinct until 2009 and have only been sighted a hand full of times since), environmental responses to changes in the climate or weather, to educate students, etc. Herbaria can also be an excellent source of collaboration between universitys and the Museum, providing networking potentials.

TEACHERS/PEOPLE IN EDUCATION: Herbaria and museums are a great source of outreach for education of the public. Collections like the economic botany collection provide historical context to important botanical items (e.g Indigo, cinnamon) that have part of our culture behind them. The herbarium also has active researchers working upon vascular plants, lower plants, and diatoms. This work is often used to educate the public at events like museum exhibits, guided tours of the herbarium, conferences, and shows like the RHS flower show.

What can be found in herbaria?

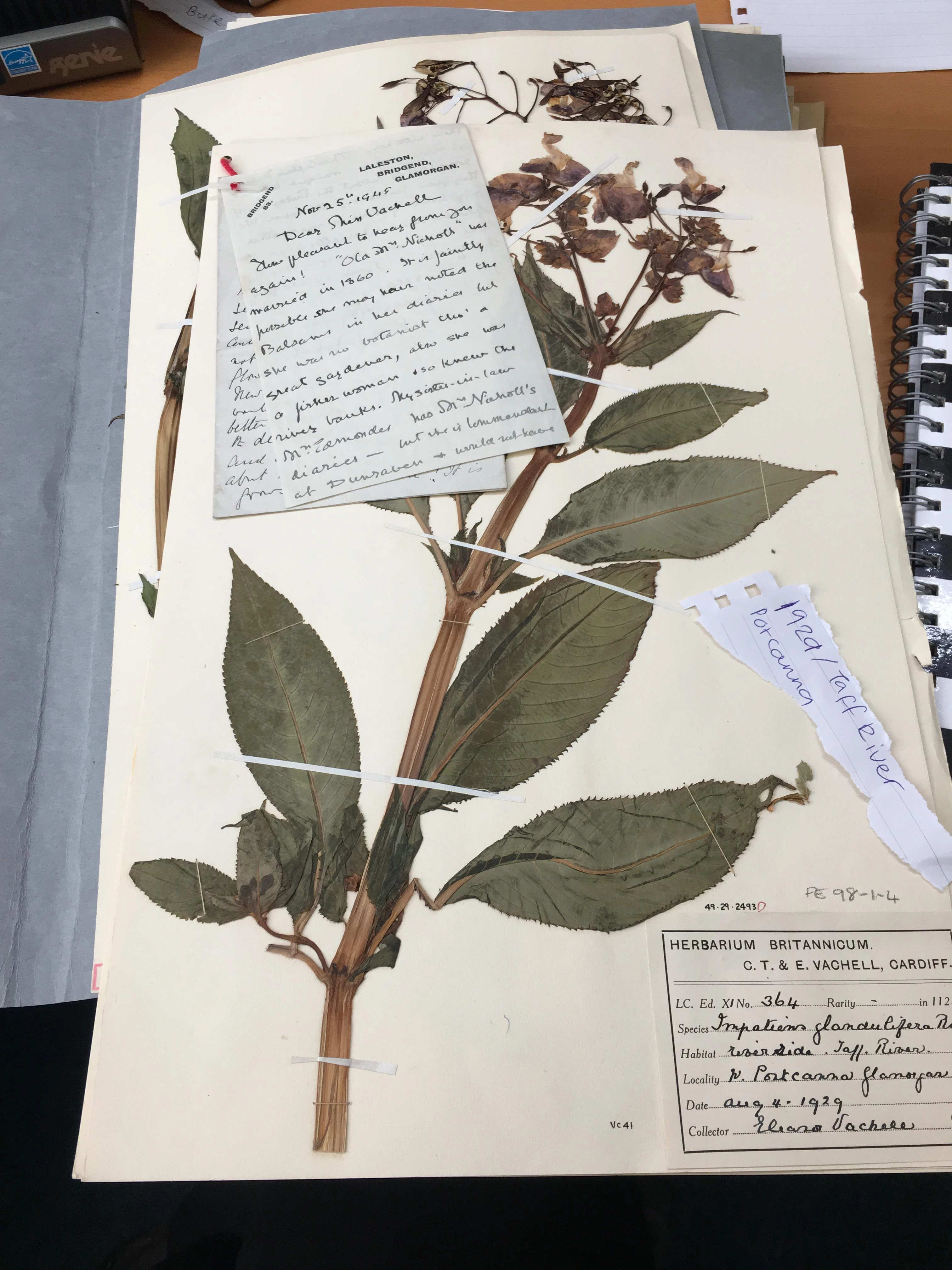

Vascular plants - Vascular plants are essentially ‘higher plants’ and are composed of all individuals that have water conducting tissue in their ‘stems’; flowers, grasses, trees, ferns, herbs, succulents, etc. are all types of vascular plants. These types of plants are usually stored on archival herbarium sheets, but the method of preparation and storage may depend on the contents of the specimen. Plants that are easily pressed are mounted onto acid free herbaria sheets, with a descriptive label for each specimen. These herbaria specimens must contain reproductive and vegetative organs, which are critical for species identification in plants. Any plant parts that can’t be easily pressed, e.g. tubers, bulbs, fleshy stems, large flowers, cones, fruits, etc are usually dried and placed in boxes or paper bags that are associated with other parts of the specimen.

Bryophytes (mosses and liverworts) - Bryophytes include both liverworts and mosses are generally described as ‘lower plants’ and represent some of the oldest organisms on earth. Both groups grow closely packed together in matts on rocks, soil or trees. These types of plant don’t have regular water conducting tissue, so rely heavily on their environment to regulate their water levels. Both mosses and liverworts are unsuitable for ‘pressing’ as key features used in identification would be damaged during the process. Instead, specimens are dried, decontaminated and placed in packets, boxes or paper bags to ensure their long-term storage.

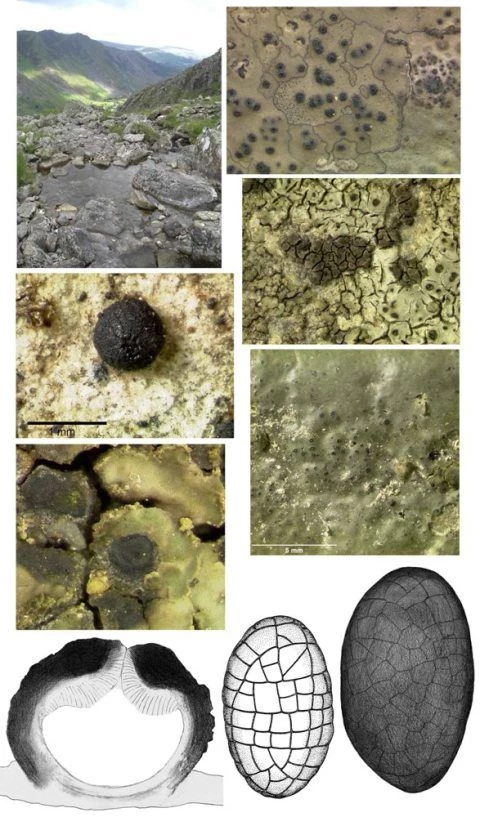

Lichens - Lichens are unique in plant taxonomy because they are an organism composed of two separate organisms in a symbiotic relationship. A lichen is composed of a fungus, and either an algal cell or bacterial cell. The fungal portion of the organism extracts organic carbohydrates and nutrients from the environment, and the algal/bacterial portion of the organism undergoes photosynthesis to capture energy from the sun. Because lichen are difficult to extract from their environment, commonly they are collected still attached to their substrate (rocks, bark, soil crusts) and stored in boxes.

Fungi - fungi are filamentous, simple organisms that occupy almost every habitat on earth. Fungi are not plants and belong in their own kingdom, as they contain no chlorophyll and extract organic nutrients directly from their environment. Surprisingly, most fungi are totally microscopic and invisible to the naked eye dwelling deep in the ground connected by a network of hyphae. It is only a small portion of macroscopic fungi that produce fruiting bodies we know as ‘mushrooms’. Fungal bodies cannot be pressed, they must instead by dried thoroughly and stored in cases or boxes.

Algae - Algae are a very diverse group of non-flowering aquatic organisms that contain chlorophyll, so can photosynthesise to produce energy for themselves. Algae are very important to the earth, and it’s estimated that they produce 70-80% of the earths atmospheric oxygen. The term ‘algae’ covers wide range of organism including sea weed, kelp, ‘pond scum’, algal blooms in lakes or pools, diatoms, etc. These groups are not necessarily closely related and can exist in a huge range of different forms! Collecting and preserving algae can be done in two ways, storing them in liquid to preserve the specimen or dry preserving the specimen on herbarium paper or a microscope slide. What method is best usually depends on the species being collected and its properties.