Tokens of Love

, 23 January 2024

Carved cow’s horn, 1758

Today in Wales we celebrate Santes Dwynwen, the patron saint of friendship and love.

With Valentine’s Day also on the horizon, what better time than now to explore some of the objects in our collection which were given as tokens and symbols of love. Most of us are familiar with the concept of love spoons and their significance to Wales, and you can learn more about their history and designs here.

But in this blog, I would like to focus on some of the lesser-known objects related to love in the collection, starting with the Knitting Sheath.

Knitting needle sheaths were often carved as love tokens. Sheaths were worn by knitters to hold one of their needles while they worked. This allowed them to use their free hand to manipulate the yarn. The sheath was either tucked into the knitter’s waistband or tied around their waist.

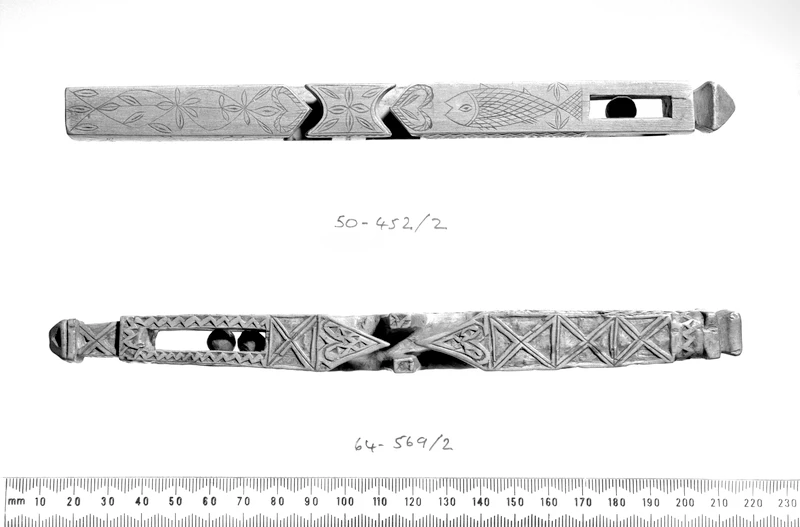

This knitting sheath is inscribed with the date 1802, with the name ‘Thomas Smith’. It was probably made as a present and love token, like several others in our collection. It is decorated with a flower, heart, and fish motif.

Top: Carved knitting needle sheath, 1802 Bottom: Carved knitting needle sheath, 1754

The example below it is of an earlier date and was made in 1754.

Like many of the lovespoons in the collection at St Fagans, both sheaths feature balls carved within a cage – this was commonly thought to represent the number of children desired by the carver.

Another popular love token was the Staybusk. This was a piece of wood which was inserted into the front of a woman’s stays to keep the torso upright. They were usually made from whalebone, wood or bone. A busk was often given to a woman as a love token from a suitor because they were positioned close to the heart. Many were carved or painted with inscriptions and motifs, such as hearts, initials and flowers.

Below is a carved wooden staybusk from Llanwrtyd, Powys. It is inscribed with the initials RM and IM.

Carved wooden staybusk from Llanwrtyd

The symbol of the wheel features heavily on this staybust, and it was said that this represented a vow by the carver to work hard, and to guide a loved one through life.

Tokens such as knitting sheaths, staybusts and lovespoons were available to people of all classes. Made with affordable materials that were readily available, each token was completely unique and driven by the emotion and passion of the carver.

Carved love tokens encompassed a wide variety of styles and designs, and came in all shapes and sizes, such as this cow horn, beautifully carved in 1758 in the Aberystwyth area, as a gift by Edward Davis for his sweetheart Mary.

Carved cow’s horn, 1758

These tokens shed a unique light on the emotional experiences of the receiver, and those who loved them. They were cherished objects belonging to ordinary people, whose stories are so often hidden from history. Through the beautifully carved symbols and motifs on the love tokens, we can learn a little about their hopes and desires and gain a glimpse into their very own love stories.