Guest Blog: 'The Welsh at Mametz Wood'

, 8 March 2016

While I enjoy going to the Youth Forum very much, I have to say a once-in-a-lifetime experience was not what I was expecting when I turned up last week. But there we were, in the art conservation room, a few feet away from an original Van Gogh, out of its frame on the next table, having just come back from being loaned to an American museum. I could have actually touched it (and I was quite tempted, though of course I didn’t).

Now, I’m not exactly an art aficionado, as you can properly tell by the way I haven’t included the name of the painting because I don’t know it, but I have to say it was pretty amazing.

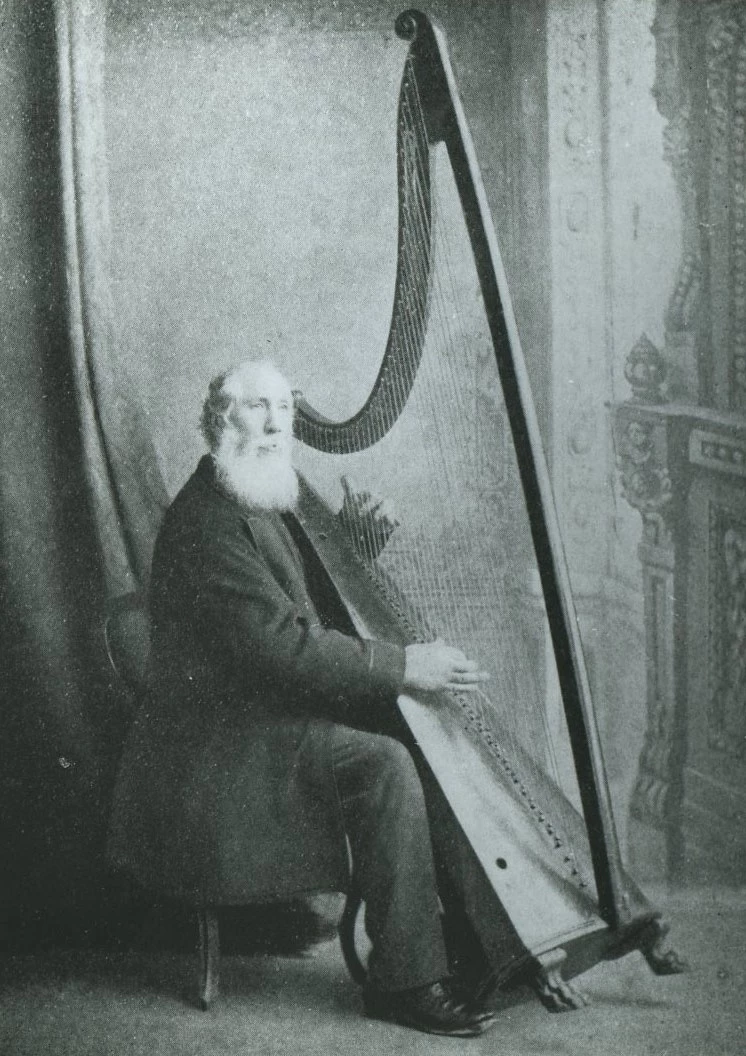

However, the focus of the meeting was actually the imposing The Welsh at Mametz Wood by war artist Christopher Williams, which is going to be part of a new exhibition focusing on the First World War battle at Mametz in a few months time.

This is a battle where hundreds of men from the Welsh Division were killed in July 1916, and thousands more were injured, something that the painting certainly doesn’t shy away from. It’s big, bloody, and quite brutal. While war sketches of poppies blooming among the trenches and beleaguered soldiers limping through mud evoke the tragedy of the slaughter that took place, they arguably don’t capture the fighting itself, but the aftermath, the few moments of calm in a four-year storm.

Christopher Williams (1873-1934), The Welsh Division at Mametz Wood, 1916 © National Museum of Wales

Williams’ painting does the opposite. The desperate struggle of the hand-to-hand slaughter was immediately obvious. It felt almost claustrophobic, the way the soldiers were almost piling on top of each other, climbing over their fallen comrades to try and take out the machine gunner. It was certainly a world away, as we discussed, from the posters bearing Lord Kitchener encouraging young men to enlist. We also talked about the way the painting is quite beautifully composed, almost in a Renaissance style.

It was hard to look at, but at the same time it was something you wanted to look at.

After this, we went to the archives to look at some sketches made by Williams and other artists while at the trenches. I was about to get goosebumps for the second time that evening - one of them still had mud from the trenches staining the edges!

In any other context, 100-year-old mud probably wouldn’t have been very exciting, but this mud is so strongly linked in people’s minds with images of the First World War.

Think of the trenches, and you think of mud. People slept, ate and died surrounded by this mud; it seems to be inextricably bound up with the nightmare of having to live and fight in that environment, and made looking at the sketches even more powerful.

Another document we looked at was a sort of manual given to recruits of the Royal Welsh Division, containing poems, stories and pictures that the soldiers would have submitted themselves. It was touching to see one of the ways they would have injected moments of humour into their lives as soldiers, and also their own perspectives on their experiences. All in all, I’m really looking forward to seeing how this exhibition comes together, and learning more about Mametz, a part of the war I hadn’t even heard of until a couple of weeks ago.

Holly Morgan Davies,

National Museum Cardiff Youth Forum