Digitising botanical specimens from South Asia for the Rights and Rites project

, 21 February 2023

Over the last 7 months curators have been working on an Arts and Humanities Research Council (AHRC) funded project, Rights and Rites. The project aims to work with members of the local community to reinterpret Botany specimens from South Asia, primarily in the Economic Botany Collection, to provide cultural context, to understand traditional methods of using the plant products and to improve access to the collections.

The Economic Botany Collection, comprising approximately 5500 specimens, contains a variety of different plant products, such as leaves, roots, fibres and seeds, all with significant economic, cultural or medicinal value. In addition, the project has drawn on collections of herbarium specimens, botanical illustrations, lower plant specimens and materia medica.

A key approach to making the collections more accessible is to digitise the specimens, producing images that can be shared with museum staff, researchers and communities outside of the museum. Several techniques have been used to digitise the specimens, depending on the size and form of the specimens.

Working with different equipment and technology, Research Assistant Nathan Kitto has built up a collection of over a thousand images that include vascular herbarium sheets, specimens in jars and boxes and beautiful hand drawn illustrations. These images will be stored on the museum’s Natural Sciences online image library, along with specimen data, which can then be used as a research and reference tool. In future the images will be made more widely available through Collections Online

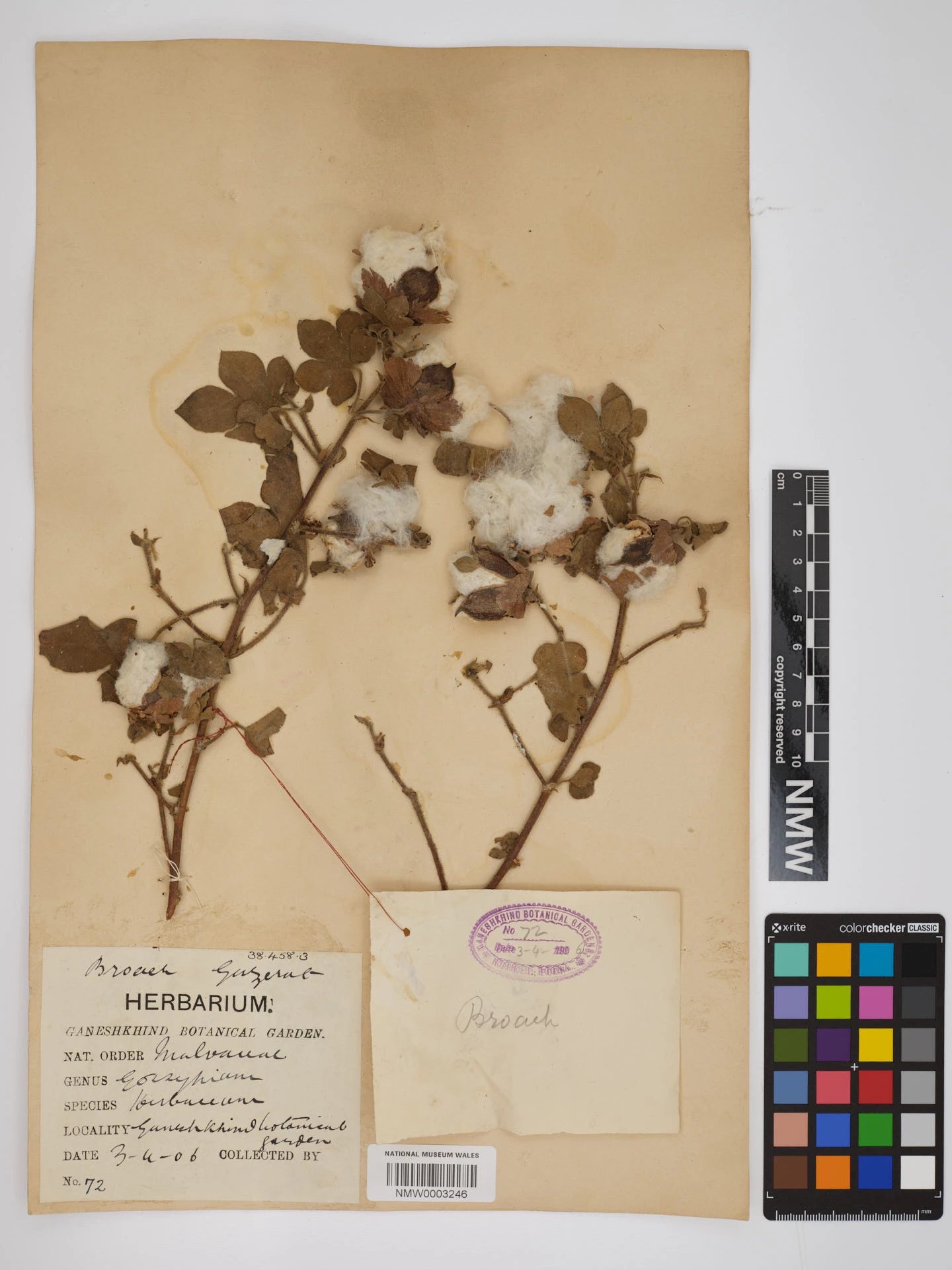

Initially 2D images were created using a high quality digital SLR camera. This is a vital step to record unique details of the specimen, including accession number, common name and scientific species name and origin. A colour chart is normally included in the image to ensure consistency in colour, size and scale. Micrograph equipment also has been used to take extreme close ups of specimens. By magnifying the specimen, it is possible to distinguish fine details which cannot normally be seen, giving a completely different dimension.

New high-tech 3D scanning equipment has been purchased recently, supported by a grant from AHRC. Very detailed 3D scans have been produced of selected specimens that were suitable in terms of size and shape. The equipment allows us to capture a full 3D image of a specimen and permits end-users to rotate the specimen so that it can be viewed from any angle, providing quite a different perspective compared to a two-dimensional image.

The scanners work by taking multiple frames or images of the object from different angles to build up a real 3D image. One type of scanner, the Artec Micro, has a more automated process; with the equipment doing most of the work, by rotating and choosing specific angles from which to take high quality images. In contrast, the Artec Space Spider is a handheld scanner, controlled by the operator, that takes a higher number of images while the object is rotating. It was very easy to use and was very accurate as well. After acquiring enough images from different orientations, the images are then merged using specialised Artec Studio software. With a few tweaks and repositioning, a 3D model is created and uploaded to Sketchfab. This is the online studio where the 3D image of the specimen can be optimised with lighting and positional edits. The Economic Botany 3D image library, which can be found here, displays 21 models of specimens, supplemented by information on traditional medicinal and cultural uses of individual species.

There are many benefits of creating 3D models of museum specimens; they make the collection accessible to anyone, and suitable for online searches. Preservation of the object is facilitated, since it allows the user to get a close look at delicate objects without the danger of causing damage. A digital asset will not deteriorate with time and can be copied and stored in multiple places and it also can be used to create 3D printed models. Furthermore, a digital 3D object allows for a different interaction with an object.

The 3D models have been used to make museum specimens accessible to members of the public during community workshops. This form of engagement generated very positive feedback and provided a good starting point for discussions about museum collections and the many uses of the specimens. The creation of these 3D models is just the starting point. The curators on the Rights and Rites project look forward to seeing how people will continue to interact with the models in the future and hope it can be a useful and engaging resource for the public and museum to share. If you have any comments about the objects shown in this blog, then please contact: Heather.Pardoe@museumwales.ac.uk.