A Window into the Industry Collections - September 2015

, 29 September 2015

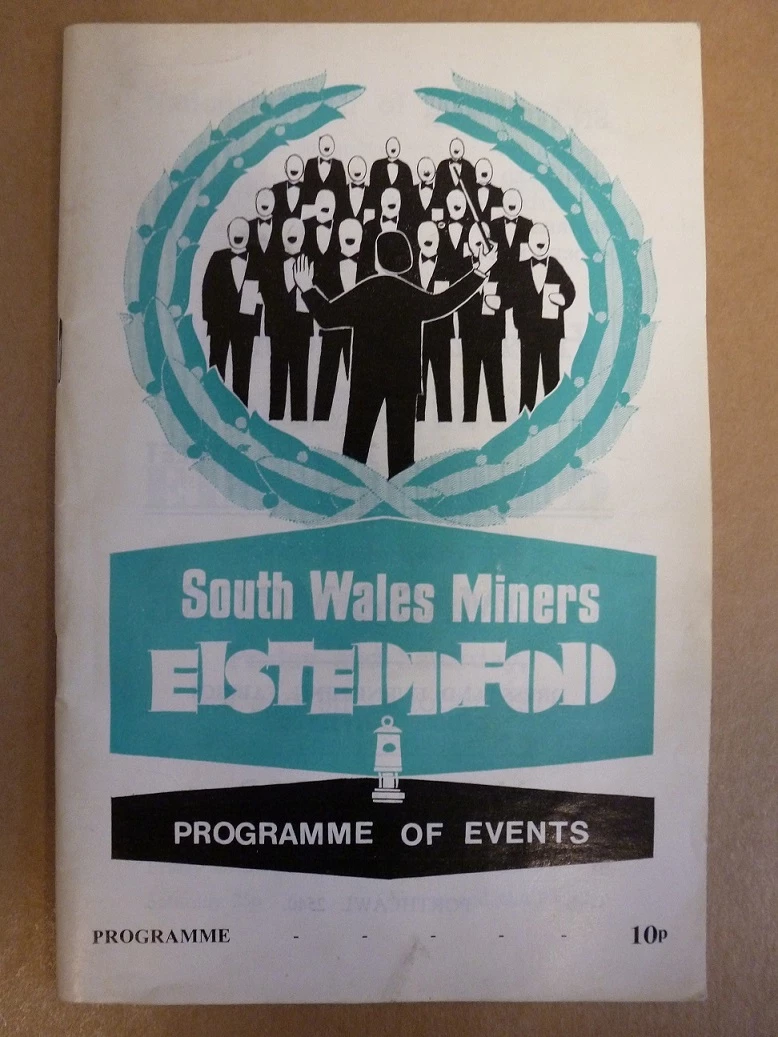

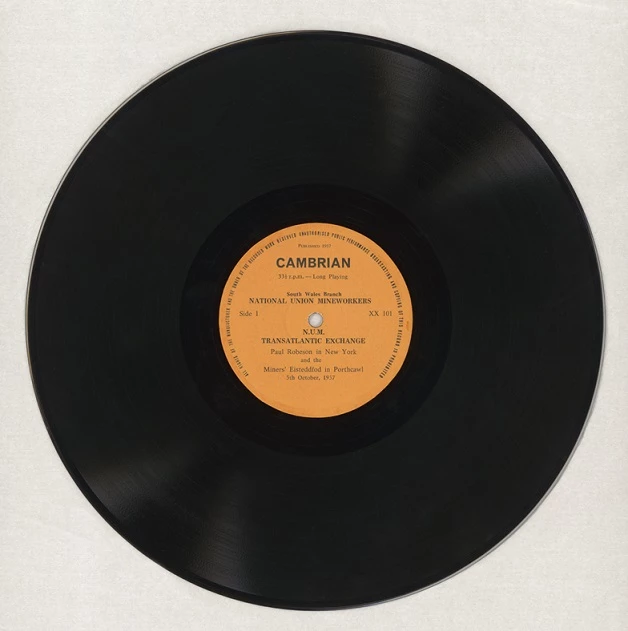

The South Wales Miners’ Eisteddfod started in 1948 in Porthcawl, and Amgueddfa Cymru has a number of programmes for various years in the collection. This copy is for the Eisteddfod held in October 1971, and has been donated recently. The Porthcawl Eisteddfod was made world famous in 1957 when the famous US actor, singer and Civil Rights Movement leader, Paul Robeson made a famous broadcast. In 1938 Paul Robeson had been in Wales filming 'The Proud Valley'. This film introduced him to the miners of the Rhondda, and he was invited to sing at the South Wales Miners’ Eisteddfod. In 1950 Robeson had been denied a passport to travel abroad. Still wanting to appear at the Eisteddfod he used the transatlantic telephone cables to transmit his concert from New York to an audience of miners and their families in the Grand Pavilion at Porthcawl. It was a gesture of international solidarity. There is a copy of this recording made on 5th October 1957 in the museum's collection.

This pocket watch and protective snuff tin has been donated this month, and was used by the donor at Cwmtillery Colliery in the late 1970s. A protective case was a common way for mineworkers to protect their watches from dust and knocks. In this case a new use has been made for the snuff tin. We have other protective watch cases in the collection that were speciffically made for that purpose. The pocket watch shown is an example of a pocket watch in a protective brass and glass pocket watch case, which was known as a turnip. This watch was owned by Mr Evan Weston who was killed in the explosion at Universal Colliery, Senghenydd, 14 October 1913.

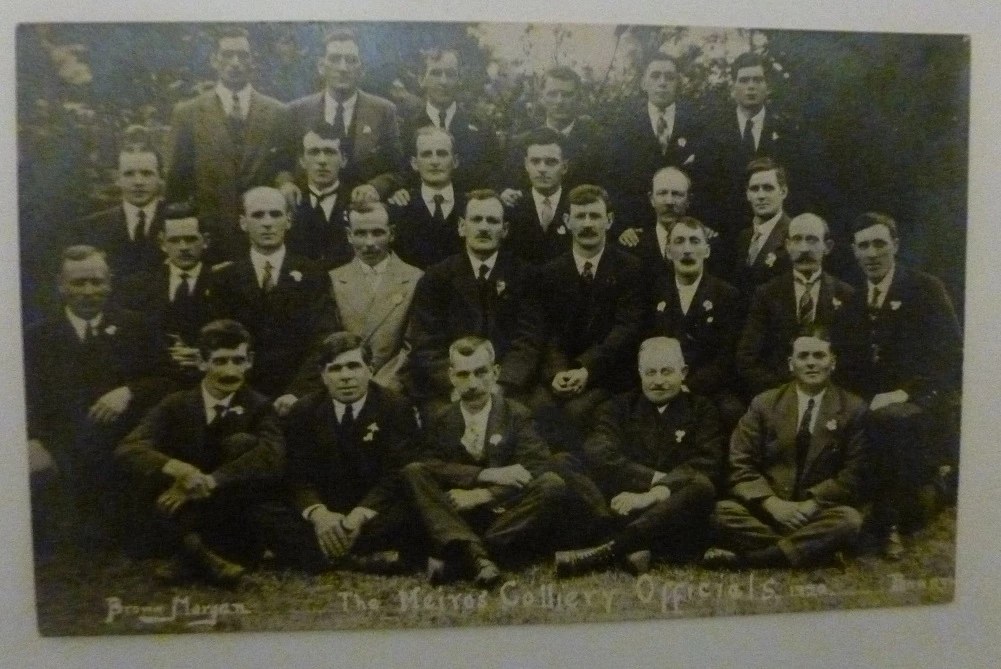

The final object this month is this real photograph postcard showing the officials of Meiros Colliery, Llanharran in 1920. Meiros Colliery probably opened in the 1880s, and closed about 1938.

Mark Etheridge

Curator: Industry & Transport

Follow us on Twitter - @IndustryACNMW