Often, people announce - with a knowing look in their eye – that Science knows more of the surface of the moon than it does of the deep oceans of our own planet. This platitude is probably vague enough to be considered accurate, but it ignores a salient fact about Earth: a lot more is happening here, especially in the oceans, and even the smallest sample of abyssal mud contains a wealth of life sufficient for years of study. Oceanographic missions are rare because each one produces a superabundance of data and specimens that require decades of work to describe and interpret. The simple problem of man-hours and scarcity of expertise in niche fields is what limits the scope of modern oceanography (and the funding available to it).

Blue-sky thinking

The index case for this problem was that of the Challenger expedition of 1872-76, a sprawling endeavor to “investigate the physical conditions of the deep sea in the great ocean basins” - scarcely has an expedition brief been bolder or more vague – with a navy vessel and a small group of gentleman-scientists headed by Charles Wyville Thomson. Wyville Thomson had headed earlier voyages to chart the waters around the British Isles, discovering life down to depths of 1200 metres; he had become the patriarch of the nascent discipline of oceanography, which – before Challenger – was limited to a hazy understanding that a lot of the oceans were very deep indeed. The vessel set out with a complement of around 250 men of all ranks and stations, weighing anchor in Portsmouth in December 1872 and zigzagging down the Atlantic coast of Europe before striking out towards the Caribbean. She would sail on for almost eighty thousand miles, crossing and re-crossing the Atlantic before swooping down to the sub Antarctic Kerguelen archipelago, circling Australia and the Pacific, and finally passing through the Straits of Magellan at the tip of South America on her way home.

A challenging legacy

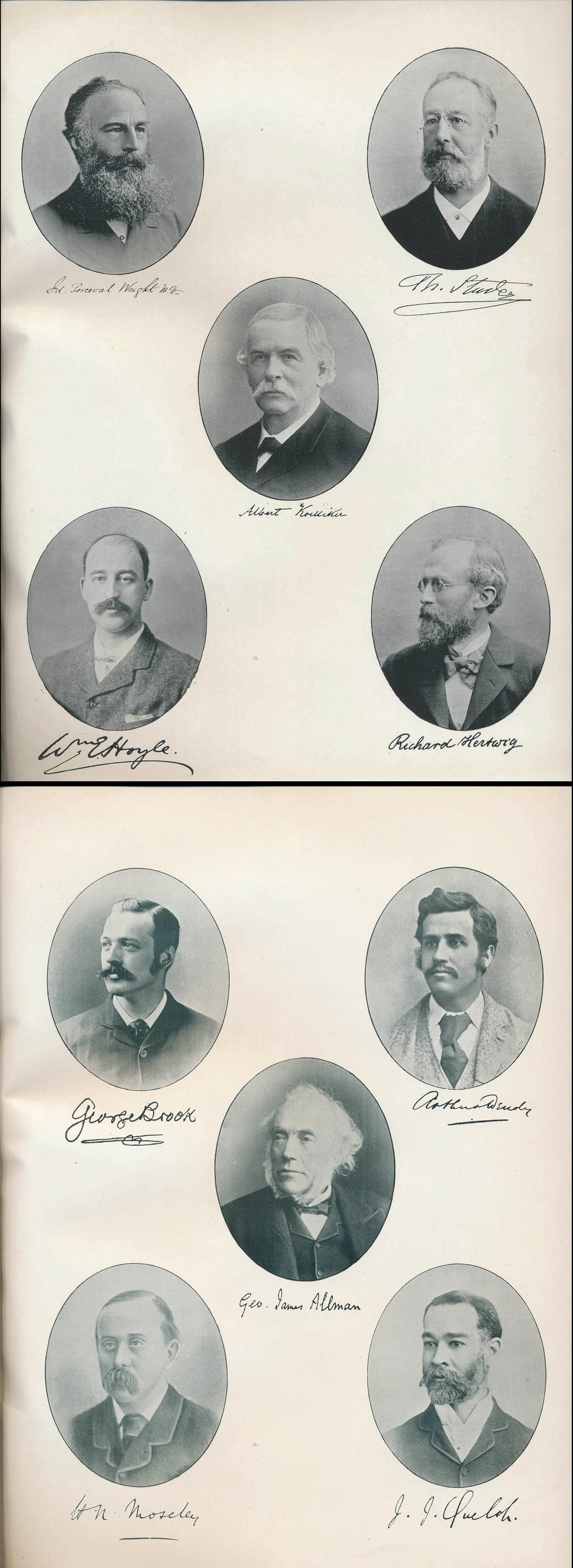

This, however, is not the end of the story. On her voyage, the Challenger measured depth and temperature and collected biota, samples of living organisms from the sea floor, at 360 stations along the route of her voyage. The vessel was fitted with a fully-equipped laboratory, and vast volumes of specimens, data, and readings were amassed during the three years at sea; sediment samples sealed in meticulously-labelled bottles and countless specimens steeped in alcohol, volumes upon volumes of log-books and charts, water samples, and photographic negatives. There is a limit to the amount of useful scientific study that can be done by half-a-dozen scientists on a ship, so the massed volume of potential information was stored for the journey before being distributed across the country upon the ship’s return, each major grouping of specimens going to an organisation or individual most proficient in the study of that given group. Thus began the process of documentation, interpretation, and publication which follows any respectable scientific endeavour; but from the start it was fraught with difficulty, and the project would outstrip the length of the voyage six fold in terms of years spent upon it.

Tome after tome…

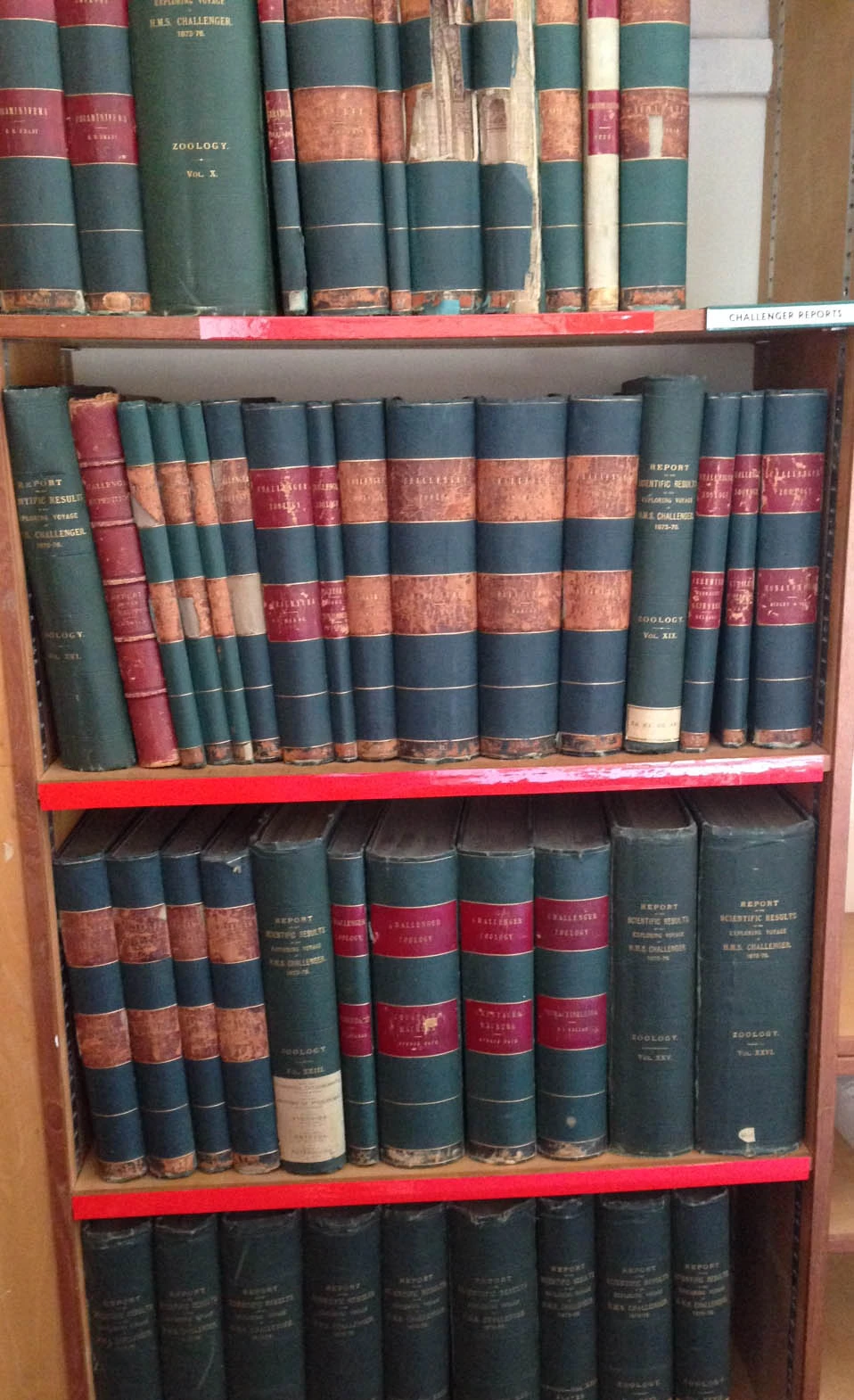

The grandly-titled ‘Report of the Scientific Results of the Voyage of H.M.S. Challenger during the Years 1873-76’, and its associated texts, started trickling from the presses almost as soon as the ship returned to port, but publication would drag on across fifty volumes and more than 29,500 pages. These shelves of heavy tomes contained the distilled data of the expedition, beautifully illustrated with hand-coloured lithographs depicting the litany of species which described as new to science. Wyville Thomson oversaw the publications, but the stress of the project overwhelmed him and he withdrew in 1881, dying shortly afterwards. His place was taken by John Murray, his friend and fellow oceanographer on the voyage; the Report would not be completed until nineteen years after the Challenger docked, a vast, sprawling and prohibitively expensive manuscript which has yet to be matched in terms of vision, boldness and scope (and quite possibly cost) to this day. In the current climate of meandering austerity and profit-motivated science, it seems inconceivable that such a dedicated blue-skies expedition, and the years of follow-up, could be mounted in the 21st century; modern oceanography exists as a passenger, travelling alongside the oil industry and the world’s navies, everywhere studying the workings of nature through the lens of humanity’s impact upon it.

Echoes of Challenger

Echoes of Challenger appear everywhere in the study of samples from the deep ocean. Besides the heavy, leather-bound volumes that sit in the Mollusca Library at the Museum, the Ted Phorson collection which I’m currently working on contains swathes of sub-millimetre-sized mollusc shells (and other, stranger things) sampled from the North Atlantic by a remote vehicle (R.V.) designated vessel named Challenger, and Phorson himself worked on some of Charles Wyville Thomson’s still-unsorted specimens in the late 1970s, almost a hundred years on from when they were first collected. Modern scientific literature on the fauna of the deep oceans refers frequently to the Challenger Report, as so few works have tackled these organisms at the same level of detail since, and it seems unlikely that the oceanographers of the future will be able to; the days of the explorers are surely long gone. It is easy to feel a twinge of nostalgia for the scientific buccaneers of Challenger and, before it, the Beagle voyage – free from want for time and money, invested not with a desire for the wealth of nature, nor with a noble wish to save the oceans from man’s depredations, but instead willing to cast themselves out into the boundless wastes of the sea in search of the heady drug of knowledge, a pure and stupefying substance that raises one above the clouds, denied to us pragmatic, modern mortals. It is comforting to think of the vast mines of secrets that remain undreamt amid the vastness of the abyss, waiting for the explorers of the far future to uncover. Perhaps it is just as well that the days of the old sojourners are over, for now – after all, they have left the better part of their work undone.