Nature Finds a Way

3 May 2022

The Recolonisation of Invertebrates on Restored Grassland:

I’m Alyson, a Professional Training Year placement year student from Cardiff University (School of Biosciences), currently working within the Entomology department at National Museum Cardiff under the supervision of Dr Michael R Wilson (researchgate.net). My interest in ecology, conservation and zoology ultimately led me here, and with no prior specialist knowledge in entomology (the study of insects) I jumped in at the deep end. Within a few months I was sampling in the field and identifying leaf- and planthopper species from Ffos-y-Fran (an open cast colliery site near Merthyr Tydfil). This is currently undergoing the process of restoration so that it is converted from a colliery site to reseeded grassland.

Sampling in the field at Ffos-y-Fran in July 2021

Samples were then frozen and analysed along with samples taken in 2017-2019

Sorting invertebrate samples using a microscope and forceps into labelled tubes of ‘Hemiptera’, ‘Coleoptera’, ‘Diptera’ and ‘Assorted’ before storing specimens in 80% alcohol for preservation

Identifying and analysing over four years of invertebrate samples, involved looking at 195 samples. This took a fair amount of time but allows the rate of recolonisation over a 5-year period, total species diversity, richness, and population dynamics within the fields across the years and seasons to be calculated. Leaf- and planthoppers (Hemiptera: Auchenorrhyncha) were chosen as models within this study as they are frequently common within grassland environments and can be used as an indicator of recolonisation progress on man-restored environments and ex-colliery spoil sites. Colliery sites are a common landscape visible across the UK, especially in the south Wales valleys. Their ecological importance and possible biodiversity are often overlooked, however work by Liam Olds (formerly Natural Talent apprentice at Amgueddfa Cymru), continues to highlight this through the Colliery Spoil Biodiversity Initiative (https://www.collieryspoil.com/about).

The 195 samples were sorted into tubes labelled as ‘Hemiptera’, ‘Coleoptera’, ‘Diptera’ and ‘Assorted’

Further sorting of the Hemiptera samples to species level in order to record population and gender numbers

I am currently in the process of analysing this huge data set and creating a report to show the findings. However, in summary, the data has shown a trend of increasing diversity of hopper species within the field since it was reseeded. In total, 33 species were identified from the site – highlighting the ecological importance these habitats hold. Interestingly, grassland species generally uncommon to the area such as the planthopper Xanthodelphax flaveola and the leafhopper Anoscopus histrionicus, were abundant across the site leading to interesting discussion points as to why this environment encourages their colonisation. Other observations and discussions have also arisen from different wing-morphologies (shapes) seen in specimens of the same species. For example, the discovery of long-winged females of Doratura impudica, which are commonly a brachypterous species (short or rudimentary wings) encourages thought on arrival and colonisation methods of certain species, which could potentially help analyse other environments under recolonisation and ‘rewilding’ programmes.

Uncommon species of grasslands in the area, leafhopper Anoscopus histrionicus (male specimen) were observed frequently at Ffos-y-Fran.

Uncommon species of grasslands in the area, planthopper Xanthodelphax flaveola (male specimen) were observed frequently at Ffos-y-Fran.

Long-winged morphs of Doratura impudica, a brachypterous species (short or rudimentary wings), were observed infrequently across the site

Studying the recolonisation of hoppers at Ffos-y-Fran has allowed me to develop and gain numerous skills which I will take with me into my final year of university and beyond. Not only have I been able to improve on existing skills such as report writing and data analysis, but I’ve also had the opportunity to gain new skills such as invertebrate identification, mounting specimens and taxonomical drawing. I’ve also had the chance to use the Scanning Electron Microscopy and sputter coating, and I have also used the imaging equipment at National Museum Cardiff to create a ‘species guide’ of the 33 observed at Ffos-y-Fran to supplement the report and provide a visual aid. Within my first few months at the museum, I was also able to get involved in a data collection project run by Dr Alan Stewart (University of Sussex), analysing specimens within the Auchenorrhyncha collections to create spreadsheets for the eventual creation of species distribution maps as part of the UK Mapping scheme for this insect group. There are so many opportunities and experiences to be had within the museum!

Looking through the collections and understanding the role of a collections manager

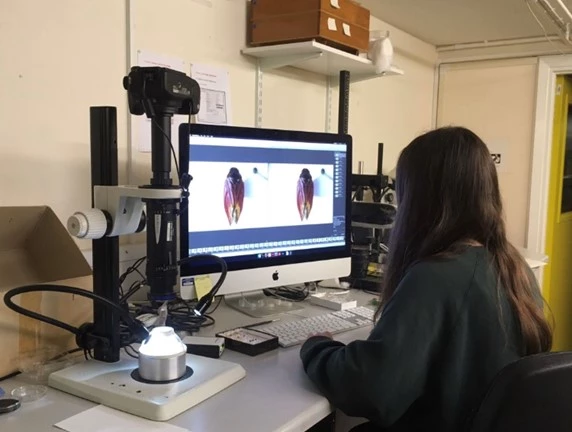

Gaining experience in imaging by photographing Fijian spittlebugs in preparation of redescribing and describing new species

My time with Amgueddfa Cymru has been amazing, conducting research and joining the Natural Sciences team, and has solidified my desire to pursue a career in research. I believe my placement has given me a great start for a future career with the skills I’ve gained and developed through my work on Ffos-y-Fran and my secondary research project. The second project I am currently working on in collaboration with Dr Mike Wilson will provide an up-to-date redescription and description of new species of Fijian spittlebugs with the aim of publication of my first peer-reviewed scientific paper. Watch this space to find out more on the latter project ….