A new Welsh treasure trove of very special fossils

, 1 May 2023

Amgueddfa Cymru – Museum Wales palaeontologists have discovered a large number of extraordinary new fossils, including many soft-bodied creatures, at a new site in mid Wales. Honorary Research Fellows, Dr Joe Botting and Dr Lucy Muir, are working with Senior Palaeontology Curator Dr Lucy McCobb and colleagues from Cambridge (Dr Stephen Pates), Sweden (Elise Wallet and Sebastian Willman) and China (Junye Ma and Yuandong Zhang) to study the fossils, which feature in a paper just published in Nature Ecology and Evolution. Independent researchers Joe and Lucy discovered the new fossil site, known as Castle Bank, near their home in Llandrindod Wells during Covid-19 lockdown. Unable to travel to use museum equipment, they crowd-funded to buy special microscopes to allow them to study their finds in more detail. Ongoing work on the fossils is revealing a much more detailed picture of life in ancient Wales’ seas.

Where are the fossils from?

The fossils were discovered in a quarry on private land not far from Llandrindod Wells (the exact location is being kept secret to protect the site). The rocks in which the fossils were found were laid down under the sea during the Ordovician period, over 460 million years ago, a time when what is now mid Wales was covered by an ocean, with a few volcanic islands here and there.

What kinds of animals were found at Castle Bank?

Fossils of lots of different kinds of animals were found at Castle Bank, totalling over 170 species so far. Most of the animals were small (1-5 mm) and many were either completely soft-bodied when alive or had a tough skin or exoskeleton. Places where soft-bodied fossils are found are very rare. They give us an important glimpse of the full variety of life in the past, not just the animals with hard shells and bones that are usually found as fossils.

The soft-bodied fossils include lots of different worms, some living in tubes. There are also two kinds of barnacle, two different starfish and a primitive ‘horseshoe crab’. Our own branch of the family tree is also present, in the form of primitive jawless ‘fish’ called conodonts.

Castle Bank fossils include the youngest known examples of some unusual groups of animals, including ‘opabiniids’ with their vacuum cleaner-like proboscis [Unusual new fossils from ancient rocks in Wales | Museum Wales]. There is also a ‘wiwaxiid’, a strange oval-shaped mollusc with a soft underbelly and a back covered with rows of leaf-shaped scales and long spines. Another animal resembles Yohoia, an arthropod with a pair of large arms out the front, tipped with long spines for grasping food. Before the Castle Bank discovery, these kinds of animals were only known from much older rocks, dating from the Cambrian period over 40 million years earlier.

On the other hand, some Castle Bank fossils appear to be the earliest examples of their kinds yet known. If what looks like a horseshoe shrimp really is one, then it is the first fossil ever found of a group of crustaceans only previously known from living examples. And another fossil looks remarkably like an insect and may be distantly related to these familiar creatures, which didn’t appear (on dry land) until 50 million years later.

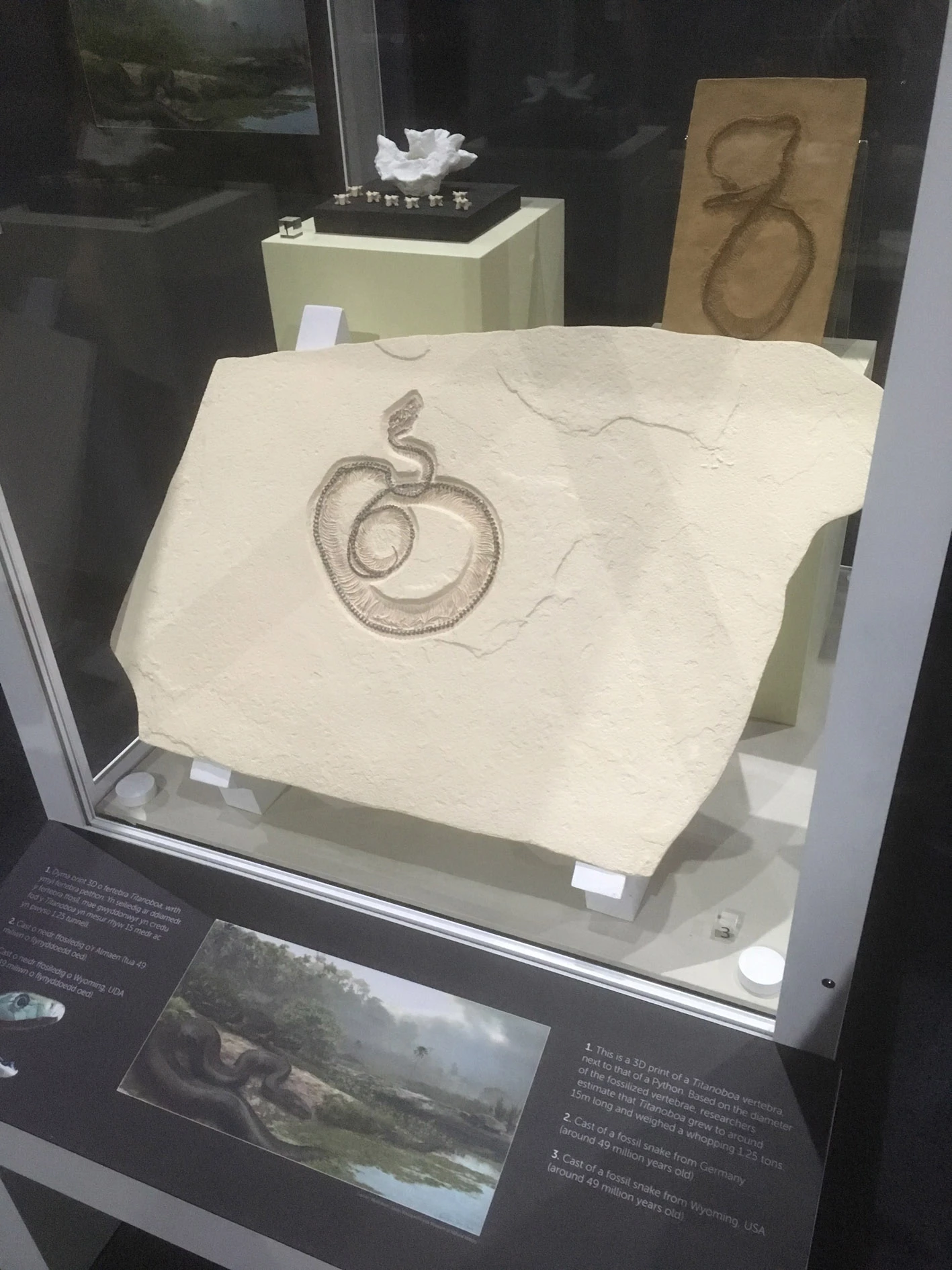

Most Castle Bank fossils are found as dark shapes on the surface of the rock, a type of preservation known as ‘Burgess Shale-type’ where soft tissues are fossilised as films of carbon. Almost all the previous examples are from the Cambrian Period (when animals with skeletons appeared in the fossil record), but Castle Bank dates from the Middle Ordovician, some 50 million years later. This is important, because it gives us a new window into how life was evolving at this time.

Very fine details of the fossils can often be seen under the microscope. A pair of eyes and the outline of what may be a primitive brain are visible in the head of an unknown arthropod. Several trilobites have traces of their guts inside, and some of the worms have tentacles and jaws. Only one other Ordovician site in the world (the Fezouata Biota of Morocco) preserves close to this level of detail.

Researchers in Sweden also dissolved some of the rock in hydrofluoric acid, which left behind minute fragments of organic remains. Under the microscope, these show cellular-level detail and provide clues to an even greater diversity of life than can be seen with the naked eye.

Future research on these intriguing fossils aims to unravel more of their secrets and to figure out their exact relationships to the rest of the tree of life.

What was life like at Castle Bank 460 million years ago?

All animal life was under the sea at that time. A lot of the Castle Bank animals fed by filter feeding (filtering small particles of food out of the water) including a huge variety of sponges, along with sea mats (bryozoans), shellfish known as brachiopods and colonies of graptolites. Many of these may have lived attached to underwater rocks and provided shelter for other animals that moved around.

Most of the animals living at Castle Bank were small (1-5 mm). They include lots of juveniles of a common trilobite called Ogyginus (but no adults), which suggests that this was their nursery, with fully grown trilobites living elsewhere. Many other animals appear to be adults of small species. Perhaps Castle Bank was a relatively safe, sheltered place, where smaller creatures lived in nooks and crannies away from the more perilous open ocean.

Joe and Lucy are still collecting fossils at Castle Bank as often as they can. Many more new species are likely to be discovered in the coming years, as the rocks gradually give up their secrets. We’re looking forward to learning much more about life in ancient Wales.

What can I do if I find an unusual-looking fossil?

As these fossils show, there are still lots of exciting new things to discover in Wales. If you find something that looks interesting and you're not sure what it is, our Amgueddfa Cymru scientists would be happy to try to identify it for you, whether it's a fossil, rock, mineral, animal or plant. Just send us a photo (with a coin or ruler included for scale) with details of where you found it. You can contact us via our website (https://museum.wales/enquiries/) or on Twitter @CardiffCurator We also have a number of spotters’ guides on our website, which will help you identify a lot of the more common things you’re likely to come across (https://museum.wales/collections/on-your-doorstep/identifying-nature/spotters-guide/)

Glossary:

Arthropod = an animal with no spine, a hard outer shell (‘exoskeleton’) and lots of jointed limbs. Includes insects, spiders, crabs and scorpions.

Mollusc = an animal with no spine and a soft body, often partly covered by a hard shell. Includes slugs, snails, clams and octopuses.

Crustacean = an arthropod with a hard outer shell, lots of legs and two antennae (‘feelers’). Includes crabs, lobsters, shrimps and woodlice.

Bryozoans = tiny animals with no spine that live together in branching, rounded or flat colonies in the sea and filter food particles out of the water. Also known as sea mats or moss animals.

Brachiopod = shellfish with two shells and a special feeding loop covered with tentacles and fine hairs for filtering food particles out of the water. Also known as lamp shells.

Graptolites = tiny extinct animals with no spine that lived together in branching tube-like colonies with cups to house individuals, which filtered food particles out the water. Lived on the sea bed or floating in the water.