Dust. Anybody? No? Dust. Anybody? No.

, 13 July 2016

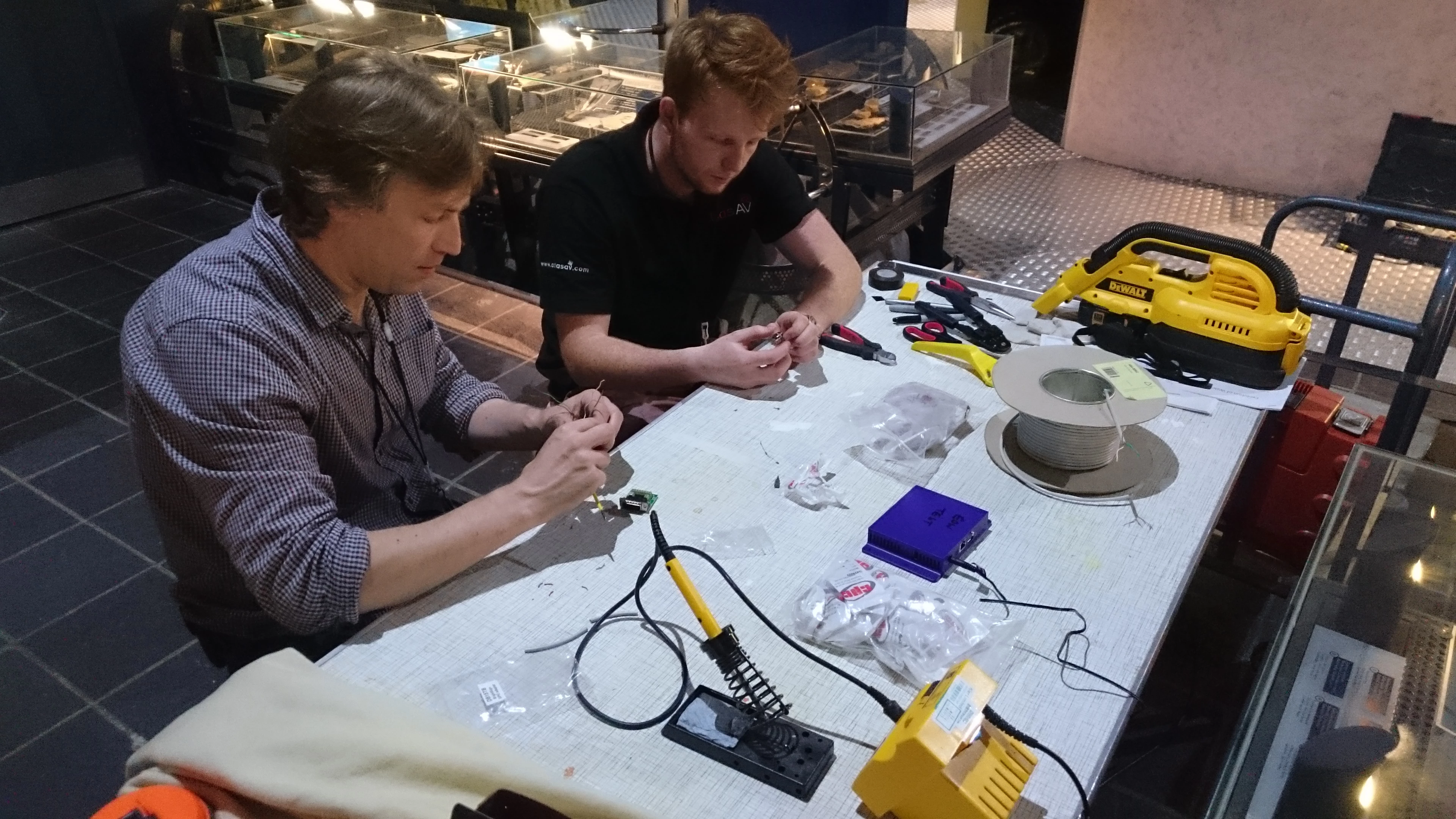

Keen-eyed visitors to National Museum Cardiff may have noticed recently the presence of little pieces of black card in some of the galleries. These pieces of card are there to serve an important purpose: to gather dust. And they are not only in the galleries; we distributed some in collection stores, too.

We want to know just how much dust is building up in parts of the museum. We also want to know what kinds of dust we are dealing with. We can only get this information by monitoring dust deposition.

So what’s the big deal with dust? What harm can a bit of dust do?

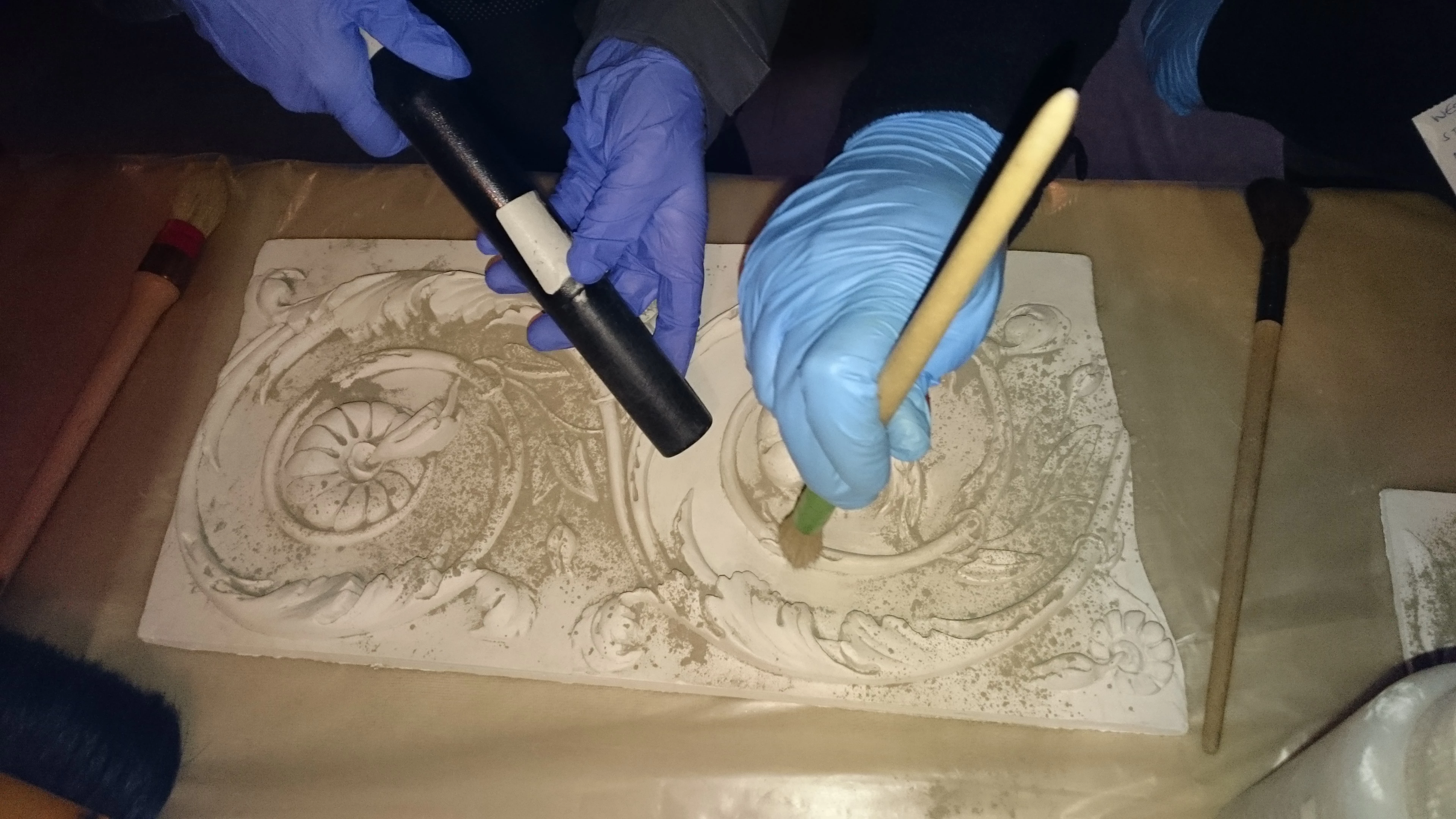

Well dust is unsightly from an aesthetic point of view. In addition, it can actually damage the museum’s collections. When dust sticks to a surface, it really sticks to it. Some types of particles can scratch and mark the surface of objects as they act like an abrasive; this is why when we clean museum objects we are extremely careful not to cause any scratching. Dust also attracts moisture, and surfaces covered in dust are at risk of wicking moisture onto the surface of object which can cause damage. This is especially the case on those horrible rainy days.

So both cleaning the dust and leaving it on risks damaging objects, but by monitoring the dust we can ensure that those risks are kept low and your enjoyment of the exhibits remains high.

Stefan is a student at Cardiff University and currently undertakes research for his MSc in Care of Collections at National Museum Cardiff in conjunction with the Preventive Conservation team.

Find out more about care of collections and Preventive Conservation at Amgueddfa Cymru - National Museum Wales here.