A new mini fossil wonder from near Bala in north Wales

, 3 June 2020

News of a very special new fossil from north Wales was recently published in the scientific journal Royal Society Open Science. I was lucky enough to be involved in the study of the fossil, which was led by Dr Stephen Pates of Harvard University and also included two Museum Honorary Research Fellows, Dr Joe Botting and Dr Lucy Muir. Joe and Lucy found the fossil back in 2012, during fieldwork funded by the National Geographic Society, and donated it to the Museum along with other fascinating fossils from the same site, including various sponges and worms. The fossil was not looked at in any detail until Stephen visited the Museum last year to research other fossils from our collections. His experience told him that it looked like something unusual, so we decided to investigate further. We studied it under the microscope and took detailed photographs, which were then compared with fossils from other places. It turned out to be not only an animal previously unknown to science, but the first of its kind ever to be found in the UK, and probably the smallest known example of its kind.

The new fossil radiodont 'claw'.

Where is the fossil from?

The fossil was found in a block of rock collected from a stream section close to the Arenig Fawr mountain, near Bala in north Wales. You can see a video of Joe collecting fossils at the site here. It comes from the Dol-cy-Afon Formation, rocks that were laid down in the sea around 480 million years ago. What we think of as Wales today, was at that time part of a continent called Avalonia, which was located in the southern hemisphere. The animal was fossilised inside a large burrow, along with remains of other small creatures. We don't know if it was intentionally brought in by the burrow's owner (as a meal perhaps), or if its remains just happened to be present in mud that was pulled in during burrowing.

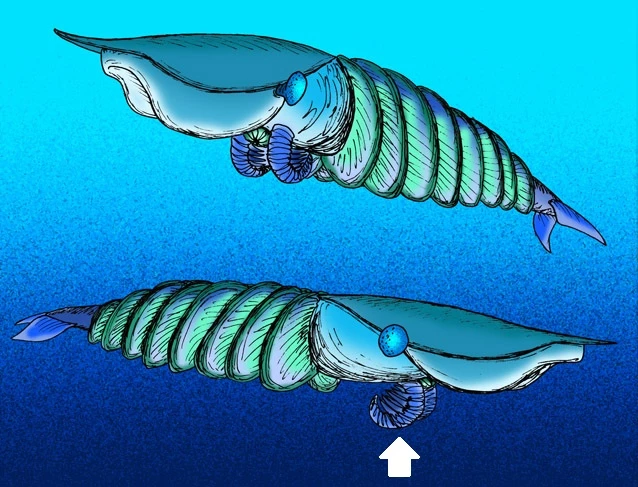

What kind of fossil is it? Reconstruction of Hurdia victoria, a close relative of the new Welsh radiodont from Canada. White arrow points to the 'claws', equivalent to the Welsh fossil. Credit: image adapted from original by Apokryltaros, licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported license.

The fossil is tiny, less than 2mm long. It looks a bit like a comb, with long, thin spines coming off a chunkier shaft. It is actually only part of an animal, a 'claw' used by a creature called a radiodont for feeding with. Radiodonts are relatives of modern-day arthropods such as crabs, insects, spiders and scorpions - segmented animals with hard skins. They were unusual in lacking the jointed legs that their distant cousins scuttle around on. Instead, they had a row of overlapping flaps along the sides of their segmented body, used for swimming rapidly through the ocean. They had large eyes on the end of stalks, one of the features that equipped them to be the earliest known group of large predators to exist on Earth. The new Welsh fossil represents one of a pair of large segmented, spiny claws, which these animals had at the front of their head for capturing food.

Radiodont means 'wheel spoke tooth', a name that reflects their circular mouth, which had a ring of hard, sharp-edged plates that looks a bit like a pineapple ring with razor-sharp teeth. The most famous member of the group is Anomalocaris, first found in Canada's Burgess Shale and thought to have been top predator in the seas over 500 million years ago. If Jaws had been made about the Cambrian Period when it lived, the film might have been called Claws and Anomalocaris would've been the reason not to go back in the water. It is thought to have spied its prey using its large eyes, swooped down and grabbed it with its spiny claws, and then crushed it between the hard plates of its circular mouth.

But while Anomalocaris was a giant for its time, one of the largest animals in existence 500 million years ago at up to half a metre in length, the new Welsh animal was tiny. The whole creature is estimated to have been only around a centimetre long. That makes it the smallest radiodont fossil ever found. We can't tell if it was a fully-grown adult or not, because, as far as we know, juvenile radiodonts looked like their parents.

What did it look like and how did it feed? Reconstruction of Aegirocassis benmoulai, the largest radiodont ever discovered. It lived in Morocco at around the same time as its relative, the new Welsh radiodont. White arrow points to the 'claws', equivalent to the Welsh fossil Credit: image adapted from original by Nobu Tamura, licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International license.

Not all radiodonts were predators like Anomalocaris. Features of their 'claws' provide evidence about how they likely lived. Some had tiny secondary spines coming off the long main spines, creating a network of fine combs that they used for sifting food particles out of mud at the bottom of the sea, or for filtering them out of the water. The Welsh fossil 'claw' has a small number of these secondary spines on it, and it may originally have had these along the full length of the main spines. In any case, its main spines are very close together, which suggests that it was either using them as filters to trap small food particles, or was using them to actively pick up very small items of food.

Although we have only found the fossilised 'claw' of this animal, the bodies of other known radiodonts are all fairly similar, so we can make a good educated guess as to what the rest of it probably looked like. It is likely to have looked similar to one of its closest known relatives, Hurdia, which is known from North America and the Czech Republic. The head was likely covered in a tough carapace with stalked eyes, a mouth underneath consisting of a circle of tooth plates, and the pair of claws attached in front of the mouth to capture and shovel in its food. The segmented body likely narrowed backwards, and had an overlapping row of flaps along its sides for swimming, with gills along its back for breathing. Almost all radiodonts, like the Welsh animal, would have been good swimmers, perhaps spending much of their time skimming along just above the sea bed in search of food. Intriguingly, this tiny Welsh animal is a very similar age to the largest radiodont ever discovered, its relative Aegirocassis from Morocco, which reached two metres in length. By 480 million years ago, radiodonts had clearly adapted to life at both ends of the size scale.

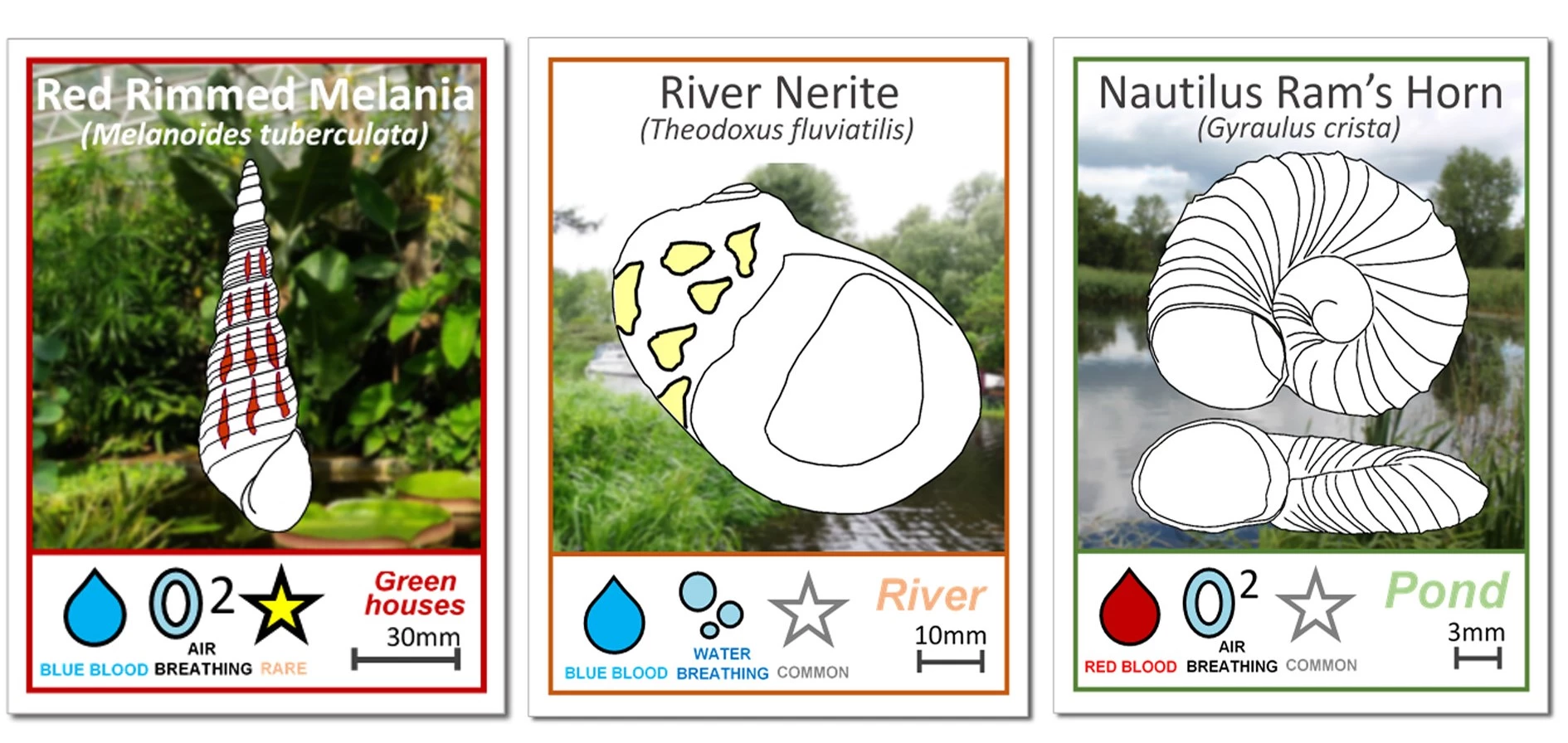

The radiodont shared its home with a huge variety of different sponges. There were also various kinds of worms around, trilobites, shellfish including brachiopods and primitive molluscs, and primitive relatives of starfish.

What can I do if I find an unusual-looking fossil? Reconstruction of Aegirocassis benmoulai, the largest radiodont ever discovered. It lived in Morocco at around the same time as its relative, the new Welsh radiodont. White arrow points to the 'claws', equivalent to the Welsh fossil Credit: image adapted from original by Nobu Tamura, licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International license.

As this fossil shows, there are still lots of exciting new things to discover in Wales. If you find something that looks interesting and you're not sure what it is, our Museum scientists would be happy to try to identify it for you, whether it's a fossil, rock, mineral, animal or plant. Just send us a photo (with a coin or ruler included for scale) with details of where you found it. You can contact us via our website or on Twitter: @CardiffCurator