Polychaetes in the Pandemic

, 11 November 2020

How a Distanced Professional Training Year Can Still Be Enjoyable and Successful

As an undergraduate, studying biosciences at Cardiff University, I am able to undertake a placement training year. Taxonomy, the study of naming, defining, and classifying living things, has always interested me and the opportunity to see behind the scenes of the museum was a chance I did not want to lose. So, when the time came to start applying for placements, the Natural Sciences Department at National Museum Cardiff was my first choice. When I had my first tour around the museum, I knew I had made the right choice to apply to carry out my placement there. It really was the ‘kid in the candy shop’ type of feeling, except the sweets were preserved scientific specimens. If given the time I could spend days looking over every item in the collection and marvelling at them all.

Jars of preserved specimens in the collections at National Museum Cardiff

Jars of preserved specimens in the collections at National Museum Cardiff

Of course, the plans that were set out for my year studying with the museum were made last year and, with the Covid-19 pandemic this has meant that plans had to change! However, everyone has adapted really well and thankfully, a large amount of the work I am doing can be done from home or in zoom meetings when things need to be discussed.

Currently, my work focuses on writing a scientific paper that will be centered on describing and naming a new species of shovel head worm (Magelonidae) from North America. Shovel head worms are a type of marine bristle worm and as the name describes, are found in the sea. They are related to earth worms and leeches. So far, my work has involved researching background information and writing the introduction for the paper. This is very helpful for my own knowledge because when I applied for the placement I didn’t have the slightest clue about what a shovel head worm was but now I can confidently understand what people mean when they talk about chaetigers or lateral pouches!

Part of the research needed for the paper also includes looking closely at species found in the same area as the new species, or at species that are closely related in order to determine that our species is actually new.

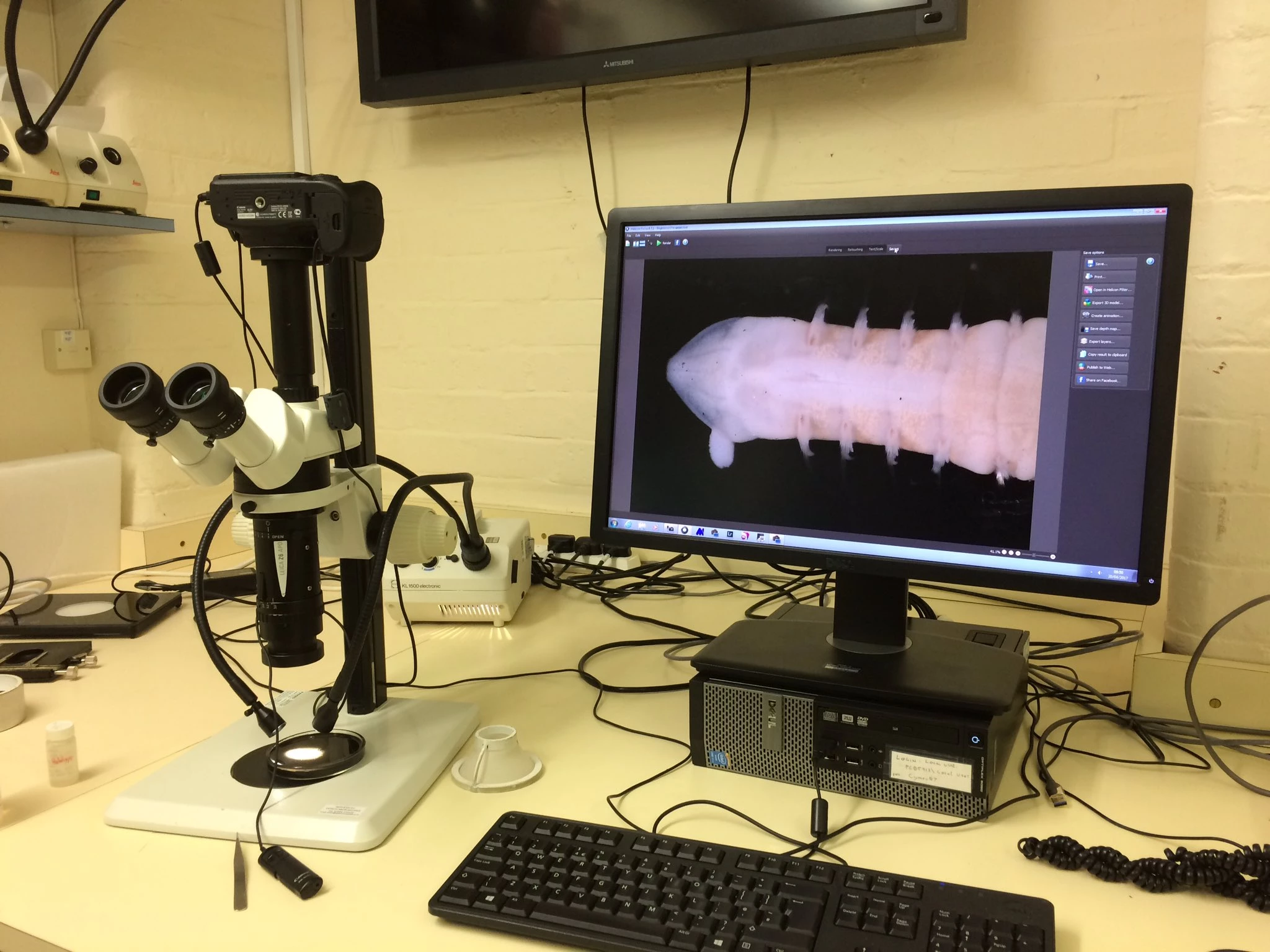

Photos for the paper were taken by attaching a camera to a microscope and using special imaging stacking software which takes several shots at different focus distances and combines them into a fully focused image. While ideally, I would have taken these images myself, I am unable to due to covid restrictions, so my training year supervisor, Katie Mortimer-Jones took them.

Camera mounted on a microscope used to take images of the worms

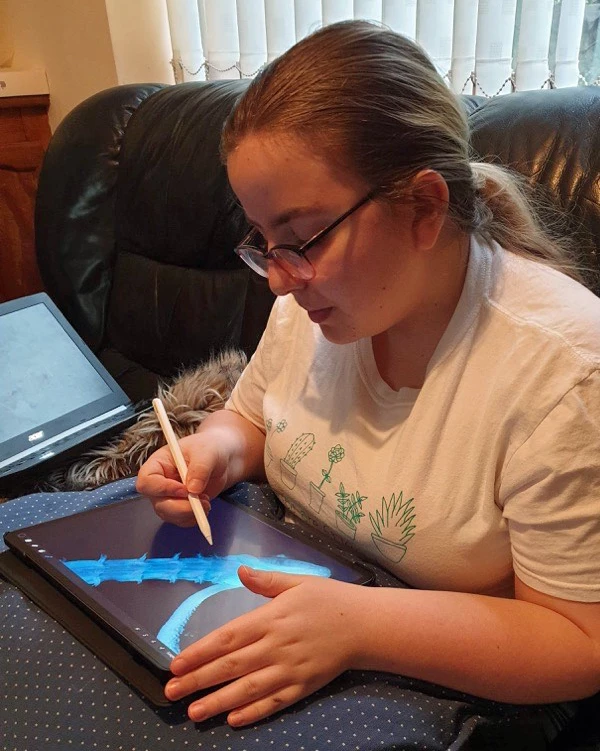

Then I cleaned up the backgrounds and made them into the plates ready for publication. I am very fortunate that I already have experience in using applications similar to photoshop for art and a graphics tablet so it wasn’t too difficult for me to adjust what I already had in order to make these plates. Hopefully soon, I will be able to take these images for myself.

Getting images ready for publication

My very first publication in a scientific journal doesn’t seem that far away and I still have much more time in my placement which makes me very excited to see what the future holds. Of course, none of this would be possible without the wonderful, friendly and helpful museum staff who I have to express my sincere thanks to for allowing me to have this fantastic opportunity to work here, especially my supervisor, Katie Mortimer-Jones.

Shovel head worm