Insect galls in “deep time”

, 7 May 2020

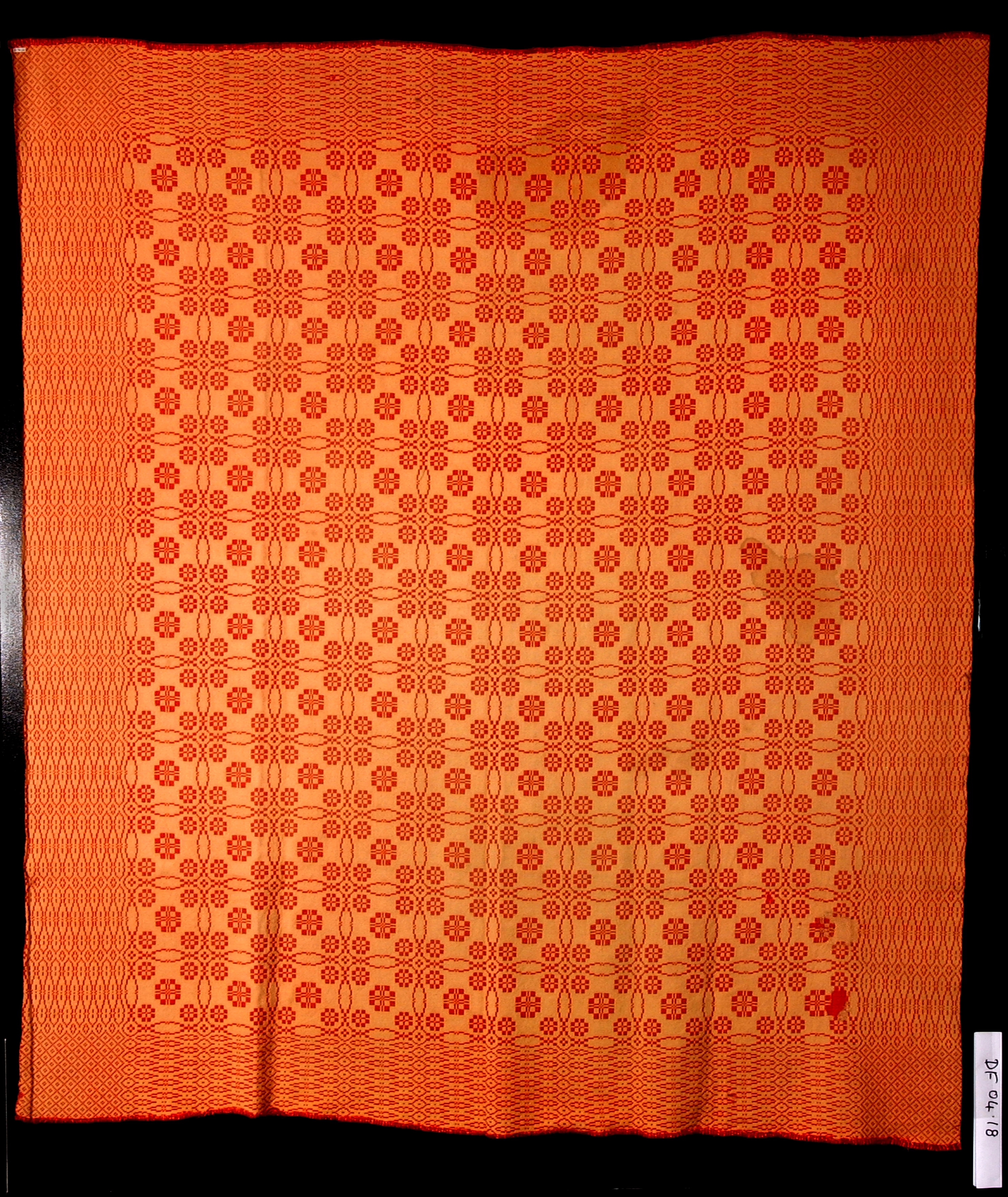

Most gardeners regard horsetails or scouring rushes (Equisetum) as one of their worst enemies – once this invasive weed is in your garden or allotment, it will spread everywhere and is almost impossible to get rid of (Fig. 1). But of course from the plant’s perspective this is a success story – they are doing what is best for them, not for us!

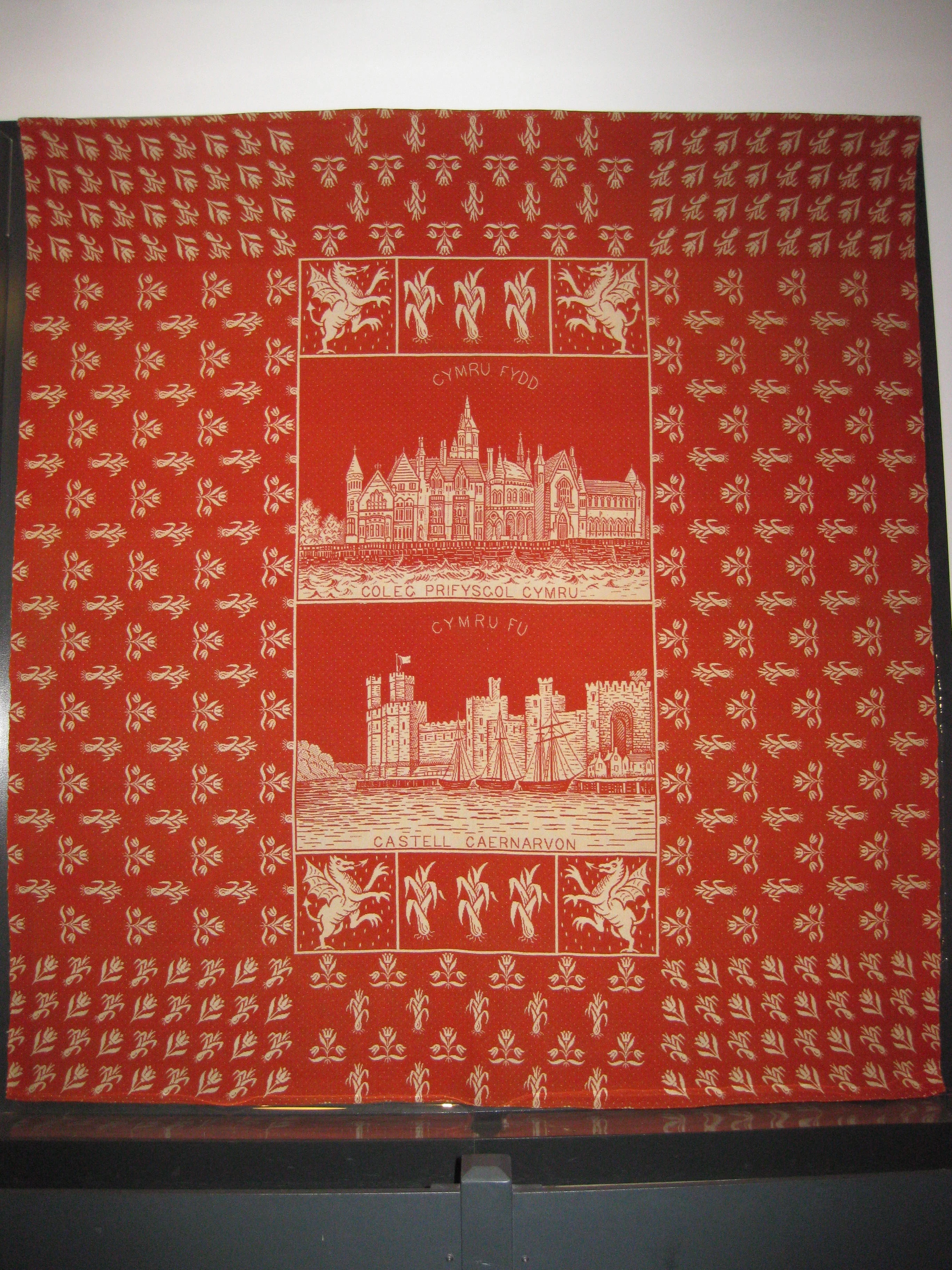

Today, this genus of highly invasive plants consists of only 15 species (Fig. 2), but they are found throughout the world except in Antarctica. They also have an immensely long evolutionary history spanning over 350 million years.

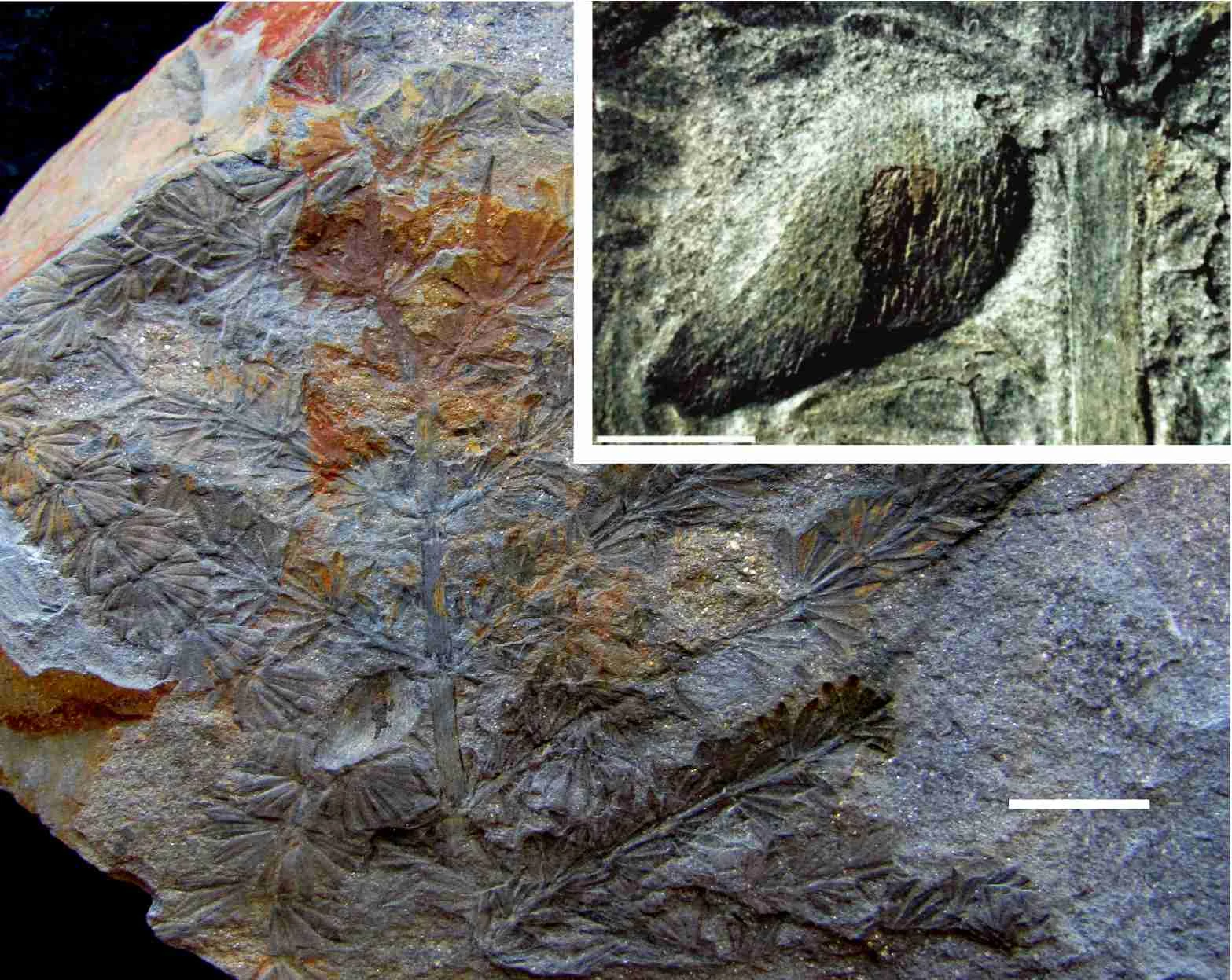

Fossils of horsetails are commonly found in the Carboniferous age coalfields such as in South Wales. The star-shaped leaf whorls (Annularia) are among the iconic fossils found in these rocks. We now know they were parts of tree-sized plants up to 10 metres or more tall – I have often wondered what today’s gardeners would think if they encountered a living one of these giants!

Fig. 3. Fossil horsetail (Annularia paisii) from the uppermost Carboniferous of Portugal, showing insect gall. Insert shows close-up of gall. Specimen in the Museum of Natural History and Science, Porto (UP-MHNFCP-155167).

There is evidence of Annularia leaves having been eaten by insects, such a chew-marks around the leaf edge. Conrad had also published evidence some years ago of an insect gall in a Carboniferous tree fern stem. But a gall on a Carboniferous horsetail is most unusual. For a time we thought this example might be unique. But we then found a paper published back in 1931 by the American palaeobotanist Maxim Elias, who claimed to have found a seed attached to an Annularia. But it is now clear that Elias hadn’t in fact discovered a seed-bearing Annularia, as he had thought, but an insect gall similar to ours.

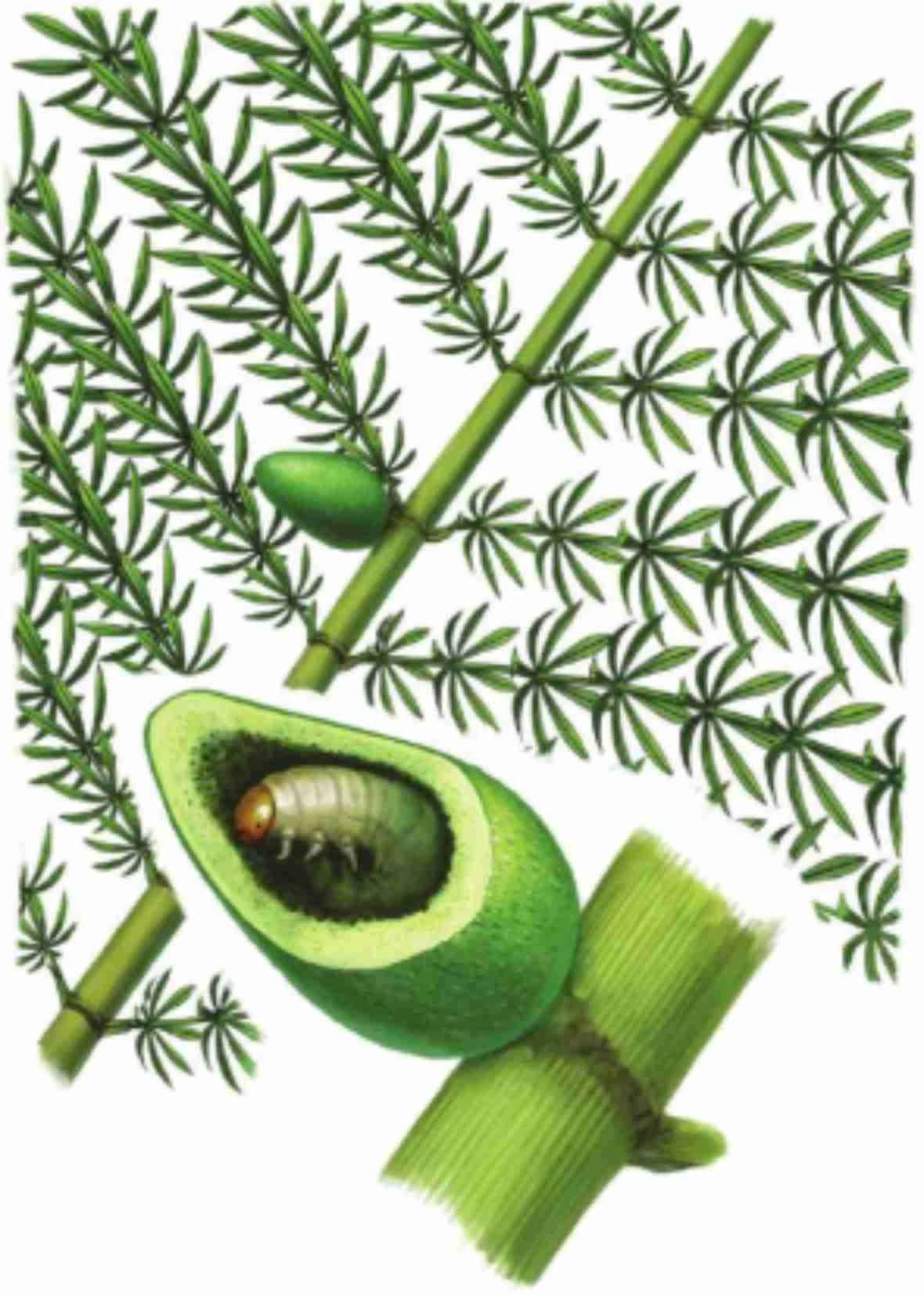

Fossil galls of this age are extremely rare. What insect produced this one is unknown. The organism was not preserved and most of today’s gall-producing insect groups do not have a fossil record extending this far back in time. All that we can say is that it was probably caused by a member of a now-extinct insect group that presumably produced larvae as part of its life cycle (Fig. 4).

Most horsetails have thick, almost leathery stems and I still find it rather strange that insects produce galls on them. But they do today on at least some horsetails, and it has clearly been of benefit to insects for millions of years. We haven’t yet found one in the Welsh coalfields but, now we know what to look out for, we will be keeping our eyes open!

Correia, P., Bashforth, A.R., Šimůnek, Z., Cleal, C.J., Sá, A.A. & Labandeira, C.C. 2020. The history of herbivory on sphenophytes: a new calamitalean with an insect gall from the Upper Pennsylvanian of Portugal and a review of arthropod herbivory on an ancient lineage. International Journal of Plant Sciences, 181(4).