Christmas day is less than a week away and for most of us our tree and decorations are up, Christmas cards posted or messages sent via social media, presents purchased, turkey ordered and Christmas pudding made or bought - these are still popular christmas traditions in 2017 but why do we practice many of these rituals?

Decorations

We have decorated our houses at this time of year since Pagan times. Pagans used evergreens to acknowledge the winter solstice and it reminded them that spring was on it's way. Pope Julius I decided on the 25th of December as the birthday of Jesus, and as this date fell within the Pagan celebrations, some of the Pagan traditions were absorbed into the Christian calendar, including decorating with evergreens and particularly holly. For Christians evergreens came to symbolise God's life everlasting and holly came to represent Jesus's crown of thorns at the Crucifixion, and the berries respresented his blood. Other evergreens also had significance: Ivy as a clinging plant symbolised us holding on to God for support; Rosemary was believed to be the Virgin Mary's favourite plant and laurel represented success and especially God's success in conquering the devil. Holly and ivy were also seen to be representative of a man and woman, holly being prickly and masculine, and trailing ivy being feminine. Whichever was brought into the house first indicated which gender would assume the upper hand for the following year! It was unlucky to bring evergreens indooor's before Christmas Eve and remove them before the 12th night.

In rural Wales homes were usually decorated with evergreens in the early hours of Christmas morning to while away the hours before attending the Plygain service at the parish church, which consisted of an early morning service at somewhere between 3am and 6am and in which soloists and groups sang carols. Candles were also made to light the way to the church and to decorate the inside. Pagans used candles as a decoration to represent the sun and Christians to commemorate the presence of Christ. Before the advent of electricity, candles were used to decorate Christmas trees.

Click here to hear “Parti Fronheulog” and others singing “Addewid rasusol Ein Duw”. Recorded by St Fagans National Museum of History (or the Welsh Folk Museum as it was called at the time) in Llanrhaeadr-ym mochnant Vicarage, following the Plygain Supper held there at the beginning of January 1966.

https://www.peoplescollection.wales/items/738256

Christmas Trees and Other Decorations

There is evidence to suggest that Christmas trees were used as decoration in the U.K. as early as the 1790's and its triangular shape had significance, as it represented the connection between the father, son and holy spirit. Its use became most popular however in Victorian times, when Queen Victoria and Prince Albert used a tree to decorate Windsor Castle in 1841, and in 1848 a picture of the family appeared in the London Illustrated News with a decorated tree.

It was in the early 1920's that evergreens were gradually replaced by artificial decorations, predominantly in the industrial areas, towns and cities. Mass produced decorations became cheaper and more readily available. As early as the 1880's shops such as Woolworths began to sell decorations, sweets cakes and ribbons. It was also during the 1920's and 1930's that Christmas presents began to be wrapped. It was in 1882 that the first electric tree lights appeared in New York, just three years after the introduction of the light bulb.

During the war paper chains became popular as they could be assembled at home and in the 1950's artificial trees became available.

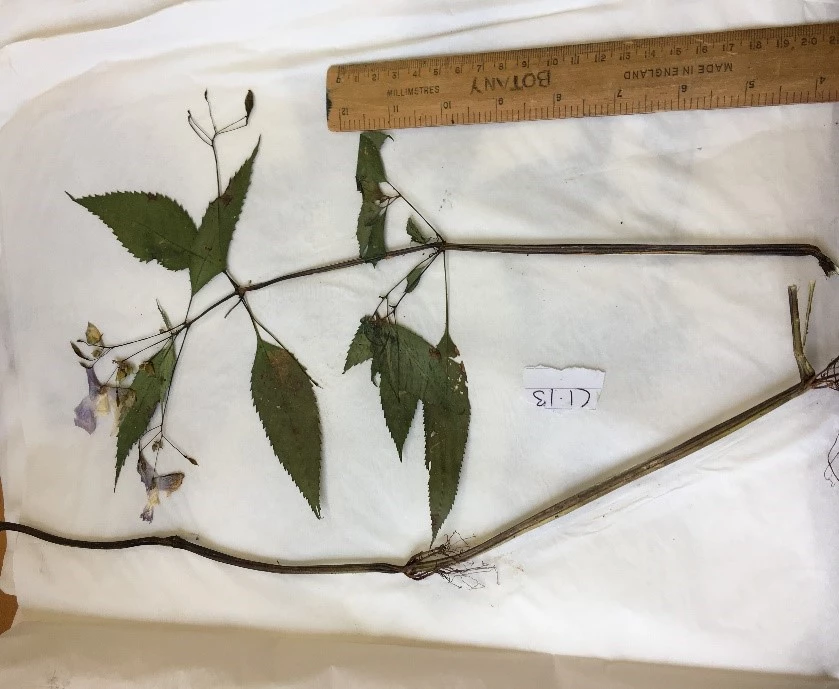

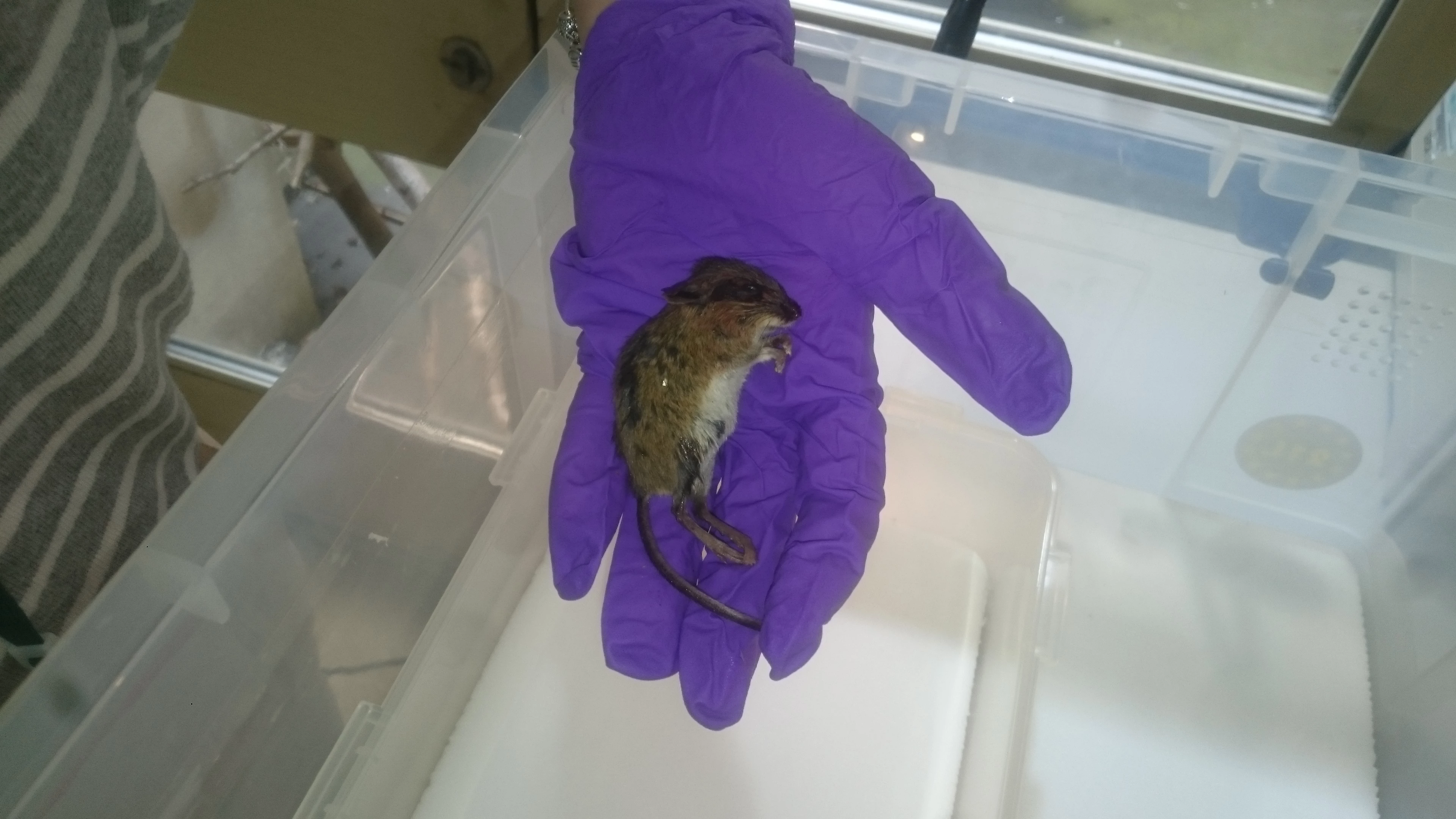

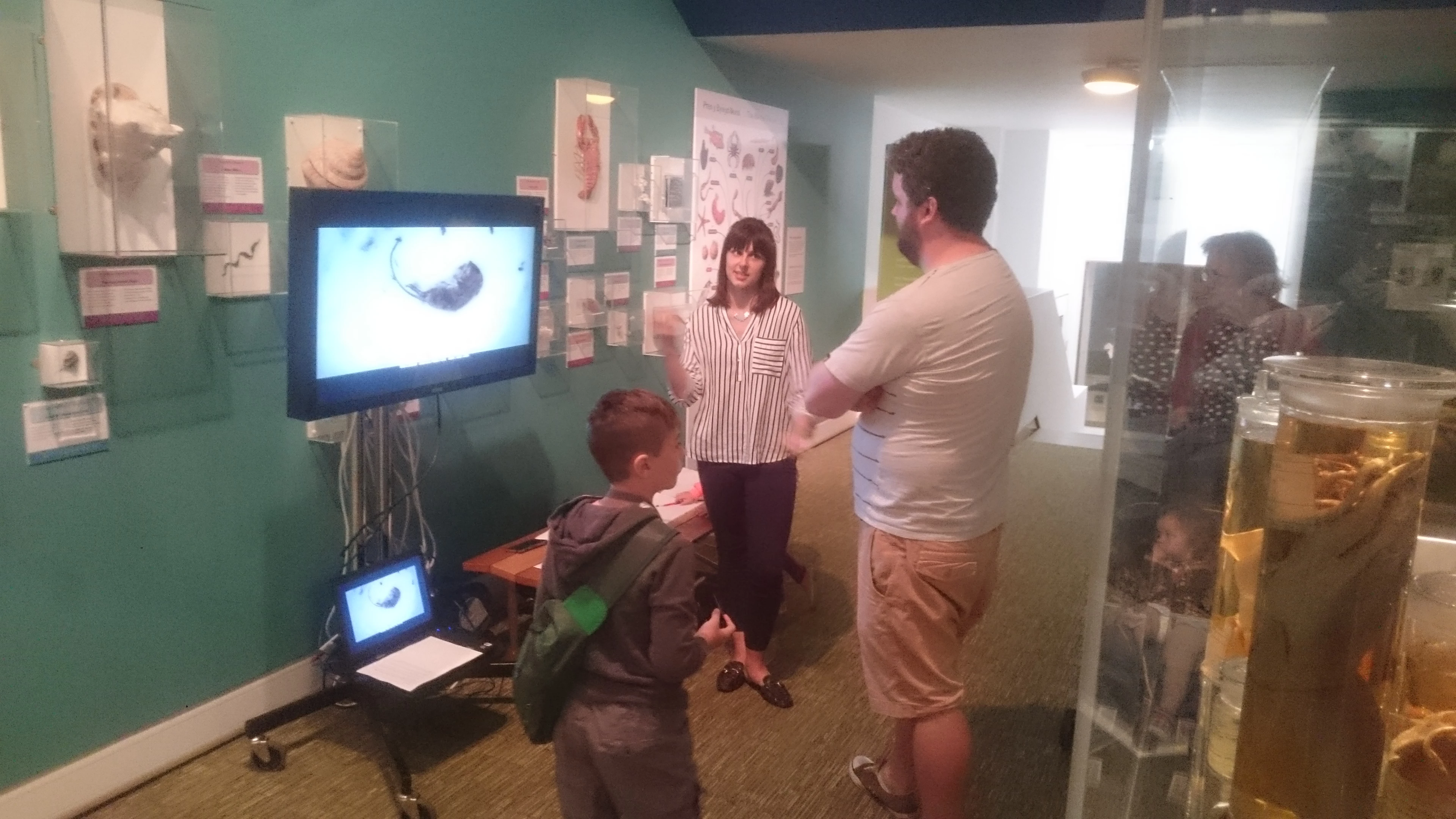

At St Fagans National Museum of History we decorate many of our buildings every year with appropriate decorations according to the age and area of the building. Here are some images.

Although the "Penny Post" was first introduced in 1840 by Rowland Hill, it wasn't until Sir Henry Cole printed a thousand cards for sale at a shilling each in his art shop in London at Christmas time that the idea of sending Chistmas cards emerged as a popular idea. Sending cards became more widespread in 1870 when people could send cards for a halfpenny, as the blossoming of railways made postage cheaper. The Victoria and Albert Museum holds a card sent from Cwrt-yr-Ala in Cardiff in 1844.

Here are some images of Christmas cards from the St Fagans collection

Traditional Christmas Fare

Christmas time wouldn't be complete without the usual over indulgence in rich food. Traditionally the Christmas pudding would be made 5 weeks before Christmas, and in Wales it was customary for all members of the family including children and servants to stir the pudding mixture, often mixed first by the head of the household. In the pudding mixture tokens would be placed such as a a wedding ring; a button; a thimble or a sixpence. If the stirrer found the wedding ring it would foretell the finder's imminent marriage; the finding of a button for a young man would foretell his batchelerhood and the thimble for a young woman an indication of spinsterhood. The sixpence was a symbol of good luck.

Other traditional Welsh foods made at Christmas would be toffee ("cyflaith") made by boiling butter, treacle and sugar to a high temperature and then stretching and rolling the cooling mixture (requiring hard work on the part of the stretcher!). The recipe did vary according to the region. Here's a short film from our archive of this type of toffee being made.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=26bDQqRQICY

Merry Christmas!