Rediscovering First World War collections

, 19 February 2016

Since late 2012, with the centenary of the First World War in mind, curators at St Fagans have been involved in a project to digitise objects with relevance to the conflict. The results are on the First World War database which you can see on this website. But in 2016, the project is still very much ongoing. One aspect which has surprised everyone involved is that objects with stories to tell about the war are still being rediscovered.

Before we began looking specifically for these objects, their potential to reveal stories about the conflict had not always been realised, and connections between objects not always made. Huge numbers of objects were often collected in the past - some in the years immediately following the war - meaning that the information recorded at the time was often limited.

Sometimes a bit of luck has been involved. As part of the Making History project, thousands of items from the collection have moved between storerooms and conservation labs. While auditing an area containing military and civilian uniform, I recently found a collection of badges and buttons of relevance to the period, taking the extent of our First World War collections beyond what we had previously realised.

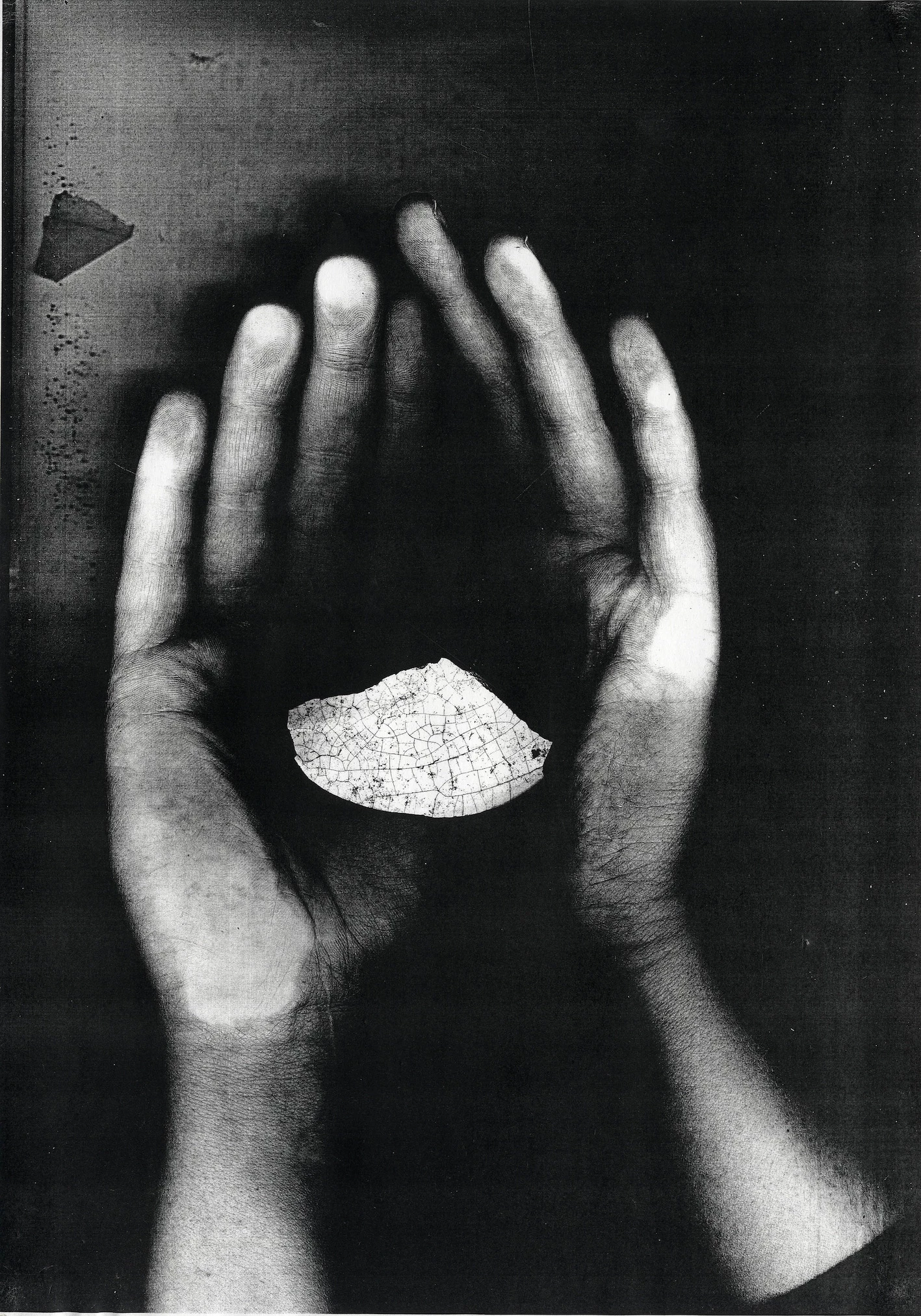

As artefacts of war, these objects often have poignant associations. One lapel badge was recently found complete with a tiny photograph of a soldier who was killed in 1915. A shoulder badge and button of the Grenadier Guards were found belonging to a soldier who was involved in the retreat from Mons in 1914, and of whom there is also a photograph in our collections. We have also discovered objects from areas of the conflict previously thought to be unrepresented in the collections, such as this South Wales Borderers cap badge commemorating the Egyptian campaign.

The exciting aspect of working on this project has been the discovery of collections not previously categorized by their First World War associations. We have uncovered objects in a variety of areas: among pictures and photographs, letters and certificates, medical equipment, textiles, badges and medals. Not only can these items be seen on our First World War database, but some of the stories we have discovered will be told within the displays planned for the new galleries here at St Fagans – just one example of enabling the full richness of our collections to be permanently shared.

This project is supported by the Armed Forces Community Covenant Grant Scheme.